I opened the first box with fragments of pottery vessels. I took out, one by one, the artefacts kept in paper bags bearing still visible, but already faint labels written by professor Chmielewski nearly a quarter of a century earlier. I looked at the fragments and then had an idea!

Ciasna Cave – early fascination

Professor Chmielewski conducted excavations in Ciasna Cave in 1969-1970. It was a small cave, known only to local people, who filled it and blocked its entrances because foxes lived inside. One could look for a mention of this cave in scientific publications and find nothing. But it became the first step to my fascination with the Lusatian culture and pushed me towards the archaeology of Polish caves. I had mixed emotions in 2018 when I agreed to analyse some of the artefacts unearthed in Ciasna Cave. What can be interesting about badly damaged materials that are difficult to analyse and whose original archaeological context has not been preserved? You must remember that the upper layers of the sediment in caves are almost always badly mixed and, consequently, artefacts from the Bronze Age, Early Iron Age, modern period, and even the Palaeolithic might be found directly next to each other. I was so wrong…

© Archive of the Faculty of Archaeology UW, CC BY-NC-SA 4.0 licence

Archaeological „puzzles”

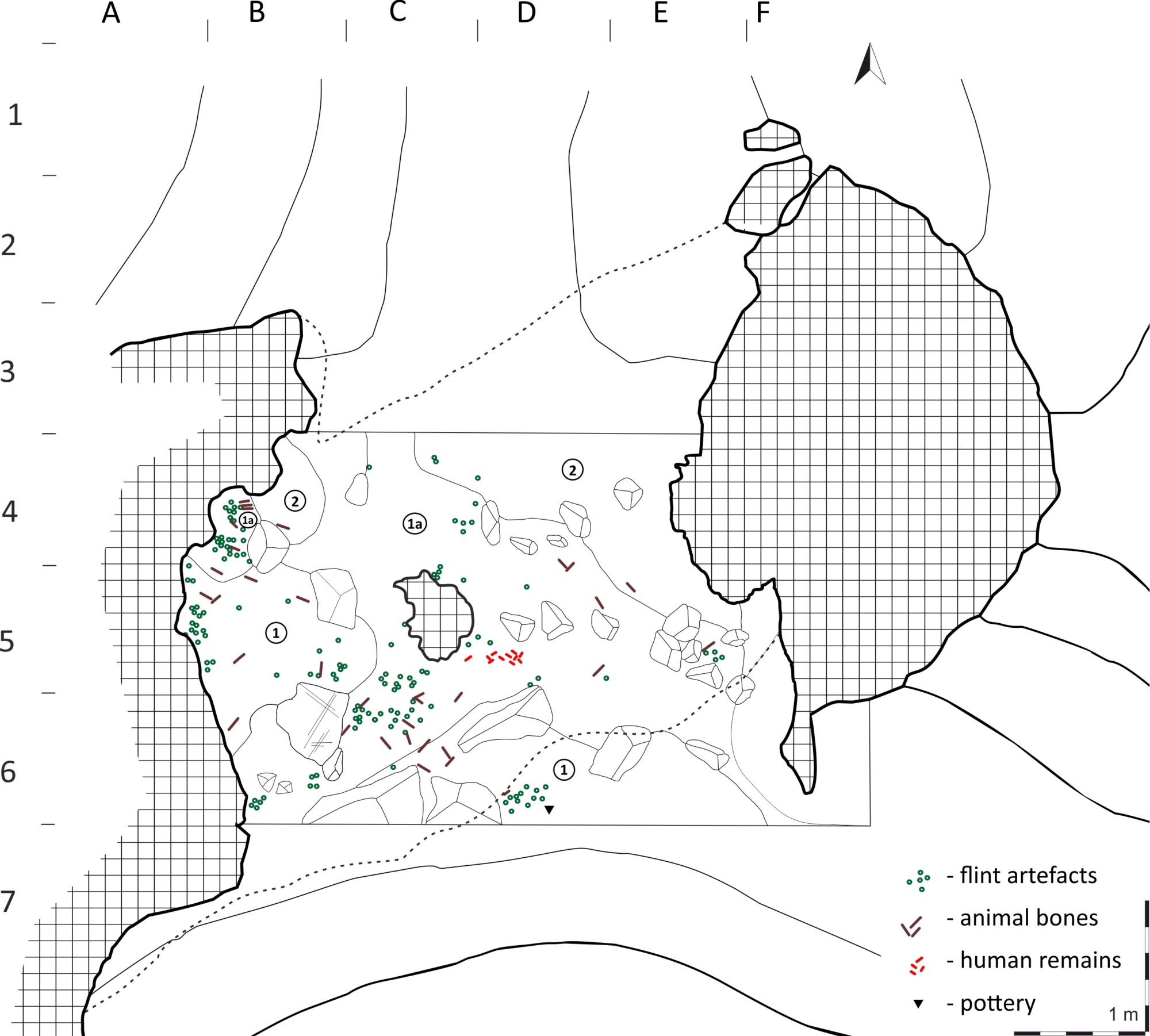

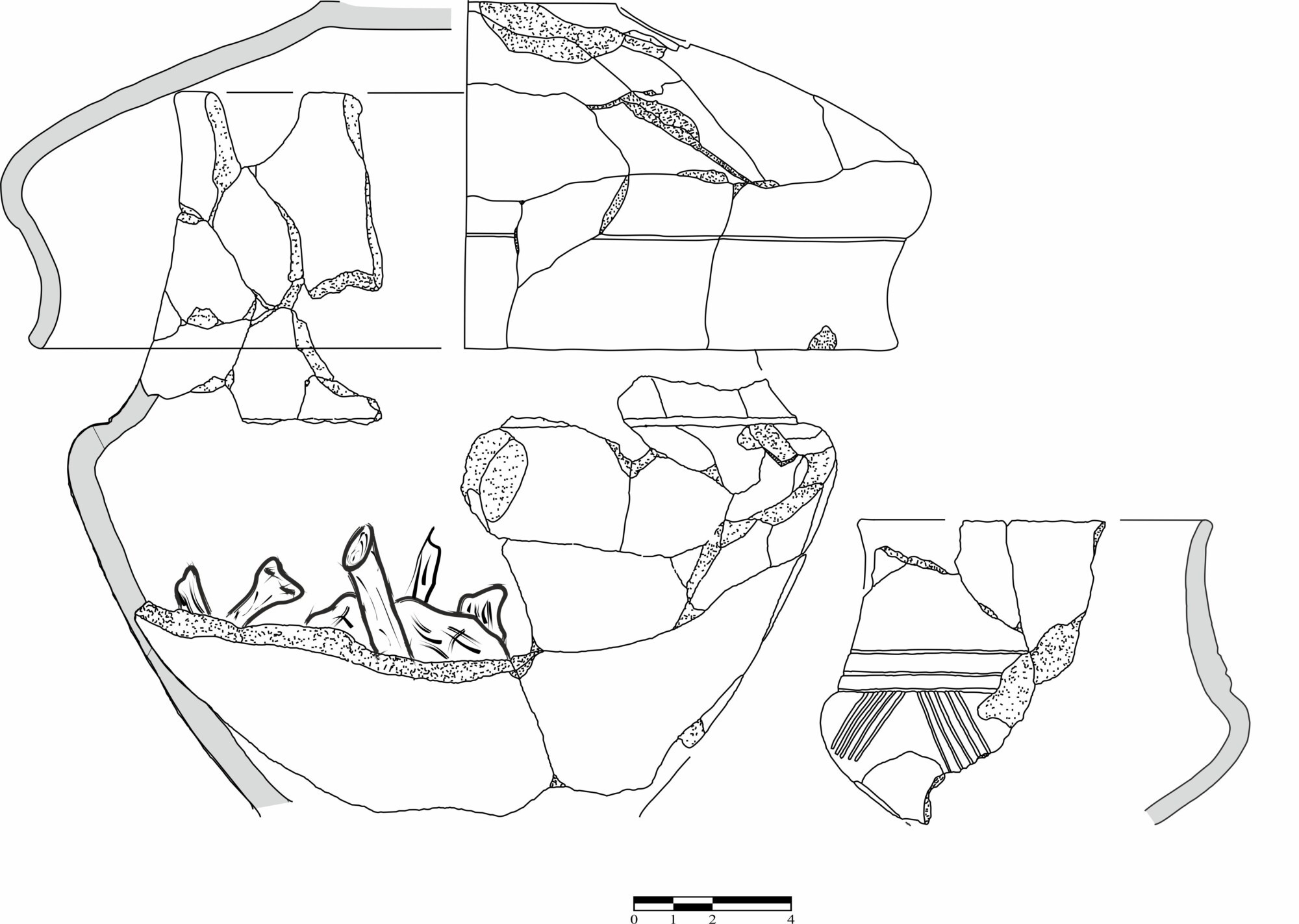

I began my work from matching the pottery fragments and their graphical reconstruction on the basis of the material found by professor Chmielewski. It was like doing puzzle – a thousand elements to match, but in this case half of them were missing. However, my hard work returned good results. It turned out that there were three vessels that the people of the Lusatian culture deposited in the cave in the Late Bronze Age or Early Iron Age: a bowl, a vase and a small vase-like vessel. I wondered how to interpret such a group of artefacts. All the vessels were made in the same manner: they were reduction-fired (oxygen did not reach the vessels during the firing process, which resulted in their characteristic dark grey colour) and their surfaces were finished in the same way. In other words, it seemed like one and the same person made them 2700 years ago, and, on top of that, with exceptional accuracy. Interestingly, despite a high degree of fragmentation, considerable portions of the vessels could be reconstructed, both by matching pottery pieces and by drawing. For instance, 75-80% of the bowl has been preserved. This is not typical – the state of preservation of most vessels from caves precludes a proper analysis. We usually find small and isolated fragments with no distinctive features, which makes it difficult to identify them and associate with a particular archaeological culture.

© M. Dąbski, CC BY-NC-SA 4.0 licence

I follow the archaeological clues…

The next step was to analyse the documentation. I looked through the drawings showing the distribution of the pottery fragments at various depths and concluded that the vessels were deposited together in one spot. This is also indicated by their state of preservation, sufficient for a relatively precise reconstruction. Well… I still did not understand why should anyone walk in the forest and carry them to bury in a narrow tunnel, in which he would not be able to stand up easily. And then I realized the significance!

Photo: M. Bogacki, drawing: G. Czajka, CC BY-NC-SA 4.0 licence

Playing the archaeological bingo

I have a pottery assemblage characteristic of cremation burials! The vase would function as the urn to accommodate the ashes of the deceased, the bowl would cover it on top, while the vase-like vessel would be an addition – a grave good. Perhaps it contained food which should symbolically facilitate the journey of the individual in the afterlife.

© G. Czajka, CC BY-NC-SA 4.0 licence

More indirect evidence

Fine, so we have the grave, but where are the bones? If they were in the urn, the professor would definitely have collected them and written about them in his diary. So I consult the diary and, indeed, the professor mentions that he found four fragments of a skull, “perhaps human skull”, in the trench. Unfortunately, these small bone fragments were lost and it is now impossible to analyse them.

© M. Dąbski, CC BY-NC-SA 4.0 licence

How can we prove that there was a burial in Ciasna Cave if we have no bones?

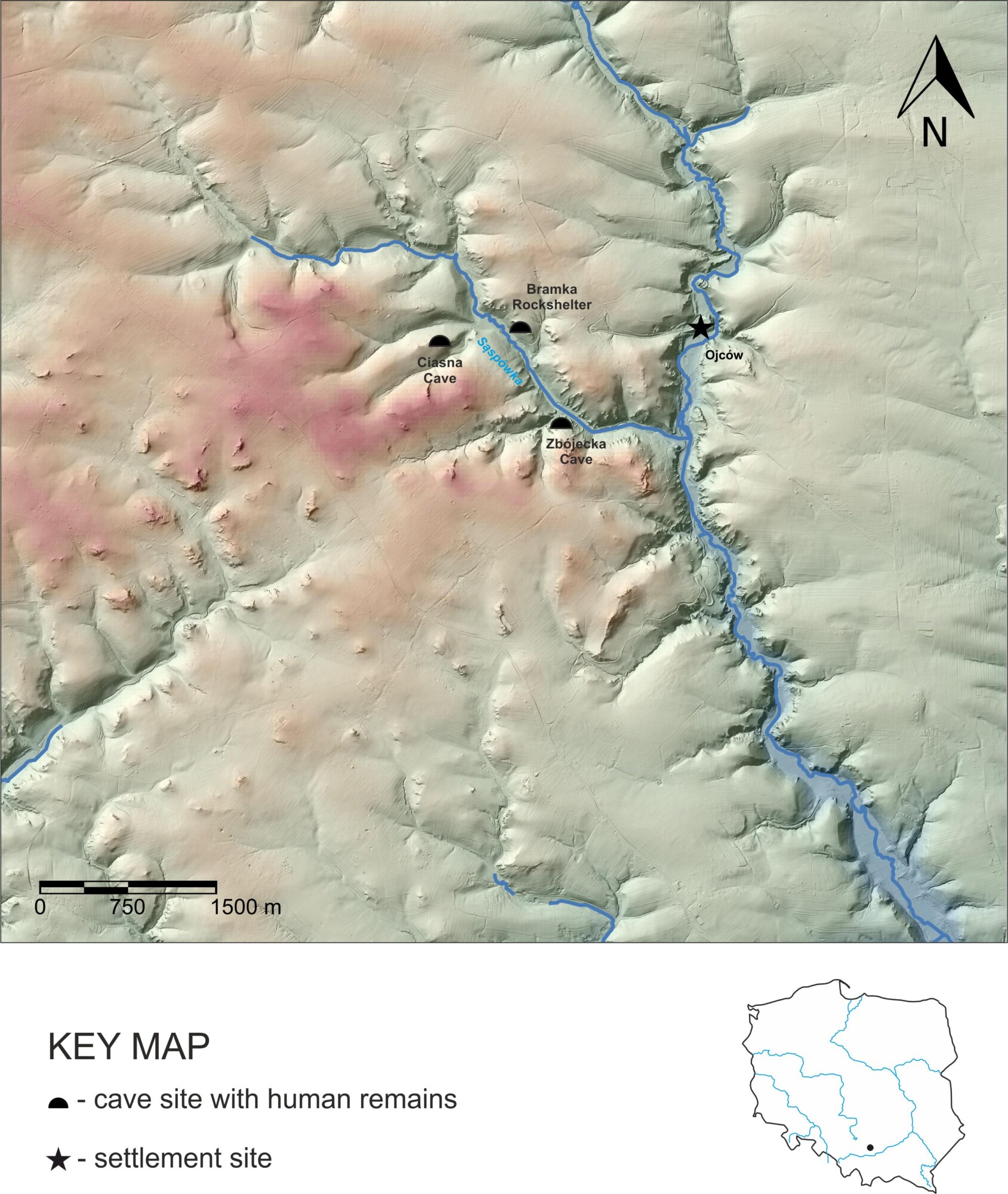

It’s a hard nut to crack (I thought). After all, it is impossible to find any mention of cave burials from that period in the Polish territory in the scientific literature. Luckily, at the same time Dr. Małgorzata Kot and Dr. Elżbieta Jaskulska analysed human bones and artefacts from a site located nearby – Bramka Rockshelter. Radiocarbon dating results left no room for doubts – Lusatian culture burial was found also there. It was different, however, since it had no grave goods and differed from the classical cremation burial used at that time.

© M. Dąbski, CC BY-NC-SA 4.0 licence

That cannot be an accident

Within the same valley, we have two examples of Lusatian culture burials deposited in caves. We did not have to wait long for another discovery of this kind: two calcanei in the collection of the University of Wrocław, unearthed in Zbójecka Cave by Ferdinand von Roemer in the 19th century, were initially incorrectly identified as animal bones, but their recent analysis showed they were human remains. Radiocarbon dating established their chronology at the same time as those from Bramka Rockshelter. In this case, it is also a skeletal burial, rather atypical in this period.

Perhaps it was just a symbol?

There is another explanation for the riddle of the missing bones from Ciasna Cave. Let’s see… They might have never been there. You will probably think: “How come? A grave without the remains of the deceased?” Well, yes. One of the traditions known not only from prehistory, but also from modern times is a symbolic burial. It is possible that the set of funerary vessels deposited in Ciasna Cave did not contain burned remains of the deceased or that the amount was very small – just a handful of bones. Even if the skull fragments mentioned by professor Chmielewski really belonged to a human, we cannot be sure that we could associate them with the Lusatian culture. Relics of another badly damaged vessel, an amphora with beautifully ornamented, horizontally pierced handles, which could be associated with the Złota culture or Corded Ware culture, were found at the site. They were related Neolithic cultural entities, whose traditions included deposition of amphorae and other objects in graves of their dead. Nevertheless, the Late Bronze Age or Early Iron Age deposition of Lusatian culture vessels, perfectly corresponding with those usually found in burial assemblages, cannot be accidental and indicates that it was not a Neolithic burial.

© G. Czajka, CC BY-NC-SA 4.0 licence

How can we explain this?

In a close proximity of the three caves, in the area of the Ojców Castle, there was a Lusatian culture settlement in the past. Perhaps the human remains unearthed in the caves belonged to the members of this community. No cemetery which could be connected with this community has ever been found in the vicinity. This might mean that the local people adapted to the particular terrain which made it impossible to establish a big cemetery in this area. Consequently, they used caves and rockshelters, which probably fascinated them with their inherent mysterious character, for funerary purposes. They might have interpreted the dark opening leading down as the transit to the afterlife.

© M. Dąbski, CC BY-NC-SA 4.0 licence

Afterword

A few years later, I still find pleasure in thinking of the analyses of the artefacts from Ciasna Cave. Was that the end of our work on Lusatian culture artefacts? Of course not! The three modest vessels unearthed in Ciasna Cave turned out to be just the first step to the adventure, that is, discovering the customs and traditions of the people who lived in the Cracow-Częstochowa Upland in the Bronze Age and Early Iron Age. I am quite sure that my heartbeat will speed up more than once during analysis of the materials from other caves, and our knowledge of the past will become greater with new discoveries.

This article can be re-printed with photographs free of charge provided that the source is cited

Author:

Grzegorz Czajka, MA – archeologist of the Bronze Age and Early Iron Age. His research interests include pottery industry and the phenomenon of cave exploitation in the territory of modern Poland by prehistoric societies. Apart from his work, he is fascinated by numismatics, especially Polish coinage from the rule of the Vasa dynasty. He is currently working on his doctoral dissertation and studying at the Doctoral School of Humanities of the University of Warsaw.

This text was funded by the project entitled “From caves to public: A series of popular science articles published on the archeowieści.pl blog, showing a multidisciplinary approach in archaeology, based on the results of our researches in the Ojców Jura” from Inicjatywa Doskonałości – Uczelnia Badawcza programme. Research on the caves of the Sąspowska Valley was funded by the National Science Centre, project: SONATA BIS 2016/22/E/HS3/00486.

References:

Chmielewski W. (ed.) (1988) Jaskinie Doliny Sąspowskiej. Tło przyrodnicze osadnictwa pradziejowego. Warszawa, Prace Instytutu Archeologii UW.

Czajka G. (2019) Źródła archeologiczne z holoceńskich nawarstwień sedymentu Jaskini Ciasnej z badań w latach 1969-70 i 2018. (BA dissertation).

Project website: https://www.dolinasaspowska.uw.edu.pl