The summer of 9,750 BC (or 11,700 years before present) was warmer and rainier than usual in the area of the Kraków-Częstochowa Upland. At sunset, a solitary narrow-headed vole was walking across the hills, down to the Sąspow River and up to the highlands, in search of its favourite food to store for the winter, mainly shoots of grasses and sedges, every year more and more scarce and harder to find due to the advance of the forest. These were times of changes: only a few decades before, his great-grandparents were living in a suitable tundra environment with all the necessities: enough food in the summer, enough snow and ice in the winter to store their favourite grass seeds; in all the valleys were plenty of voles of his kind. Now all had changed. The solitary rodent was starving; he was the last of his kind in southern Poland. All his “family” moved northwards a long time ago because of global warming and the advance of the great forest.

Up in the sky, a silent owl was patrolling his territory as usual, in search of some succulent prey. Suddenly, in the dim light of the sunset, something moved along the boundary clearing of the forest; it was clearly an arvicolid, one of his favourite meals.

A silent flash of wings, a rapid rustle and, in a moment, the last Lasiopodomys anglicus in southern Poland became prey.

The nocturnal bird leapt into the sky, made some small turns to check if there was something else to eat but no, for that night it was enough, it was time to return to his nest with his prey firmly gripped in its claws. Taking just a moment to rest on a birch and eat, literally whole, his dinner, in a few minutes the owl was back in his home, a small cave which several millennia later humans would call “Ciasna”.

Is this little story real? What happened next? Who replaced the narrow-headed voles in the Kraków-Częstochowa Upland? Why were there so many changes around 9,750 BC?

These are some of the questions that we wanted to answer during our research on the ecological, environmental and climatic reconstructions of this area between the end of the Late Pleistocene and the beginning of the Holocene, a crucial moment also in the history of humankind.

© C. Berto, na licencji CC BY-NC-SA 4.0

A rodent, a bird of prey and a suitable cave. That is what we need to have the perfect “crime scene” for studying the climate of the past. Well, actually we need thousands of rodents (or better still, also insectivores and bats) and sometimes even more than just one cave in order to reconstruct the whole picture. And in this case, we also studied other small vertebrates and molluscs. But I don’t want to overcomplicate it; let’s stick to our plot.

Our “owl” is a Strigiform, a nocturnal bird of prey which usually loves arvicolids, but can also eat other rodents, insectivores, bats, amphibians, reptiles, fish, etc. They usually hunt during the night and, since they have no teeth, they need to swallow their prey whole. They can digest only the flesh and other soft parts, but the bones and fur are too heavy for their stomachs, so those are ejected in the form of “pellets”. These pellets fall onto the ground and, with time, the fur decomposes and only the bones and teeth remain. Inside a cave, these are usually buried by sediments over time and, if we are lucky enough, they come to us well preserved.

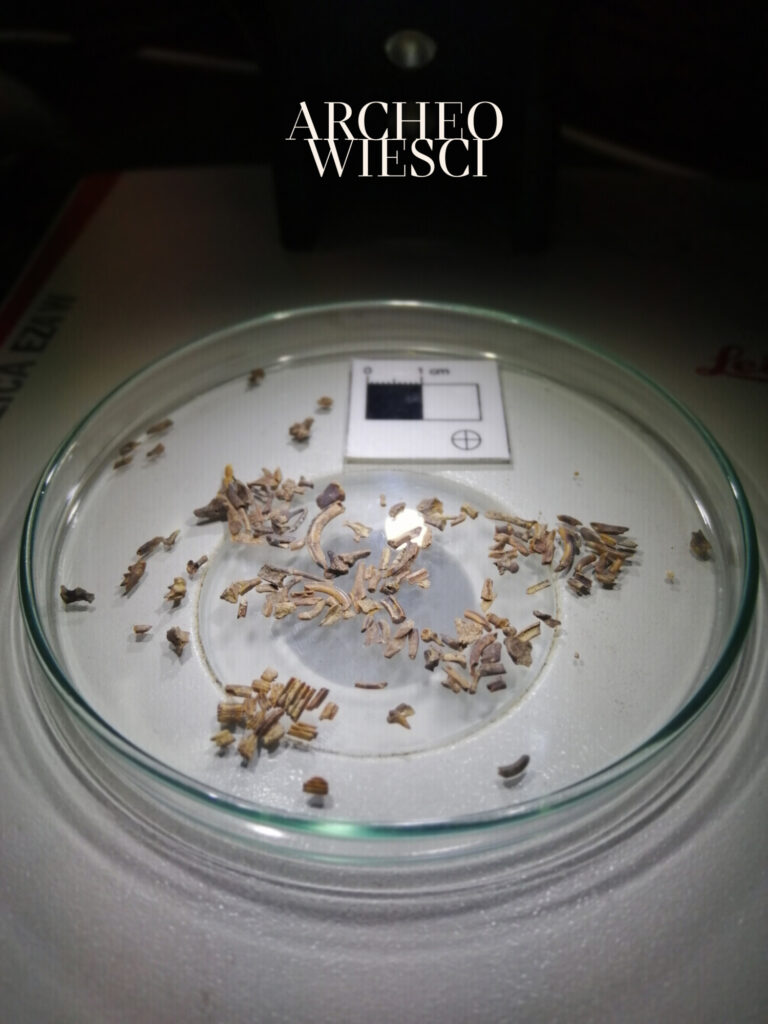

A few millennia later, in 2017, a team of University of Warsaw archaeologists came to dig in Ciasna Cave. They were searching for artefacts but also for other remains, so they brought with them sieves and water pipes, and they washed all the sediment which they excavated. Once dried, the sediment contained plenty of little bones which they collected (calling them “dziurawki” and joking about this lilliputian population who inhabited the cave). The bones arrived in plastic bags at the Faculty of Archaeology and the team gave them to me during my first days in Poland, in 2019.

© C. Berto, CC BY-NC-SA 4.0 licence

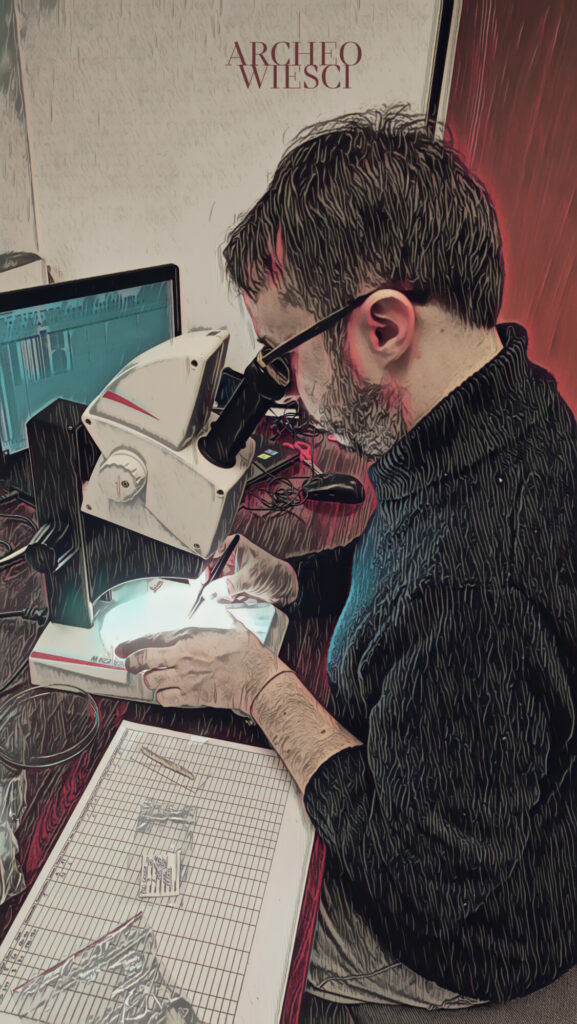

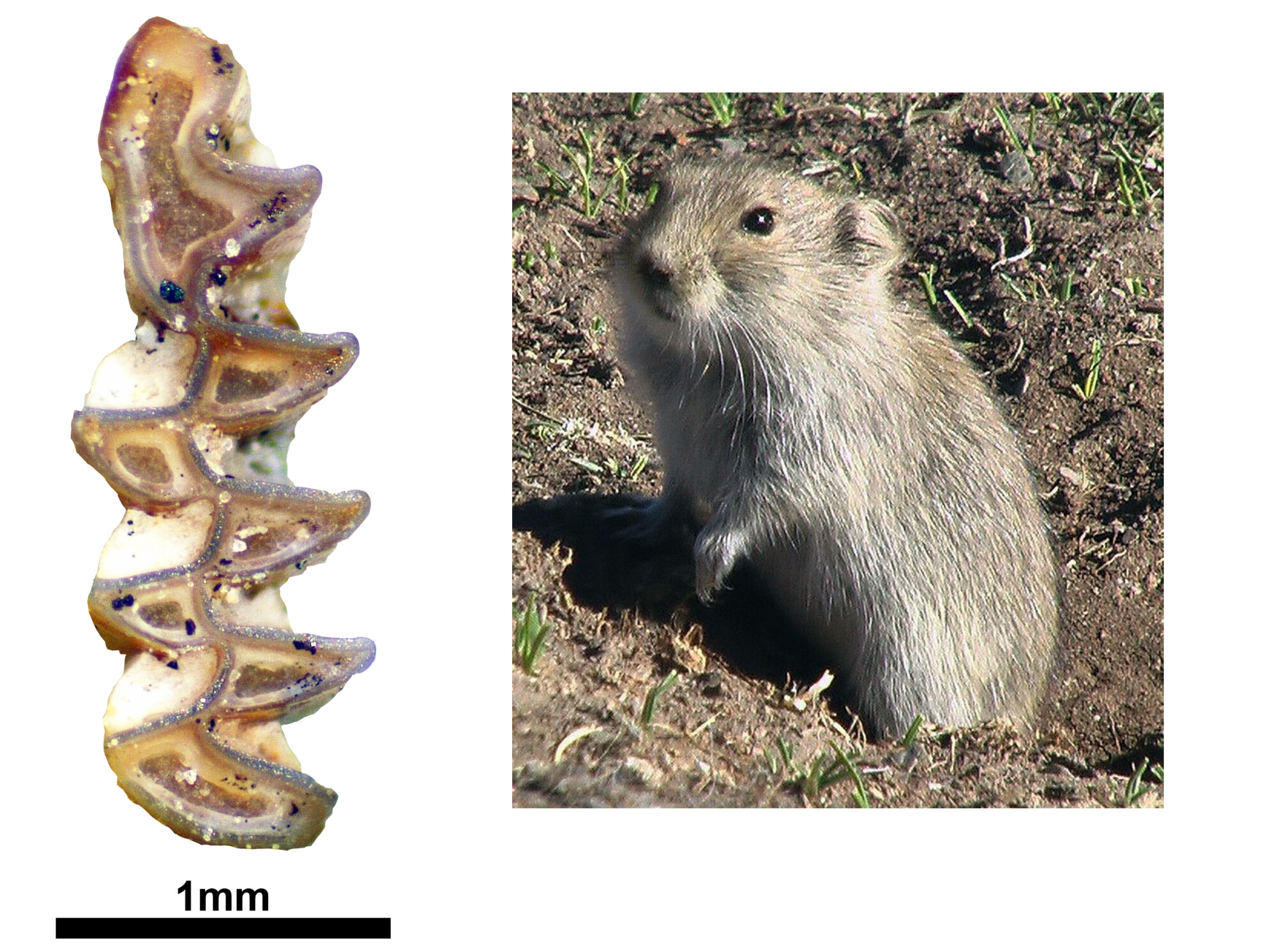

To identify the small mammal remains I used a stereomicroscope: every useful tooth and bone is carefully screened and, based on its morphology, it is possible to recognise the species. At that time I already knew that the four layers of Ciasna Cave were probably dated to the Early Holocene, and I expected species which love to live in broadleaf forests, forest edges or little clearings, usually bank voles and European pine voles. Layer after layer, I was writing in my database their Latin names: “Layer 1: Clethionomys glareolus, Microtus (Terricola) subterraneus, Clethrioniomys…, Layer 2: Clethionomys glareolus, Microtus (Terricola) subterraneus, Clethrioniomys…”, but once I started to study Layer 4 something changed. The bones belonged mostly to tundra voles (Alexandromys oeconomus), which, despite its common name, is a species more adapted to boreal or birch forests; some solitary teeth of narrow-headed voles (Lasiopodomys anglicus) appeared too, while bank voles and pine voles were almost absent! Excited, I screamed to my colleagues that we were on the brink of discovering evidence for a climate change in the past.

Why did I do that? Because small mammals, together with other small vertebrates and molluscs, are usually dependent on the landscape and almost every species is related to a specific habitat and climatic conditions. Thus, we can estimate with some precision the environment and climate of the past by studying the fossil communities and their changes through time.

These climatic and environmental reconstructions are very useful for the archaeologists who want to better understand how humans in the past adapted to climate changes.

© G. Czajka, na licencji CC BY-NC-SA 4.0

After completing the Ciasna Cave small mammal dataset, together with other researchers who study molluscs and other small vertebrates, we were curious to investigate if such a “climate change” on the edge of the Holocene (our current geological epoch) was visible in other places around Poland, and if it affected different animal communities. Thus, we “dug” into the previous published works to collect much more data and, after a few months of research and discussions, we added our little contribution to the understanding of past climate change in the area.

Thanks to the analysis of small vertebrates and molluscs from seven archaeological and paleontological sites in the Kraków-Częstochowa Upland we now have a clearer picture of what happened between 20,000 and 8,000 years ago in southern Poland:

We can start from the moment, around 20,000 years ago, when tundra dominated over a few forests, the latter probably formed around rivers or in other favourable areas. Let’s imagine a landscape similar to today’s northern Scandinavian region. The temperatures were extremely cold, with values similar to those of Oulu in northern Finland. Not so far from Ojców, around 200 km further north, the great Scandinavian Ice Sheet almost reached the modern-day area of Warsaw.

Around 14,500 years ago all the worldwide data show a period of global warming. Unfortunately, in our data this moment is not so well registered because there are some gaps, but we can suppose a gradual temperature increase, with the retreat of the northern ice sheet, while the landscape equilibrium continued for a few millennia. Then, between 11,700 (or shortly before) and 9,000 years ago, the climate values (temperature and precipitation) reached a level favourable for the advance of boreal forests but with open meadows still present. In that period, the climate in Southern Poland reached values similar to the ones of Suwałki.

This moment was very short, probably lasting only a few centuries. Shortly after, the climate data show a quick temperature increase reaching values similar to those nowadays. The boreal forest was quickly replaced by a mixed one comparable with the Białowieża forest. This kind of landscape probably persisted until the arrival of the first farmers.

© C. Berto, the right-hand image was modified from the original found on Wikimedia commons (© Abyssal)

CC BY-NC-SA 4.0 licence

And what happened to the little rodents? Well, as usual they adapted to the changing climate. Some species had a strong population, like the bank vole (Clethrionomys glareolus) or the European pine vole (Microtus (Terricola) subterraneus) which love the forest shady areas. And, year after year, new species replaced the old ones because new ecological niches formed thanks to the global warming: for example the dormouse (Glis glis) and the hazel dormouse (Muscardinus avellanarius), both adapted to closed broadleaf forests, arrived in the Ojców area.

In contrast, some species migrated northwards following the suitable cold conditions and reaching new available areas such as the Scandinavian peninsula. Some others probably became extinct, unable to adapt to the new world, like the Lasiopodomys anglicus, the unfortunate hero of our little story.

Author:

Claudio Berto – palaeontologist; his greatest passion are small quaternary mammals (rodents, insectivores and bats from the period spanning from 2.6 mya to modern times). His main research interests focus on reconstruction of the past climate and natural environment on the basis of remains from archaeological sites. He is also interested in evolutionary trends in populations of small mammals.

He has published papers about the remains of mammals from the Apennine Peninsula and Kraków-Częstochowa Upland.

This text was funded by a project entitled “From caves to public: A series of popular science articles published on the archeowieści.pl blog, showing a multidisciplinary approach in archaeology, based on the results of our researches in the Ojców Jura” from the Inicjatywa Doskonałości – Uczelnia Badawcza programme. Research on the caves of the Sąspowska Valley was funded by the National Science Centre, project: SONATA BIS 2016/22/E/HS3/00486.

Reference: Berto, C., Szymanek, M., Blain, H.-A., Pereswiet-Soltan, A., Krajcarz, M., Kot, M., 2022. Small vertebrate and mollusc community response to the latest Pleistocene-Holocene environment and climate changes in the Kraków-Częstochowa Upland (Poland, Central Europe). Quat. Int. 633, 6–25. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.quaint.2021.09.010

Editing: A.B.

Proofreading: S.A.

Cover: E. A. Büchner, Nauchnye rezulʹtaty puteshestvīĭ N.M. Przhevalʹskago po T͡Sentralʹnoĭ Azīi, izdannye Imperatorskoi͡u akademīei͡u nauk. Tom I. Mammali, G. Mützel, Microtus gregalis from Plate on the page 267, Public Domen, editing Archeowiesci