Llamas (Lama glama) and alpacas (Vicugna pacos) are the only large, domesticated, and endemic mammals in the Peruvian Andes. They had immense significance for all pre-Columbian Andean cultures by providing essential resources such as meat, wool for textile production, bones for tool and ornament manufacturing, and dung used as fuel and fertilizer. Llamas and alpacas held an important place in pre-Columbian iconography. Their images were depicted on pottery, textiles, and on rocks in the form of petroglyphs and carvings. More robust llamas also served as pack animals and traversed the Andes in trade caravans.

Unfortunately for zooarchaeologists (scientists studying the relationships between humans and animals in the past), all South American camelid species are genetically related, which complicates their species identification if based solely on animal bones recovered during archaeological fieldwork. For this reason, in Andean zooarchaeology, they are conventionally referred to as “camelids.”

© W. Tomczyk, under licence CC BY-NC-SA 4.0

The historical and current distribution of camelids

The contemporary distribution of camelids in Peru is limited to high-altitude grasslands in the southern ranges of the Andes. Until recently, it was believed that these territorial limitations were a continuation of pre-Columbian breeding practices. Consequently, if archaeologists found camelid bones on the Pacific coast, they assumed that such bones arrived there in the form of imported, processed products rather than as live animals. However, in the last two decades, intensified isotopic analyses of camelid bones from multiple sites in various regions of Peru — including those studied by Polish scientists from the University of Warsaw at Castillo de Huarmey — have shown that camelids were locally raised in all ecological zones of the western slopes of the Andes. Still, reconstructing the history of camelid husbandry on the eastern neotropical slopes covered by the Amazon jungle is more problematic. Are the results from archaeological studies in fact confirming the presence of camelids in the jungle? Did llamas traverse the Andes not only along but also across them?

Public domain

Most archaeological research on the eastern Andean slopes focuses on the extreme edges of contemporary Peru: the borderlands of the modern departments of Cajamarca and Amazonas on the border with Ecuador, and at the far south, in the Cuzco region. In both areas, archaeological research is mainly conducted in the vegetation zone called either montaña or selva alta, which is covered by subtropical forests at 300–3300 meters above sea level (m.a.s.l.) In northern Peru, the breeding of camelids has already been confirmed for the Formative Period (around 900–200 BCE) by isotopic studies at the Pacopampa site, located at an altitude of 2500 m.a.s.l.. At Huayurco, an archaeological site located only at 450 m.a.s.l. a similarly dated offering of a young camelid was found beneath the floor of a building. Camelid breeding must have been advanced during the Late Transitional Period (around 1100–1476 CE) and the Late Horizon (1476–1532 CE), as studies at Kuelap, a fortress of the Chachapoya culture, revealed that camelid bones constituted the majority of analyzed animal remains. Another piece of evidence came from the selva alta of the Amazonas department, where scientists located a series of rock paintings depicting camelids enclosed in circles interpreted as corrals, or walking one behind the other — just like they do in a caravan.

The Metropolitan Museum of Art collection

Public domain

In the south, in the Cuzco region, poorly preserved camelid bones were found at Espíritu Pampa, an enclave associated with the Wari culture of the Middle Horizon (around 600–1100 CE), located about 1400 m.a.s.l. At the Qochapata site, located in the Amaybamba River valley at ca. 2250 m.a.s.l. , scientists located fragments of a road wide enough for a caravan to pass and many stone enclosures for camelids. It was dated to the Late Horizon, but it is possible that such an Inca road was modeled after earlier Wari-period infrastructure.

Verdict: Llamas as occasional visitors to the eastern slopes of the Andes

In sum, previous research shows that camelids (probably larger, more resilient llamas) frequented the high, transitional parts of the Amazon jungle. They were used as pack animals, facilitating trans-Andean transport of Amazonian luxury goods such as coca leaves or parrot feathers. Trade contacts likely existed from the Formative Period, intensified in the Middle Horizon, and survived until the recent past. An example confirming the existence of such an enduring tradition is the story of archaeologist Charles M. Hastings, who encountered a loaded llama caravan during fieldwork in the subtropical valley of the Urubamba River in 1980.

Public Domain

Additionally, large quantities of animal bones found at sites such as Pacopampa or Kuélap suggest that small-scale camelid herds were raised for local use. Unfortunately, the current state of knowledge does not allow us to demonstrate how common camelid occurrence was in the lowest eastern Andean climatic zone called selva baja. Camelid breeding attempts could have failed due to the unfavorable climate. The same Amazonian humidity, which potentially hampered camelid herding, could have also accelerated the decomposition of their remains. However, mammal bones are well preserved in the tropical forests of Mesoamerica. It is thus possible that the lack of evidence for the presence of camelids in the Andean jungles results from excavation strategies and a preference for conducting work at mountain sites. A change in tactics and the emergence of more intensive work in humid areas could answer the titular question soon.

This article can be reprinted free of charge, with photos, and with the source indicated

About the author:

Weronika Tomczyk – an anthropological archaeologist specializing in zooarchaeology, isotopic studies, and pre-Columbian archaeology. She recently received her Ph.D. at the Department of Anthropology, Stanford University (USA). Her dissertation focused on the animals influencing the expansion of the Wari empire in present-day northern Peru.

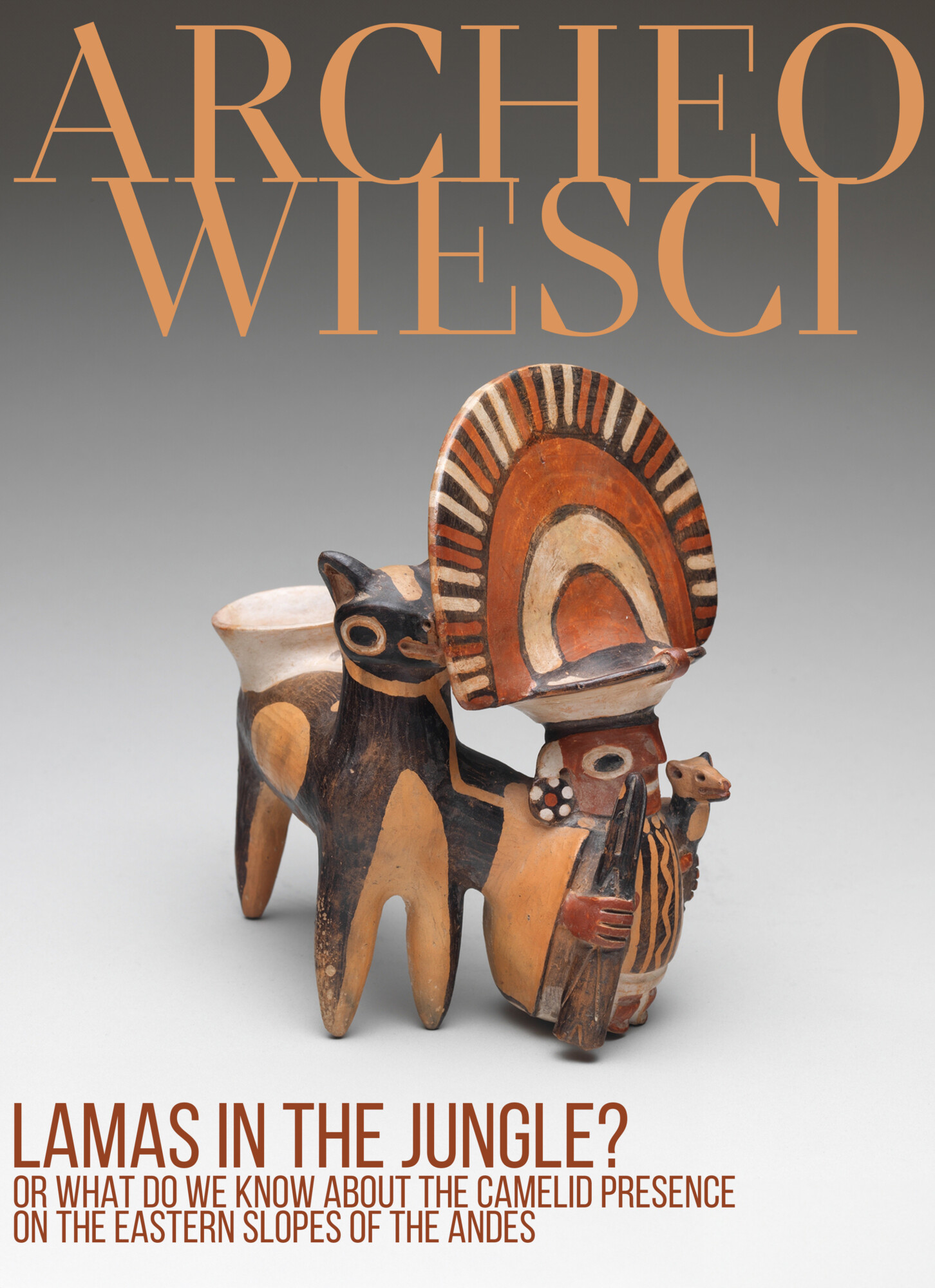

Cover: Recuay culture ceramic vessel depicting a man with a camelid

The Metropolitan Museum of Art collection, Public domain, ed. K.K.