Ptolemaic Pathyris is known for its rich collection of papyri and ostraca, which survive in excellent condition, buried in the ruins of the city. Thousands of texts, describing the everyday life of the ancient Egyptians and belonging to the archives of the local temple and notary’s office, but above all to the archives of the ordinary families living in the town, were discovered here in the late 19th and throughout the 20th centuries. A businesswoman, an inheritance dispute, or an unexplained murder — this is only the beginning of the story.

Although the archaeology of Ancient Egypt is dominated by studies of tombs, temples, and the realm of the elite, The Ptolemaic Pathyris Project wants to change this by showing how much we can learn about ordinary people and their everyday lives.

© D.F. Wieczorek, published under CC BY-ND 4.0

Time Capsule

Pathyris is the Greek name for the ancient Egyptian town of Per-Hathor (literally “House of Hathor”), located about 30 km southwest of Luxor, and situated on top and over the slopes of the East Mountain of Gebelein (“two mountains” in Arabic), in the Gebelein micro-region (Egypt). What makes this town unique is its strategic role as a stronghold controlling the navigation on the Nile in this area. Due to its significance, the locality has been inhabited since prehistory, and received a new impulse for development after 186 B.C., when the Great Revolt in Upper Egypt was suppressed. A Ptolemaic military camp was established there between 165 and 161 B.C., where local and foreign people could serve as soldiers serving for pay (in contrast to kleruchoi, obligated to provide military service in return for plots of land). Pathyris was the capital of its nome (administrative unit) from the 2nd century B.C. to 88 B.C. After another revolt, during the reign of Ptolemy X Alexander, Pathyris disappeared from the written records. What happened? Letters from Platon, a military commander, have been preserved, praising the loyalty of the inhabitants of Pathyris and promising the arrival of military aid. The town was most likely then captured and destroyed by the rebels and its inhabitants had to flee quickly, leaving their family documents behind. These archives can be compared to time capsules documenting the lives of families and individual people, through private letters, wills, real estate leases, sale agreements, and tax receipts.

Ptolemaic Pathyris Project: Digital and Archival Archaeology

Our project envisions interdisciplinary research on the urban layout and residential architecture of the town of Pathyris, based on a wide range of sources: archival (unpublished results of previous excavations), papyrological (about 1,300 documents), and geospatial (preserved remains of the town on the hillside) data.

© W. Ejsmond, published under CC BY-ND 4.0

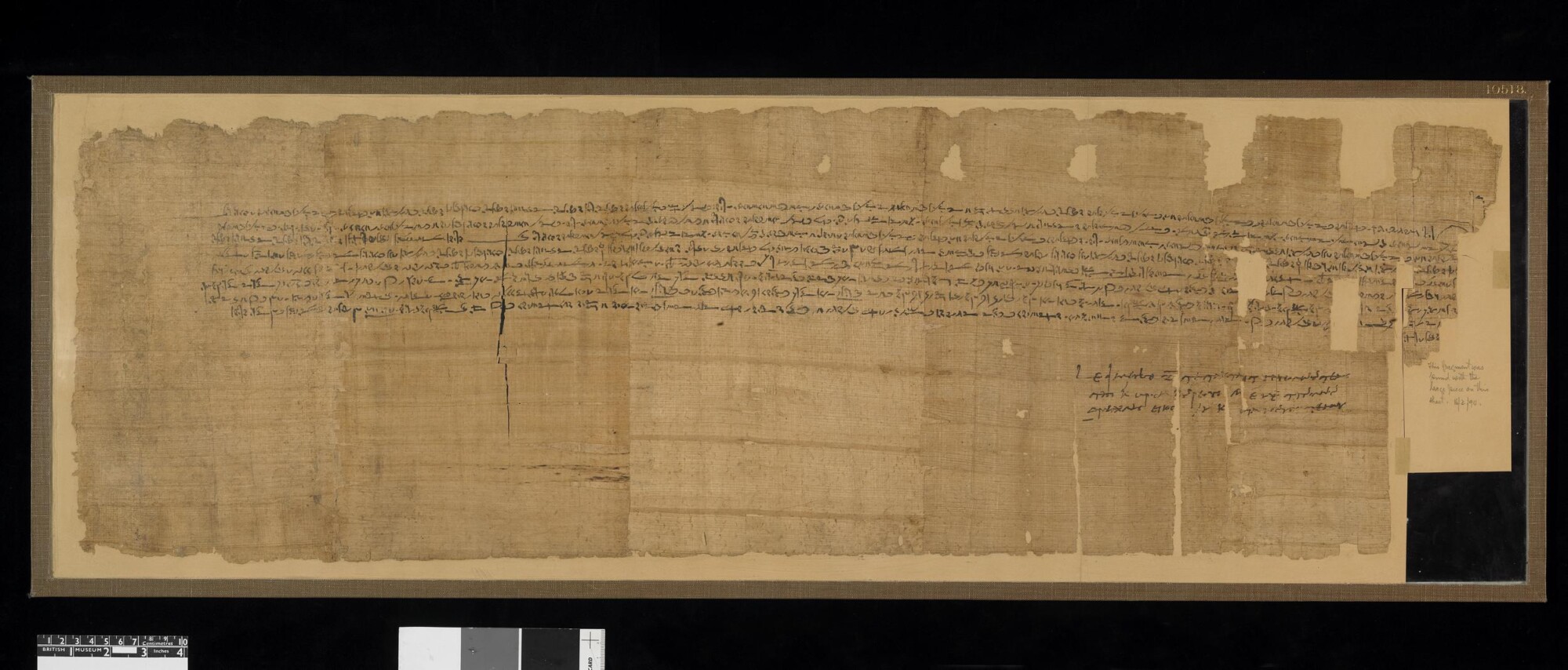

What makes the town unique is the large number of Greek and Demotic (the ancient Egyptian script in use between the 7th c. B.C. and 5th c. A.D.) papyri, ostraca, and wooden tablets found in archives maintained by the town authorities, temples, and individual families. These documents show how the authorities attempted to Hellenize the town several times, eventually giving birth to a bilingual community with coexisting Greek and Egyptian practices, institutions, and languages. Thus, the project’s sources offer a unique glimpse into various socio-economical facets of the Ptolemaic society.

© The Trustees of the British Museum, published under CC BY-NC-SA 4.0

Despite its significant presence in the written records, which cannot be overlooked by any scholar dealing with the Ptolemaic period in Egypt, Pathyris has remained largely unexplored by archaeologists. Moreover, due to the expansion of modern housing in the nearby vicinity of the archaeological site, many traces of this ancient town have been irretrievably lost by now. Therefore, there is a risk of its complete disappearance, not only from the face of the earth, but also from the scholarly debate.

© W. Ejsmond, published under CC BY-ND 4.0

How, then, can we recreate its appearance? What sources do we have at our disposal? The latter are many and varied. First, the archival sources, namely the unpublished Notebook with Sketches as well as photographs from Italian excavations conducted by Ernesto Schiaparelli, at the beginning of the 20th century. The Notebook combines drawings and descriptions of excavated architectural structures with detailed measurements of the preserved walls — the plans include information about the dimensions of individual rooms, as well as wall thicknesses, placement of stairs, ovens, etc. This information, coupled with photographs showing houses in the town, sometimes preserved up to 2–3 meters above the ground, will allow us to understand the original town plan and individual buildings.

Archivio Museo Egizio C00696, published under CC0 1.0

Abundant, and often precise, information about the topography of the town and features of residential architecture can also be found in the papyri and ostraca discovered there. Documents such as contracts of sale or agreements on the division or leasing of property (houses and vacant plots) included several standardized elements: enumerations of typical building elements (e.g. courtyard, vaulted room) as well as of neighbors on all four sides. Analyzed jointly with the archaeological remains, these documents will allow for the reconstruction of the layout of larger parts of the town and, by identifying the characteristic elements of houses mentioned in the papyri (such as vaulted structures, dovecotes, light wells, etc.), put them in proper archaeological context. The analysis of papyri documentation will also allow for reconstructing the arrangement of town districts and the street grid within the town, as well as the approximation of the locations of public structures, such as temples and fortifications.

Finally, the reconstructed town plan will be embedded in the field thanks to georeferencing. In conjunction with the Digital Elevation Model (raster representation of the relief of the terrain), a hypothetical 3D visualization of Pathyris will be compiled, shedding light on how its architecture was adjusted to the natural topography of the East Gebelein Mountain. All the above analyses will add to our understanding of urbanization in the Ptolemaic period, by revealing whether the process of Hellenization was also reflected in the residential architecture and urban landscape of Pathyris, and how it compared to other Ptolemaic towns.

Archivio Museo Egizio C00741, published under CC0 1.0

A Businesswoman, an Inheritance Dispute, and an Unsolved Murder

Our research will provide a rare glimpse into the life of a provincial administrative center from the end of the Pharaonic epoch. We will try to understand the relations between its ancient Egyptian and Greek inhabitants and explore their lifeways by 3D-modeling the town itself. Thanks to the model, we will be able to journey through the town in the footsteps of a renowned businesswoman, Apollonia, called Senmonthis in Egyptian, and her husband Dryton, a Greek cavalry officer. We will not only try to determine exactly where they lived, but also where their other properties were located, including a vineyard, a vacant plot, and dovecotes. We will also discover the whereabouts of the property of Lady Tamenos, the subject of a long-standing inheritance dispute. Maybe we will also find the house of Kaies, whose body was found floating in a canal near the town. Pathyris was definitely not a sleepy provincial town where nothing ever happened!

Our project is a two-year research endeavor financed by the National Science Centre (Polonez Bis 2 program, grant no. 2022/45/P/HS3/01807), directed by Doctor Aneta Skalec of the Institute of the Mediterranean and Oriental Cultures of the Polish Academy of Sciences in Warsaw. It aims to reconstruct the urban layout and study the residential architecture of Pathiris, a flourishing multicultural Ptolemaic-period (322–30 B.C.) administrative center where Egyptians and Greeks lived side-by-side. This will help in understanding the mutual relations of both ethnic groups and everyday life in the provinces during the twilight of the Egyptian civilization.

© W. Ejsmond, published under CC BY-ND 4.0

This article can be reprinted free of charge, with photos, and with the source indicated

© J. Stępnik, published under CC BY-ND 4.0

Aneta Skalec – A papyrologist, archaeologist, and Roman lawyer. She graduated from the University of Warsaw (in Archaeology and Law) and is an Assistant Professor at the Institute of the Mediterranean and Oriental Cultures of the Polish Academy of Sciences in Warsaw. She has authored a monograph and several papers on papyrology and Egyptology, focusing on papyrological and archaeological sources, as well as on the diplomatics and use of graphic symbols on Late Antique papyri.

https://pan-pl.academia.edu/AnetaSkalec

https://orcid.org/0000-0001-9572-9029

Proofreading: S.A.

Editing: A.B./J.C.

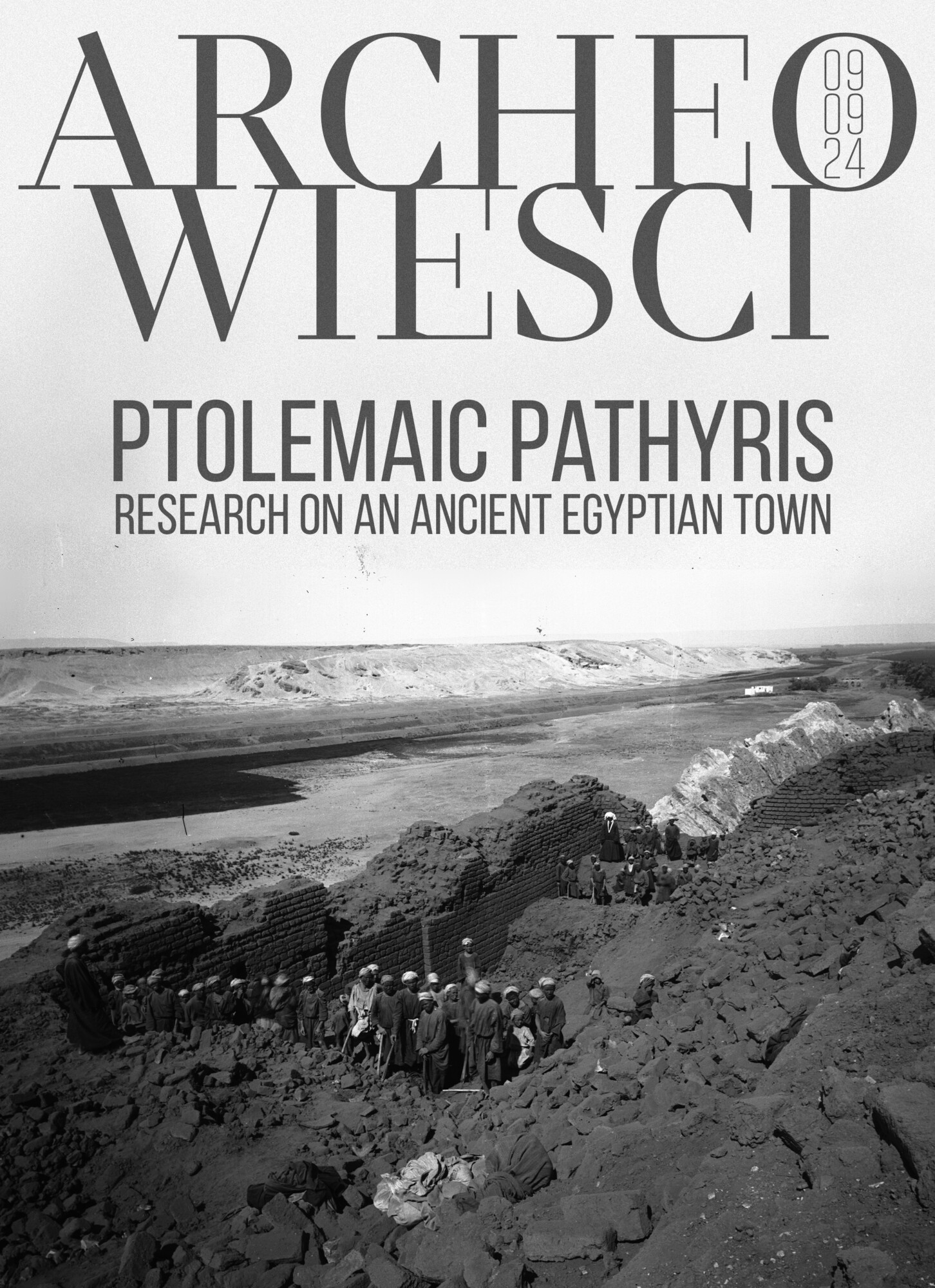

Cover: The summit of the East Gebelein Mountain with the remains of the city of Pathyris. Archival photograph from the Italian excavations at Pathyris in 1910, showing the ruins of the fortress, located on top of the East Gebelein Hill

Archivio Museo Egizio C00696, published under CC0 1.0, ed. K.K.