One of the most unexpected and surprising discoveries at Castillo de Huarmey site were the burials dated to the very beginning of the 20th century. They were found within palacio, which is the architectural establishment located at the foot of the hill on which the mausoleum is situated, from which the Castillo de Huarmey is best known. The whole area of this archaeological site functioned as a burial site at least since the Early Horizon (see: Tysiąc lat przed Castillo: Atypowe pochówki z Huarmey ENG!) through the Middle Horizon (these burials were associated with the presence of the Wari Empire in the area), to the Late Horizon. However, discovery of the much younger burials indicate that Castillo functioned as the funeral zone in the minds of even 20th-century residents of the Huarmey Valley. Certainly the hill and overlooking mausoleum, were strongly distinguished in the local landscape (before the great earthquake of 1970 probably it might dominate evenmore so than today), was considered as huaca, which means a “sacred place.” Similar to the platforms of the Moche Valley, or those in the area of modern Lima (e.g. Huaca Pucllana located in Miraflores district).

DISCLAIMER: THIS ARTICLE CONTAINS PHOTOS OF HUMAN REMAINS

© W. Więckowski, under licence CC BY 4.0

The mystery of the funerary archaeology in Huarmey

The excavation conducted in 2017 focused on identifying the courtyard and architecture of the buildings lying south of the Castillo. This area is called a palacio, although it had nothing to do with architecture of a residential character. Rather, it was a complex of buildings of a ceremonial or audience function, whose courtyards were used for public gatherings. During the excavations, the members of the University of Warsaw expedition discovered the burial of the craftsman, who was equipped for his terminal journey with a rich set of woodworking tools, as well as items testifying to his metallurgical skills (mainly copper, of course). This grave can be linked to other burials of artisans discovered in the immediate vicinity of the mausoleum. In the very center of the funerary complex, we encountered the perfectly preserved textiles, and amidst them, a perfectly mummified body. The excitement of the students working on this sector of the excavations was enormous. As the work progressed, more fabrics were uncovered, and it soon became apparent that the mummified corpse were buried in an extended, wrapped in red, coarsely woven cloth. This was strange, since the customary way of burying the dead in the area was a form of so-called fardo, or funerary bundle, in which the body was placed in a seated position.

© W. Więckowski, under license CC BY 4.0

The discussions that arose after this discovery were seemingly endless. These included the debate about the colors and textures of the fabrics. They continued until the area around the mummy’s hand was spotted… the garment’s cuff. The pre-Columbian cloths, which are currently well-studied material-thanks both to the excavations and iconographic representations-did not have sleeves like modern shirts.

It also quickly became clear that the cuff was clipped with … a white button with four holes, shining brightly in the sunlight. It became obvious that we were dealing with a burial, very well mummified and preserved, but completely… contemporary.

A second contemporary burial, albeit badly damaged and in fragments, where some skeletal fragments were wrapped in fabrics and others lay loosely among other pieces of damaged textiles, was discovered nearby during an excavation in the year 2022.

Where do they come from? Who are they?

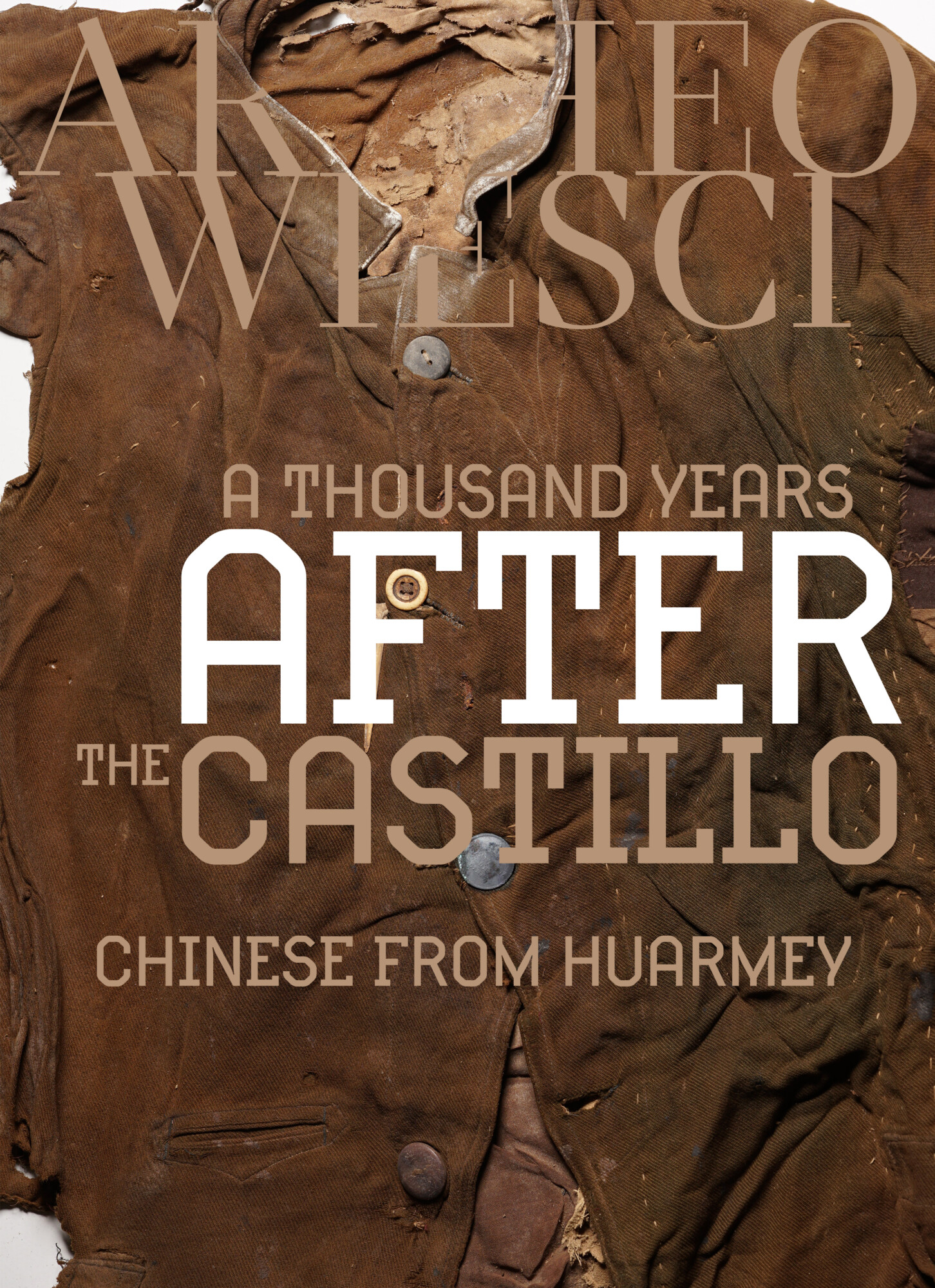

The discussed burial, among which one was perfectly preserved, and the second unfortunately only fragmentary, belonged to representatives of the Chinese diaspora. How do we know that? Most of the soft tissues of the first individual were well-preserved and underwent the process of natural mummification. Thanks to this preservation, the remains had more phenotypic characteristics than skeletonized ones. The final clue was provided by the style of clothes in which the deceased was dressed. First, he wore two shirts with distinctive Chinese-style neck fasteners, then a button-down sweatshirt made of yellowish felt, also with similar hook-and-loop fasteners. On top of that was a green sweatshirt with a collar and spread like a polo shirt. On the very top he also had a green jacket, in which every button was completely different. All the layers of his upper garments were badly worn, and repaired many times. His pants were made of very thin cotton, and on his head was probably a handmade cap. The entire body was wrapped for burial in a red blanket, and a strap of banana leaves was tied under his chin. The feet were wrapped in a flour sack that had been preserved in a large section. The whole thing, therefore, gave the impression of a very poor man who carried everything he owned on and with him.

© W. Więckowski, under license CC BY 4.0

How the burial was dated?

The elements of the grave furnishings allowed us to precisely determine the chronology of the burial. One of the jacket buttons was a military button, with a representation of the crown and engraved „infanteria de linea”. This type of buttons was part of the garment of the Spanish infantry since the beginning of the 19th century. In the middle of the very same century, the soldiers of imperial regiments sent to fight against South American countries fighting for independence had uniforms with these specific buttons. In Peru itself, they may have been in use until the end of the 19th century. Meanwhile, the other interesting button, white and shiny, appeared to be made of… plastic. The buttons made of this material came into fairly widespread use in the 1920s. These early plastic products were made of so-called bakelite (like the dial phones that some older readers may be familiar with). On the other hand, buttons made of celluloid-type plastic were confusingly similar to these later ones. The celluloid could be in use as early as the 1900s.

A fragment of a flour sack with was also interesting. The writing on this contemporary finding announced its origin:

„100 lbs. harina flor del Molino de Otero. Lima”.

Molino de Otero mill functioned in Lima, at the river Rímac since 1739 until 1923, when it was absorbed into the Grandes Molinos del Peru S.A.C. corporation. All the above-mentioned traits indicate that the burial had to take place during the first two decades of the 20th century. In this period, the Chinese migrants brought to work in Peru from the middle of the 19th century, were liberating themselves from slave contracts and seeking happiness and a new life in a new land.

© W. Więckowski, under license CC BY 4.0

A little glimpse of history

In year 1839, Peru was still a young independent republic, as it gained its independence eighteen years earlier in 1821. At the end of the 1830s, Peru abolished the slavery, but it vanished completely no sooner than in 1854, leading to problems in the form of labor shortages, especially in the high-income guano mines, or on the vast cotton and sugar cane plantations abandoned by freed slaves. To prevent the collapse of the economy, Peru decided to invite the workers from China. Between 1849 and 1874, more than 100,000 ventured to South America. They were almost exclusively young men seeking a better life than in their own country plagued by internal unrest and poverty. Unfortunately, they were treated no better than slaves in Peru. In fact, the only difference was the fact that they had a labor contract, which admittedly did not provide them with decent conditions or pay, but had an end date, after which the laborer became a free man. They worked mainly in the agricultural sector, irrigating fields, harvesting, transporting, carrying heavy loads and performing any task requiring physical strength.

© W. Więckowski, under license CC BY 4.0

Working men of Huarmey

The deceased, whose mummified corpse was discovered at the foot of the Castillo de Huarmey, was a middle-aged man who worked very hard physically during his lifetime. This is proven by numerous strongly expressed muscle attachments associated with physical activities of routine scope, involving lifting and carrying. In addition, pathological changes were observed on the lumbar region of his spine, which is often associated with heavy physical exertion, namely spondylolysis and spondylolisthesis.

It means that the vertebral arches of the second through fourth vertebrae were separated from the vertebral bodies, and the vertebral bodies of vertebrae 4 and 5 showed a fairly significant displacement relative to each other. Spondylolisthesis occurs, for example, among athletes or people in jobs that often require excessive physical exertion. It rarely occurs on as many as three vertebrae, much more often on one or two, often on one side. All of this suggests the Far East migrant from Huarmey may indeed have been a laborer at one of the surrounding haciendas.

© W. Więckowski, under license CC BY 4.0

Moreover, the analyses indicate that probably shortly before death, he had his typical Chinese braid cut off. Sometimes this was done because of the adoption of Christianity, and sometimes as punishment for violating some cultural norms. Given that the burial took place on a huaca and not in a Catholic cemetery, we can assume the latter scenario.

The remains discovered in 2022 were similar in many respects to those of 2017. They are analogous to each other due to the similar clothing, and presence of the flour sack with the similar information suggest that we discovered the burial of yet another member of Chinese diaspora in the Huarmey region. His remains are still studied, but it is obvious that his bones also bear witness of the hard labor.

Similar burials are discovered periodically throughout the entire central coast of Peru. Many burials of this type have been discovered at other archaeological sites, in the context of the huacas such as Huaca Mateo Salado or Huaca Bellavista, In addition to that, members of Chinese diaspora were buried also in the vicinity of other archaeological sites, such as Caraballyo, Fortaleza de Pasamayo, on an island that lies facing the mouth of Callao, Peru’s main ocean port, called Isla San Lorenzo.

These isolated burials are testimony of a shameful chapter of Peru’s history. But it has left a lasting imprint on the culture of the country today. Many Peruvians have Chinese roots, and Peruvian cuisine (which wins numerous culinary awards each year) carries a strong influence from Chinese cuisine.

You can read more about the osteobiography and paleopathological study of members of Chinese diaspora, as well as the short introduction into this historical migration in: