Caves have been an object of human fascination since the dawn of time. These mysterious, closed spaces served various functions in the past – from temporary shelters or flint workshops to places of burial or worship. Human history is recorded here in long stratigraphic sequences, with each layer being a part of a long-forgotten story. We try to read these stories and reconstruct the lives of ancient people. Usually, we use for this purpose artefacts: objects left or lost by the former inhabitants of the caves or by people visiting them. Sometimes our reconstruction is not clear – there are too few objects or they are too well hidden. However, every human activity leaves behind something more than artefacts. It leaves behind chemical traces. We just need to learn to read them properly.

Searching for invisible traces

Over the last few months, our team has been publishing in Archeowieści the results of an already completed project regarding the caves of the Sąspowska Valley. The return to the old sites showed how much progress has been made in archaeology over the last 50 years and how much new information we can still obtain. These data allow us, for example, to reconstruct the paleoenvironment and paleoclimate in which humans lived in the past. However, the most difficult aspect turned out to be obtaining new information about human activity in the caves. We have already analysed all available archaeological material – both the old material that has been lying in dusty boxes for years, and that coming from new research. However, we still felt unsatisfied. So we turned our attention to cave sediments. During our research, we collected many sediment samples, and some of them were used for specialized analyses: paleogenetic or paleoenvironmental. However, we preserved some more samples in case we came up with a new idea or got struck by further inspiration.

This particular inspiration has already appeared in 2020 and was turned into my doctoral project, and then later into the Preludium project, financed by the National Science Center in Poland. The name, a bit lengthy, is Chemical Traces of Human Activity in Caves of Polish Jura. Use of selected lipid biomarkers analysis and PAHs analysis in sediments from archaeological sites.

Recently, together with my team, I published the concept and preliminary results of the project – based on the example of a particulary intriguing site – in the Project Gallery in the “Antiquity” journal. However, before I tell you about Łabajowa Cave, the intriguing cave included in the project, I would like to explain in more detail what looking for invisible human traces actually means and how I plan to find them.

© M. Kot, licensed under CC BY-NC-SA 4.0

So let’s start from the beginning: why cave sediments? Traditionally, confirmation of human presence occurs after finding a collection of artefacts, or traces of hearths, which in the context of caves usually clearly indicate the presence of humans. What if we don’t find such traces? What if we find artefacts, but these are just a few flint chips? There may be several explanations for such a situation:

- Maybe we opened the trench in the wrong place? It should be noted that excavations in caves are very expensive and time-consuming: it requires wet-sieving (i.e. rinsing of sediments using sieves of various mesh sizes) of all sediments from the trench, sometimes the installation of lighting, platforms, formwork and other safeguards necessary to preserve safety and comfort while working. This often leads to opening rather small trenches. At the same time, we want to preserve part of the original site for future generations of archaeologists, when the development of research methods will enable us to obtain even more information.

- Maybe the site was explored many years ago and we lost the artefacts or their context? This situation occurs at many sites of the Kraków-Częstochowa Upland, where caves have been explored since the end of the 19th century. Unfortunately, the research and documentation methods of those times were completely different from today. The turbulent war periods were also not conducive to the preservation of information about old excavations, and many artefacts were lost.

Fortunately, there is no need to lose hope. Even when we do not discover an artefact collection, the ancient people staying in the cave must have left some other, invisible traces. These traces may be hidden in cave sediments.

Searching for methods of reading invisible traces

The question that should be asked is: what methods can we use to discover something new about human activity in caves? After conversations with specialists (Prof. Maciej Krajcarz and Prof. Małgorzata Suska-Malawska), I chose a few promising techniques:

- lipid analyses – faecal sterols and bile acids,

- analysis of burning markers – polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons (PAHs)

- elemental analysis – organic carbon, nitrogen and phosphorus.

We will focus on the first two groups, as they are the most important to us. We decided to evaluate their potential and see what information we could obtain about people and animals visiting the caves in the past using the aforementioned analyses. Our training grounds were caves of the Kraków-Częstochowa Upland, specifically seven sites:

Sąspowska Zachodnia Cave, Bramka Rockshelter, Ciasna Cave, Biśnik Cave, Shelter in Smoleń III, Łokietka Cave and Łabajowa Cave.

Each site has a unique set of problems to solve and questions we hope to answer. But let’s stay with the methods for a moment.

©N.Gryczewska, licensed under CC BY-NC-SA 4.0

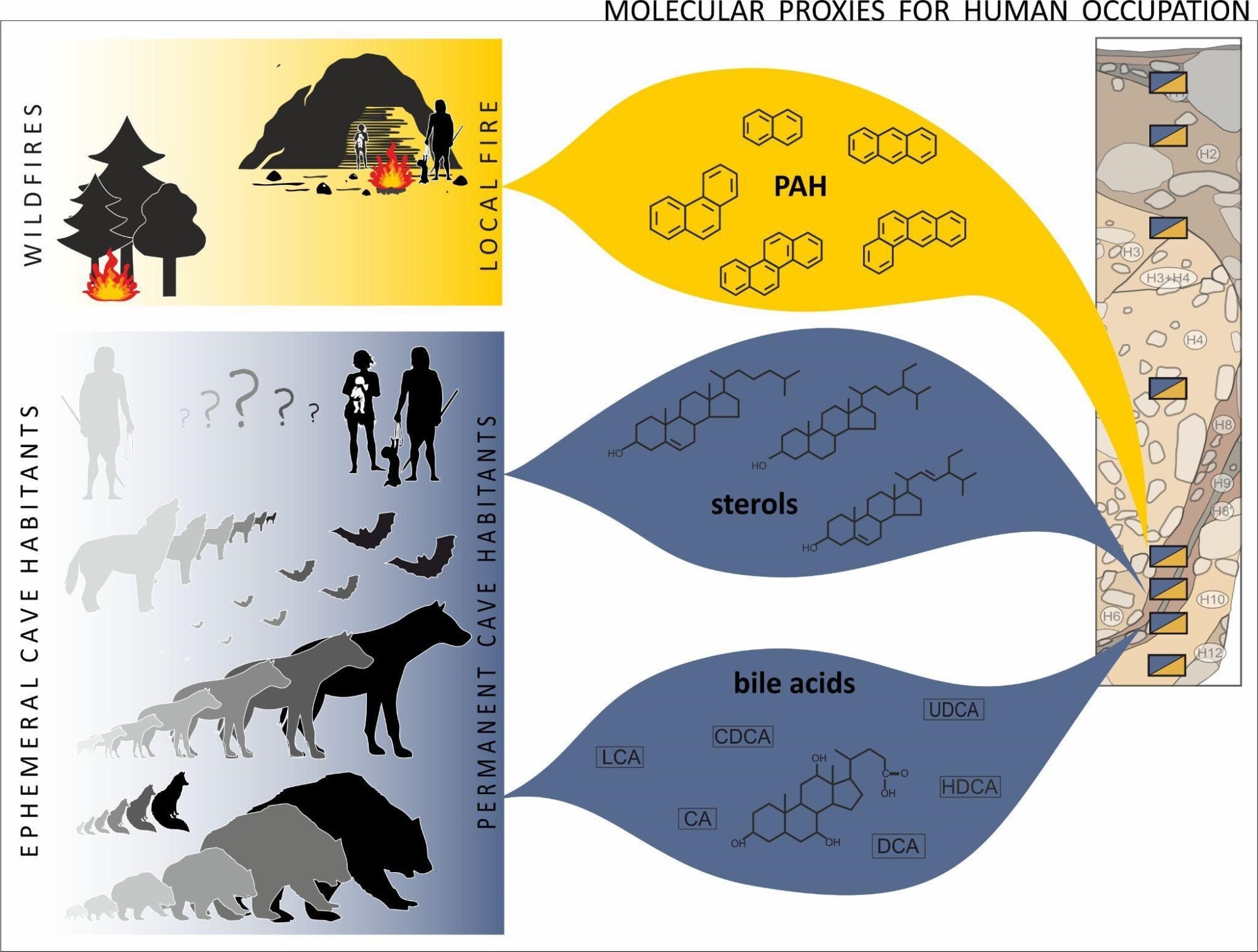

Faecal sterols and bile acids are two groups of compounds that can be found in faeces. Sterols can be divided into animal sterols (the most famous of them is cholesterol), plant sterols and those found in mushrooms. They have various functions, for example, they form part of cellular membranes. These compounds can be absorbed with food or produced in the body, where they are transformed through metabolic processes and then excreted within faeces. Bile acids are produced in the digestive system and also leave the body along with sterols.

Which sterols and bile acids, and in what proportions, are found in faeces depends on the diet and metabolism of a given species, so there are differences between animals (herbivores will have dramatically different compositions of sterols and bile acids). Most importantly, humans also have a very distinctive profile of sterols and bile acids.

The advantage of these compounds from the archaeologist’s perspective is that they are insoluble in water, preserve well in sediments for thousands of years and undergo only minor changes in post-depositional processes (thanks to many years of experiments conducted on the preservation of sterols and bile acids in the ground, we know what changes they may undergo over time and we can take this into account in our interpretations). Therefore, these compounds have been successfully used in archaeology for many years. They are useful in examining latrines and identifying sewage channels, in determining the extent of ancient fields (if they were fertilized with animal or human excrements) and even in identifying species of farm animals at a site. In the last few years, archaeologists have even gone a step further and begun analysing sterols, often together with bile acids, in lake sediments to trace the appearance of humans and domesticated animals in a given area, i.e. around the studied water reservoir.

The second group of compounds that are the subject of my project are Polycyclic Aromatic Hydrocarbons (PAHs). Nowadays, these compounds are one of the indicators of air pollution, because they are produced during the combustion of fossil fuels, but also by volcanic eruptions or cigarette smoking. In archaeological research, however, they can be used to identify traces of fire, and sometimes also to determine what material was burned (coniferous wood, hardwood, or perhaps dried animal excrement). PAH analyses can be used to determine whether the fire was burning close to where the sample was taken or whether the compounds were blown in from a distance. In the context of a cave, a fire originating nearby is almost certainly evidence of human presence and activity. In pre-industrial times, traces of burning distant from a site are either from natural forest fires or forest fires caused by humans, for example as a method of preparing land for cultivation.

Source: Antiquity, licensed under CC BY 4.0

This means that we can use analyses of both lipids and burning markers to confirm whether people (in the case of sterols and bile acids, also animals) have stayed in the cave in the past. Moreover, we can confirm this even if there are no traces of human presence visible to the naked eye, such as lost objects or skeletal remains. In combination with other methods already commonly used in cave archaeology (dating, paleoenvironmental reconstruction, etc.), we want to create the most complete picture of human life and activity in the past. All these compounds can be analysed using a gas chromatograph coupled with a mass spectrometer.

The mystery of Łabajowa Cave

After this very long introduction, we can now focus on the research in Łabajowa Cave, presented in a new article in the journal “Antiquity”. This is an interesting case of a site that was discovered and explored at the end of the 19th century and then completely forgotten. This cave attracted our attention again when, during the previously mentioned research work in the Sąspowska Valley, we were looking through literature about the old excavations in the nearby caves. Thanks to a short mention in Ferdinand Roemer’s publication from 1883, we learned that a set of artefacts and traces of a fireplace has been found in Łabajowa Cave.

© K. Lorek, licensed under CC BY-NC-SA 4.0

We have been interested in Roemer, a palaeontologist working at the University of Wrocław at the end of the 19th century, for a long time. In the second half of the 19th century, in several caves of the Kraków-Częstochowa Upland, cave sediments were exploited and sold as natural fertilizer. The demand on the agricultural market for cave sediments resulted from their high phosphorus content, which was related to bat guano and… the remains of animals that died in the cave over the millennia. During this extraction of sediments, the remains of extinct animals and human products, such as tools and decorations made of flint, bone, clay and metal, were found. Roemer managed to obtain some of these finds and thus began his collection of materials from the caves of the Polish Jura. At the same time, fascinated by the discovered materials, he initiated amateur archaeological excavations in several caves in the region. He hoped to obtain more bones and artefacts. Łabajowa Cave was explored on his orders.

Unfortunately, Roemer’s collection was dispersed and today only a fragment of it is in the Archaeological Museum in Wrocław. The artefacts had been mixed; some had preserved records with signatures, and some were signed in ink directly on the artefact. We recognized some of them: their drawings had been published in Roemer’s article from 1883. To our surprise, among the flint tools, we discovered a Jerzmanowician blade labelled as coming from Bembel Hohle (the former name of Łabajowa Cave). Roemer’s publication did not mention such a blade from Łabajowa Cave! The Jerzmanowice blade is a type of tool characteristic of the enigmatic archaeological culture from the turn of the Middle and Upper Paleolithic – the Jerzmanowice culture. Enigmatic because we are not sure whether its creators belonged to the Homo sapiens or Neanderthal species. We also know just a few Jerzmanowician sites. We have already written about this in more detail in the context of research in Koziarnia Cave, so let’s just recall the most important points. This culture was distinguished based on finds from Jerzmanowicka Cave (today known as Nietoperzowa Cave), located only 300 m in a straight line from Łabajowa Cave! Artefacts from Nietoperzowa Cave were also in Roemer’s collection. So have we found a new site of the Jerzmanowice culture? Could this just be a mistake when the discoverer labelled the blade?

This mystery prompted us to carry out excavations in Łabajowa Cave, led by Dr hab. Małgorzata Kot. To our surprise, we did not discover any artefacts in situ, although the excavation was located right next to the 19th-century trench, which is still visible in the field in the form of a depression. Were we just unlucky and that’s why we missed the artefacts? Or maybe all the material remains were discovered in the 19th century? It was then that we decided to turn to more unconventional methods that could confirm the presence of humans in Łabajowa Cave – analyses of sterols, bile acids and PAHs. For more details about the mystery of Łabajowa Cave, we encourage you to read our new article. More secrets connected to Łabajowa Cave and other caves included in the project will be revealed soon.

Literature:

Chemical research related to the project is carried out at the Laboratory of Biogeochemistry and Environmental Protection at the Center for Biological and Chemical Sciences of the University of Warsaw.

Research on chemical traces in the caves of the Kraków-Częstochowa Upland is financed by the National Science Center in Poland (grant no. 2021/41/N/HS3/02369). Excavations in Łabajowa Cave were financed by the National Science Center grant No. 2016/22/E/HS3/00486, the ongoing paleoenvironmental and chronostratigraphic analyses are financed by the National Science Center grant No. 2020/39/B/HS3/00932.

This article can be reprinted free of charge, with some photos, and with the source indicated.

Author: Natalia Gryczewska