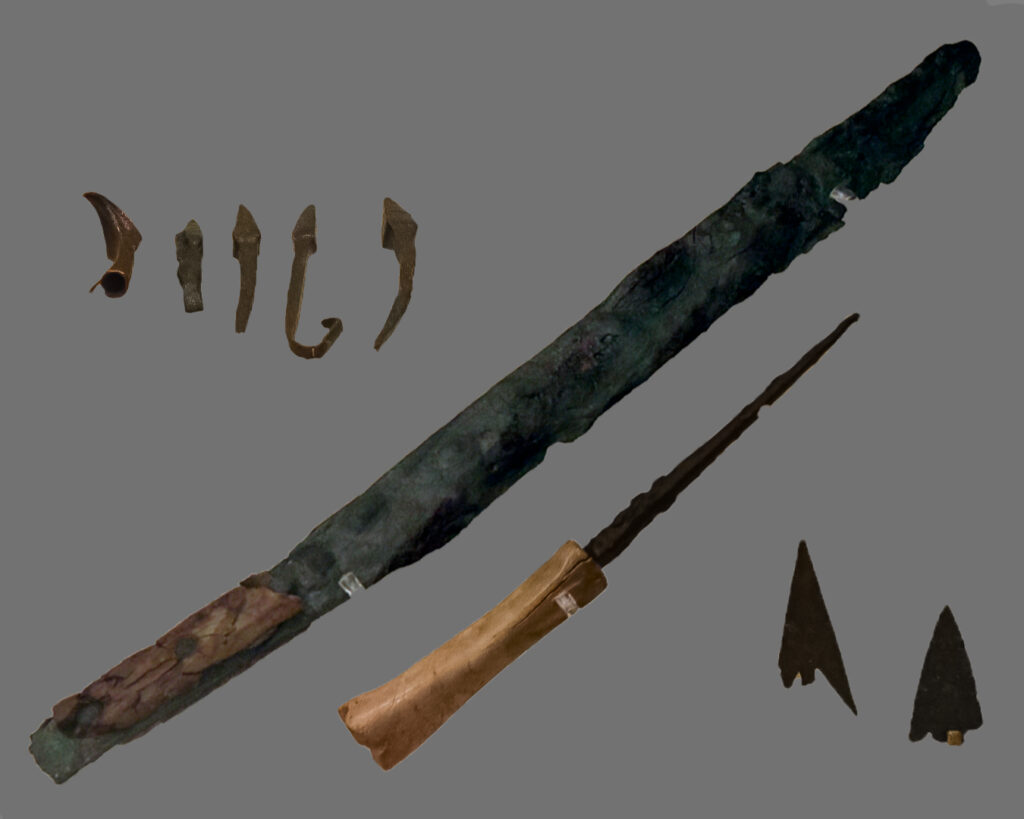

Metal objects from Mycenae are some of the most famous in the archaeological world. Homer memorably described Agamemnon’s Mycenae as “rich in gold”, proven accurate in 1876 when Henrich Schliemann uncovered tombs filled with astonishing gold artefacts, amongst many other valuable treasures.

Trudging through field notes kept in an obscure archaeological notebook for the 1939 archaeological excavations at Mycenae led to an unexpected discovery: a cache of metal artefacts from a rubbish pit near the monumental Treasury of Atreus tomb, the so-called “Atreus bothros”. Yet the objects are unpublished and almost all are missing from the official finds catalogue! What happened to them? The mystery could only be solved by travelling back to 1939…

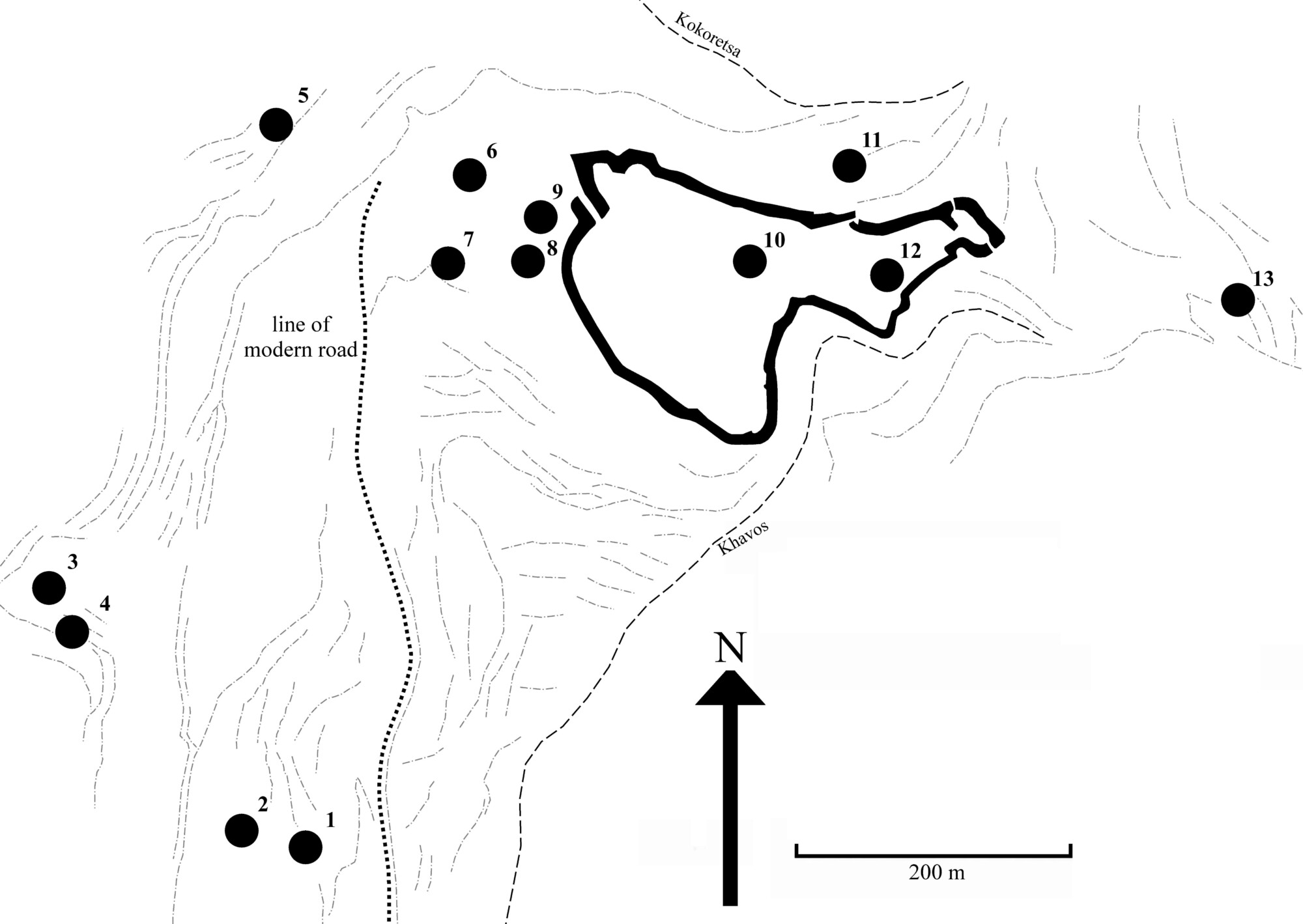

The citadel of Mycenae, situated on a hill overlooking the Argive Plain in southern Greece, is most famous for its Late Bronze Age occupation. This is the period Homer alludes to in his two magnificent epics: the Iliad and the Odyssey.

© S. Aulsebrook, CC BY-SA 4.0 licence

Unsurprisingly, archaeological attention has centred on such finds, with less interest in the everyday use of metals across the whole society. Filling this knowledge gap lies at the heart of the project Forging Society at Late Bronze Age Mycenae: the Relationships between People and Metals, hosted by the University of Warsaw. The project is studying a wide variety of metal artefacts, from lead rivets and bronze tools to gold jewellery and silver cups, building a holistic picture of metal usage at Late Bronze Age Mycenae.

© M. Łapińska/P. Jurkowska, editing S. Aulsebrook, CC BY-SA 4.0 licence

With lockdown preventing fieldwork, research continued by analysing material held online at the Mycenae Archive. This marvellous resource houses digital scans of notebooks, plans, drawings and photographs produced by the Helleno-British excavation team during the 20th century.

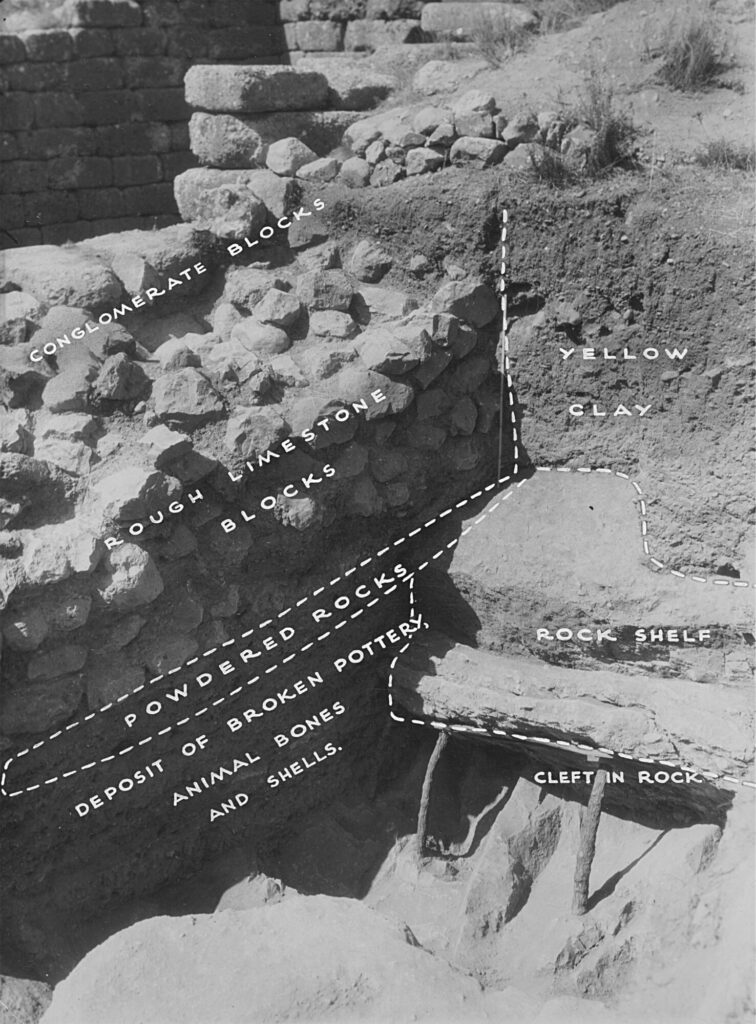

Trawling through field notes for 1939 led to the unexpected discovery of a cache of metal artefacts. These objects had been unearthed from a rubbish pit near the Treasury of Atreus tomb, the so-called “Atreus bothros.” One of the largest non-mortuary collections of metal objects found at Mycenae, it is also the only one found so far that has the potential to shed light on Late Bronze Age metal recycling and discard practices. However, not only were these objects unpublished, they were not even in the official finds catalogue! What happened to them? The search was on for more information, and only by travelling back to 1939 could this enigma be unravelled.

Image courtesy of the Mycenae Archive

The 1939 Dig

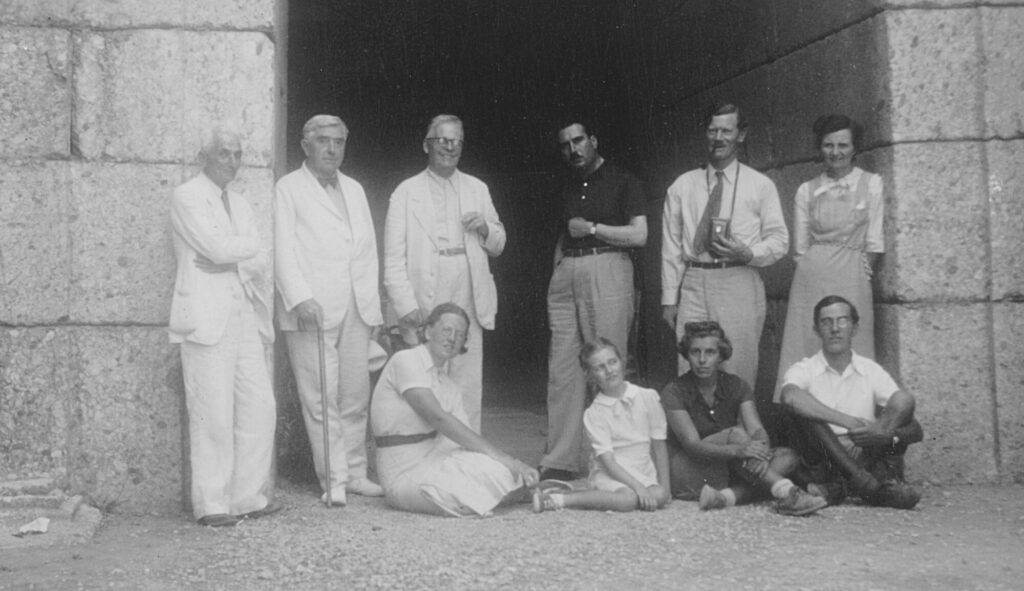

The 1939 dig was led by Prof. Alan Wace, from the University of Cambridge. He brought with him his wife, Helen, his daughter, Elizabeth Wace (later French), and his three postgraduate students: Helen Thomas (later Waterhouse), Frank Stubbings and Vronwy Fisher (later Hankey), as well as two interested undergraduates from the University of Oxford (Michael Fuller and Colin Kraay). Others present included Friedrich Wilhelm Goethert, a Roman art historian.

Image courtesy of the Mycenae Archive

Digging took place at several locations around the settlement. Much of the physical work was carried out by residents of the surrounding villages, many of whom had dug at other sites. The students’ main task was to supervise and record progress.

Nowadays this is quite straightforward. Everything is recorded, aided by unlimited photography, standardised recording forms and a detailed strategy set by the dig director. In 1939, however, each student had a notebook to jot down diary entries and sketch what they found. Photographs were rarely taken because cameras were much slower and more expensive to use. Museum storage space was scarce so objects deemed of low archaeological value, like unpainted pottery sherds, were routinely thrown away. Alan Wace delegated responsibility for the trench-side recording strategy to the students, so each of them had to exercise their own archaeological judgement a lot more than today, individually choosing what was important to record and keep.

Image: S. Aulsebrook, CC BY-SA 4.0 licence

Reconstructing Metal Recording Strategies

By comparing the students’ and dig director’s notebooks, Helen Wace’s diary, museum records and the published reports, each student’s metal recording strategy could be reconstructed. Details about day-to-day digging practices were provided by Elizabeth French who, despite only being eight-years-old at the time, retained a phenomenal memory of the dig.

The research revealed that each student had their own metal recording strategy, which was linked to their involvement in previous digs elsewhere, and did not share tips with each other. Vronwy Fisher had the most experience of uncovering prehistoric metals and had learned to keep all metal finds, even when poorly preserved. In contrast, Helen Thomas had previously excavated Iron Age graves, with well-preserved metal artefacts neatly presented in their original position. Tasked at Mycenae with supervising the digging around the Treasury of Atreus tomb, including the “Atreus Bothros”, she faced very different circumstances: many finds without clear association to buildings or graves and an unstratified rubbish tip filled with thousands of fragmented objects. She adopted a metal recording strategy of keeping all the gold, a well-preserved Iron Age pin and a couple of lead artefacts that interested her, but otherwise discarded more than 60 metal objects, almost all of which were bronze. The only record for posterity was a brief descriptive line in her notebook.

© S. Aulsebrook, CC BY-SA 4.0 licence

The Impact of World War Two

The German invasion of Poland came three days after the trenches were backfilled. The more valuable objects, like those of gold and ivory, were sent to the National Archaeological Museum at Athens and the local Archaeological Museum of Nauplion received the remainder. Postwar, the collections of both were left badly disordered. Helen Wace led the reorganisation efforts at Nauplion, taking the opportunity to remove objects of low archaeological value from the storerooms, especially those of iron and bronze, to make room for future finds.

Publication was also affected. Only Frank Stubbings contributed to the published dig reports and as Alan Wace passed away before his continuing excavation campaign at Mycenae ended, no full account of the 1939 season was ever produced. Publication of the “Atreus bothros” focused on its importance for dating the construction of the Treasury of Atreus tomb (ending a fierce debate with Sir Arthur Evans) and defining pottery assemblages for dating purposes.

© G. Todd, Public Domain

Lessons for Future Research

Many famous ancient sites, like Mycenae, were mainly excavated before more systematic digging and recording strategies were developed. This earlier evidence must be sensitively integrated into our modern interpretations, paying attention to what has survived and what may have been lost. Studying past digging and recording practices is therefore just as important as considering, for example, preservation conditions. This is especially important for metals because, although we think of them as strong and durable, various different factors (recycling, looting, corrosion, etc.) means that they are much less well-represented in the archaeological record than many people tend to presume. Investigating the Mycenae 1939 dig season has revealed how much variation there could be, even within a single team. Common assumptions by modern researchers, such as expecting different treatment of precious and base metals, have been shown to be incorrect; at Mycenae in 1939, only gold was treated specially, and finds of silver, the other ancient precious metal, were not all kept by the trench supervisors.

© S. Aulsebrook, CC BY-SA 4.0 licence

Unfortunately, in the case of the “Atreus Bothros”, a very particular set of circumstances effectively wrote its cache of metal artefacts out of the archaeological record. Although it is no longer possible to study the objects, returning to the original field notes has allowed the existence of this important group of metal artefacts to be rediscovered and integrated into our understanding of how metal was treated in the past. Currently, it is the only evidence we have at Mycenae for metal being deliberately thrown away as rubbish by Late Bronze Age people, rather than being accidentally lost or intentionally placed in graves or special deposits for storage and ritual reasons. Given that metals are recyclable, this profligacy could imply Mycenae had such secure and abundant access to bronze at this time that its wealthier households developed the habit of throwing away worn out bronze implements, rather than having them repaired.

References:

S. Aulsebrook, (2022). THE IMPACT OF ARCHAEOLOGICAL RECORDING ON THE STUDY OF METAL ARTEFACTS. MYCENAE 1939: A CASE STUDY. Annual of the British School at Athens, 117, 415-455. doi:10.1017/S0068245422000016

This article can be re-printed with photographs (except for those provided by the Mycenae Archive) free of charge provided that the source is published

The research presented here was funded by the National Science Centre of Poland (NCN) as part of the Sonata 14 programme, grant DEC-2018/31/D/HS3/02231, and hosted by the University of Warsaw. The complete publication is available to read for free here.

Author:

Stephanie Aulsebrook is an archaeologist working on metals from Late Bronze Age Greece at the University of Warsaw. Her main research interests are the social role of metals in the past and the reconstruction of “object biographies”, the stories of objects from their design and manufacture through to their use and eventual deposition in the archaeological record. She is a member of the Well Built Mycenae publication team.

Cover: Gold beads excavated from Mycenae, © M. Łapińska/P. Jurkowska, ed. Archeowiesci

Editing: J.M.C.