“A London colourman informs me that one Egyptian mummy furnishes sufficient material to satisfy the demands of his customers for seven years. It is perhaps scarcely necessary to add that some samples of the pigment sold as ‘mummy’ are spurious,” writes Arthur Herbert Church in “The Chemistry of Paints and Painting”, published in 1890. The quote references the artist’s pigment made quite literally from the pulverized remains of Egyptian mummies, commonly known as Mummy Brown or “Egyptian Brown”. The practice of producing the mummy-based pigment dates back as early as the late 16th century. Though adored by many artists, the grisly origins of pigment raise the question of what artists are willing to use in the name of beauty.

Mummy medicine

Before it ended up in paints, the powdered remains of mummies were sold in pharmacies. For centuries, “Mumia” was believed to have healing properties. People utilised it as a medicine that was supposed to cure internal bleeding, bruising, or general vitality. But as faith in its medicinal benefits faded, pigment makers found another use for the mummies – this time in art. The transition from apothecary to artist wasn’t a big leap. Embalmed remains were already dark, resinous, and preserved with bitumen and myrrh – materials that happened to lend themselves pretty well to paint-making. All it took was grinding up the flesh, mixing it with asphalt and white pitch, and suddenly, you had a smooth, rich pigment ready for canvas.

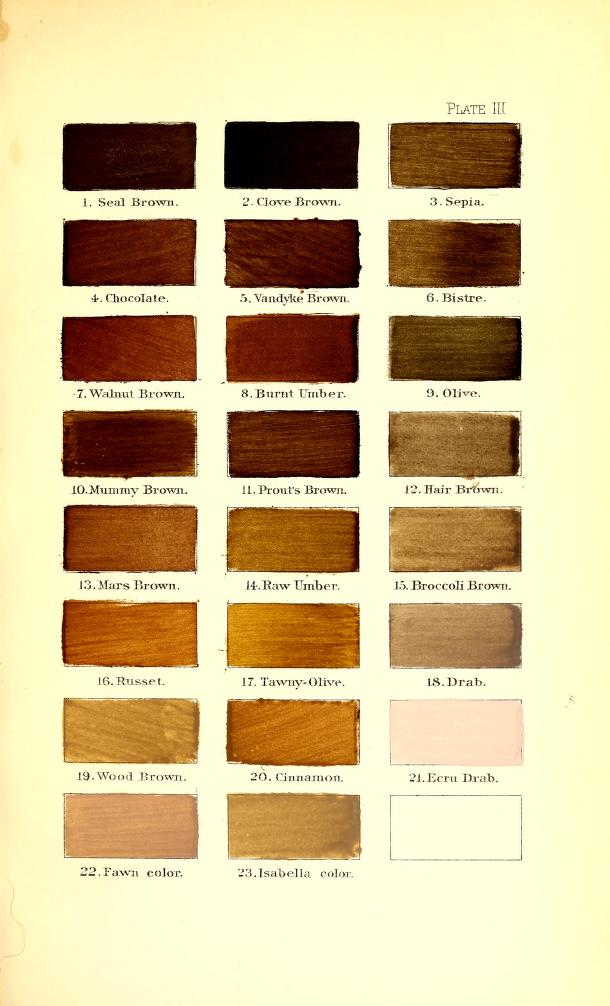

The acquisition process, however, was anything but romantic. During the height of European colonial interest in Egypt, mummies were looted from tombs and grave sites with shocking ease. Some were torn apart for packaging convenience, others were crushed on the spot. Human and animal mummies were reduced to raw materials, stripped of identity and context. The goal wasn’t preservation, but production. Once in Europe, mummies entered the pigment trade through a surprisingly mundane route: through pharmacies. Since apothecaries already sold “Mumia” for medicinal use, it didn’t take long for pigment dealers to tap into the same supply. By the 18th and 19th centuries, Mummy Brown was widely available from London colourmen and pigment houses throughout Europe. As for the pigment itself, it had a distinctive look. Mummy Brown was warm and semi-transparent, falling somewhere between burnt.

Artists liked Mummy Brown for flesh tones, shadows, and glazing effects. It layered well and gave a soft, smoky depth that other browns didn’t. It wasn’t perfect, however, painters eventually noticed that it could fade or crack over time, making it rather unreliable in the long run.

From A Nomenclature of Colors for Naturalists by Robert Ridgway (Boston: Little, 1886), plate 146. Image courtesy of Boston Public Library via Internet Archive Book Images.

Public domain

With its warm, transparent tone and versatility, Mummy Brown didn’t just sit on shop shelves; it found its way into the studios of some of Europe’s best-known painters. From the 18th to the 19th century, it became a staple for artists looking to capture rich shadows, lifelike skin tones, and atmospheric effects. Despite its unsettling source, many painters seemed either unaware of or unbothered by what exactly was in their paint.

Mummy in art. Quite literally

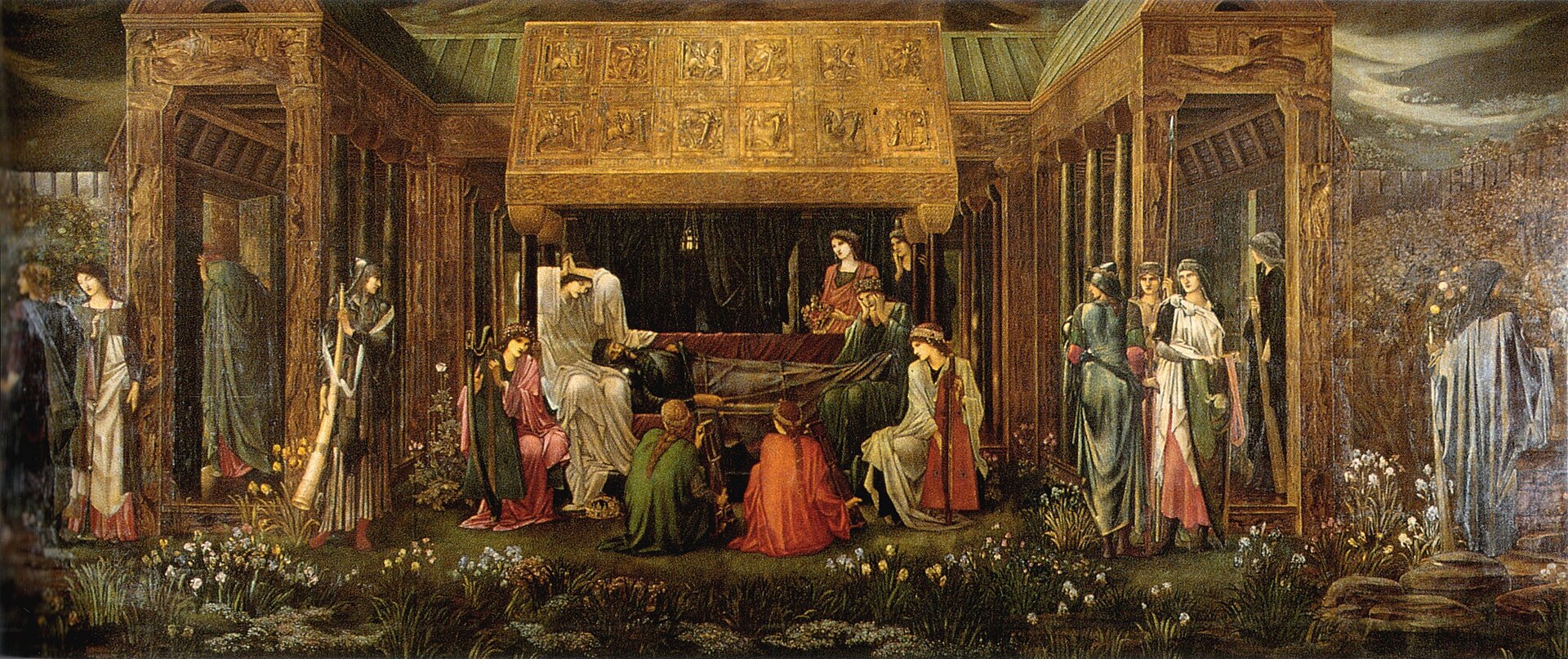

The pigment’s soft, buildable quality made it ideal for glazing and layering, techniques especially favoured by romantic and academic artists. It could add subtle warmth without overwhelming the composition, giving it a distinctive appeal. Eugène Delacroix, for instance, is believed to have used Mummy Brown to add depth and complexity to his scenes. Delacroix was known to have used pigment made from ground mummy, and one of his most iconic works, “Liberty Leading the People”. It’s often cited as a possible example of where the pigment may have been employed to create the rich shadows and warm tones that define the painting’s atmosphere. Similarly, the Pre-Raphaelite painter Edward Burne-Jones used it, at least until he learned where it came from…

Public Domain

That moment of realization is perhaps the most famous turning point in Mummy Brown’s artistic story. Upon discovering that the pigment he had been using was made from actual human remains, Edward Burne-Jones was so horrified that he vowed never to use it again. But it wasn’t just a private reaction: the event became a minor family ritual, and its memory endured.

As recounted by his nephew Rudyard Kipling in “Rudyard Kipling: Something of Myself and Other Autobiographical Writings”, Burne-Jones once descended from his studio holding a tube of Mummy Brown in his hand. He announced to the children of the household that he had learned the pigment was “made of dead Pharaohs,” and declared that they must “bury it accordingly.” What followed was a ceremonial burial in the garden, with Kipling and his cousins assisting. Even years later, Kipling claimed he could still point to the exact patch of earth where that tube was interred. The image is striking: a group of Victorian children helping a Pre-Raphaelite painter ritually lay to rest a pigment made from a long-dead Egyptian body.

The end of Mummy Brown

As odd and theatrical as the moment sounds, it reflects a real shift in how such materials were perceived. The pigment may have come from art shops, but its backstory was increasingly uncomfortable. The burial of a single tube of paint in a garden might seem like a sentimental footnote in the long history of European art, but it also reflected a growing discomfort that would eventually signal the end of Mummy Brown as a pigment. By the late 19th and early 20th centuries, the use of actual human remains, specifically those of ancient Egyptians, was no longer justifiable as romantic or exotic. It had become ethically dubious, even grotesque.

Mummy Brown’s decline wasn’t sudden, but surely it was inevitable. And it wasn’t just the ethics. There were technical issues, too. Though appreciated for its warm tone and transparency, Mummy Brown was chemically unstable: it tended to fade, crack, and age poorly on canvas. As modern pigments improved and artists became more selective in their materials, Mummy Brown’s flaws stood out. Critics, too, began to ask harder questions about what exactly was being bought, sold, and smeared across portraits and religious scenes. Newspapers aimed at the pigment trade, and even colourmen admitted it had become increasingly difficult to source the mummies without attracting outrage. One 1904 advertisement even joked somewhat grimly that surely a 2,000-year-old Pharaoh wouldn’t object to adorning a fresco.

The pigment that had once signified mystery and luxury came to represent the exploitation at the heart of colonial collecting practices. As Egyptian antiquities laws tightened and public sensibilities shifted, the supply of genuine mummies dwindled, bringing the trade in the pigment to an end. Mummy Brown quietly disappeared from most colourmen’s catalogues by the mid-20th century.

By Edward Burne-Jones – Scanned from Christopher Wood, Burne-Jones, Phoenix Illustrated, 1997, ISBN 9780753807279, Public Domain,

Today, Mummy Brown remains a striking example of how art can be implicated in violence and exploitation. It is not just an obsolete pigment, but a historical artifact of colonial greed and moral neglect. In a time when museums face growing calls for repatriation and ethical accountability, the story of Mummy Brown serves as a reminder: beauty, when built on disregard for the dead, carries a legacy that must be reckoned with.

The story of Mummy Brown is a uniquely vivid intersection of art, science, colonial history, and ethics. On the surface, it’s a strange and slightly absurd anecdote: artists once painted masterpieces using crushed-up ancient corpses. But beneath the novelty lies a deeper story about how materials carry meaning, and how the contexts in which we make and use art are never value-neutral.

Mummy Brown’s popularity in Europe wasn’t just about its colour. It spoke to a time when colonial powers felt entitled not only to the lands and labour of other cultures but even to their dead. It reflected a worldview that saw human remains as collectible, commodifiable, and ultimately usable, whether for medical treatment, museum display, or a rich glaze in a portrait. The eventual rejection of Mummy Brown wasn’t just about supply shortages or technical flaws, it was a shift in moral vision. Artists like Burne-Jones weren’t just buying tubes of pigment, they were buying a cultural practice that could no longer be justified.

Today, we have the luxury of recreating such colours synthetically without resorting to desecration. But we also inherit the responsibility of remembering where those colours came from, and what they cost. Mummy Brown is more than a pigment, it’s a story – one that continues to colour how we think about art, ethics, and the legacy of empires.

Bibliography:

Church, A. H. The Chemistry of Paints and Painting. London: Seeley & Co., 1890.

McCouat, Philip. “The Life and Death of Mummy Brown.” Journal of Art in Society.

Kipling, Rudyard. Something of Myself and Other Autobiographical Writings. Cambridge [England]; New York: Cambridge University Press, 1990.

Woodcock, Sally. “Body Colour: The Misuse of Mummy.” The Conservator 20, no. 1 (1996): 87–94. https://doi.org/10.1080/01410096.1996.9995106. 5

About the author:

Anna Mushynska – My academic interests mainly lie at the intersection of art history and archaeology, with a particular focus on the ethical implications of how materials and cultural objects circulate between disciplines. I am also interested in the history of art, especially twentieth-century Ukrainian graphic art and contemporary Ukrainian visual culture. More broadly, I explore the relationship between artistic practice and the artist as a cultural actor.

https://uw.academia.edu/AnnaMushynska