How can we know an ancient prison when we see one? The question is a bit tricky, because prisons have proven challenging to identify in the archaeological record. One might ask, after all, aren’t they just rooms like any other rooms: four walls, single entry and exit, and a door with a locking device? What makes them different from other spaces?

While there are certain outliers, the traditional understanding has been that prisons are generic rooms and hard, if not impossible, to distinguish. In fact, an archaeologist of the stature of Luke Lavan has recently claimed:

“Of prisons we know little. We have no securely identified architectural evidence.”

(Lavan 2007: 121)

While this comment is incorrect, it does reflect the state-of-the-field in archaeology when it comes to identifying prisons. At a different level, while a few (and growing) number of prisons have been identified by excavators during the course of the 20th century, many experts would admit that they have no idea what a Roman prison looks like, which reflects the lack of anything like a typology of ancient Roman prisons.

Materiality of incarceration

My research team and I aim to address this particular issue in the project “Materiality of incarceration in Mediterranean Antiquity” . We have demonstrated in recent publications that it is possible to securely identify prisons in the archaeological record as well as catalogued a significant amount of other material culture related to incarceration (for example: several paintings of prison scenes from Pompeii). The project’s hypothesis, then, is that incarceration remains hidden in the archaeological record, waiting to be exposed to scrutiny and integrated into our sense of the human past. The project aims to survey circa 25 ancient prisons and other sites of incarceration, producing high-resolution 3D models of each site. With such survey work and 3D models in place, team members will then study the different types and patterns of public prisons and other sites of incarceration.

Public Domain

But, this still doesn’t answer the question, which is the premise of the project: is it possible to securely identify a prison in the archaeological record; and if so, how can we identify a prison? To know a prison “when we see one” first involves securely identifying several prisons and studying their features. But what signs might definitively confirm a place as a prison as opposed to another type of place (for example a cistern, a treasury, a storage room, etc.)? There are, as it turns out, a few secure diagnostic features.

Known ancient prisons

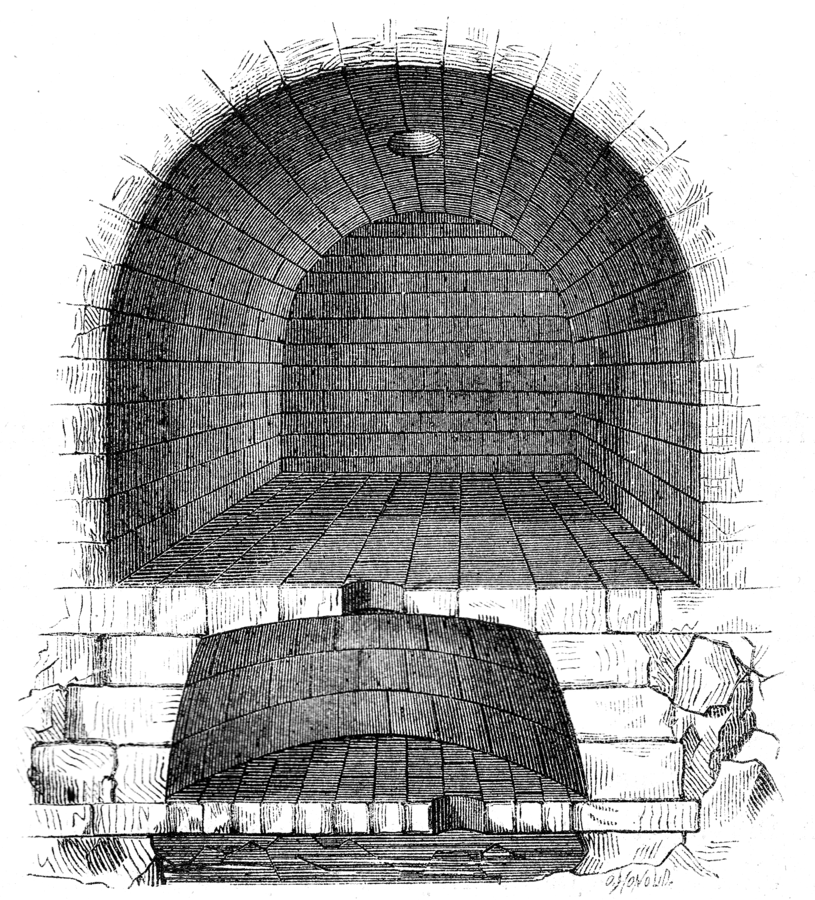

The most well-known prison of the ancient world, the Carcer-Tullianum, is identified primarily through the correlation of multiple ancient sources, describing its location and architectural structure, to an existing archaeological site today . Yet this is not the only literary description of an ancient prison. Plutarch describes the prison of Messene during the time of Philopoumeni, which he says was nicknamed “The Treasury” . Archaeologists uncovered a site that neatly matched Plutarch’s description of the space, and have identified it as Philopoimen’s prison in Messene.

Another strong diagnostic feature of a prison is the presence of graffiti inside a secure (and often underground) space. Graffiti were instrumental in the identification of the Roman military prison in Lambaesis . Graffiti indicate that someone spent substantial time in the space, who had only rudimentary tools with which to mark the dense sandstone walls. Nowhere is the use of such graffiti clearer than in the prison in late Roman Corinth, in which prisoners scratched on the floor tiles things like:

“get me out of this lawless place”

and

“God, show no mercy to the person who threw us in here”

(Larsen forthcoming).

Another clear diagnostic feature of a prison is the presence of stocks, anchors in the walls, and/or other shackling technologies affixed in a space, especially when we can discern that the shackles were used on humans. For instance, in the Villa of Mosaic Columns in Pompeii, there is a series of underground chambers in which two stocks were affixed to the room which still held, at the time of excavation, two tibia (lower leg bones) inside. This was not a public prison, to be sure, but it was most certainly a site of incarceration. From a slightly different angle, the prison for the condemned was identified both by the presence of graffiti as well as dozens of anchors cut through the plaster into the drywall for the purpose of shackling. They show signs of wear and tear, and graffiti are placed immediately around the places of shackling .

My innocent search for something just took a rather macabre turn.

On 17th Oct 1905, a skeleton of a slave was found in a cellar in the Villa of the Mosaic Columns, #Pompeii that had iron fetters; 3 rings around each ankle which were clamped & pinned to the ground by an iron rod. pic.twitter.com/I2vW0QhJLm— Dr Sophie Hay (@pompei79) August 29, 2022

Cistern, treasury, or a prison?

Sometimes a space is clearly either a prison or some other specific space, and our research team is currently looking to develop other methods to disambiguate such spaces, especially cisterns, treasuries, or other underground strongrooms. The question is what helps to diagnose a cistern from a prison, or a treasury from a prison? One idea would be through the tracing of urine residue within a space, as this would indicate prolonged human occupation, such as one would not expect to find in a cistern or treasury. Another diagnostic feature relevant for future excavation is signs of human occupation, such as a surplus of remains of lamps or olpes, such as was found in the secure space underneath the tribunal in Roman Corinth . Essentially, one distinction between prisons and cisterns, on the one hand, and treasuries, on the other, is that humans inhabited them, and had need for certain necessities such as eating, light, urination, defection, etc. If we find significant evidence in a space that is either a prison or a cistern/treasury, such evidence might tilt the scales of interpretation.

Once a significant number of securely identified sites are identified, we will be in a position to develop a more advanced typology of ancient Mediterranean (though, admittedly, mainly Roman) prisons. Thus far, other common (though not necessarily diagnostic) features would be small windows opening onto the public street, large enough for an arm to pass through food or letters, an entrance to an underground space through a manhole above secured by some kind of lid, or proximate connection to the site of trial immediately above. A typology of ancient Mediterranean prisons would enable us to distinguish the occasional “underground strongroom beneath tribunal”, once we have developed a constellation of other known features.

Breaking out of the old prison model

While often thought to be a globally urgent and uniquely modern problem, prisons and incarceration must have been a ubiquitous part of everyday life in the ancient Mediterranean world. The problem is that the materiality and archaeology of incarceration has almost entirely escaped the grasp of modern researchers. We hope that our project’s impact will be to disrupt a broad century-old scholarly consensus regarding the relative absence of the prison from the ancient world and its birth in early modern Europe and the US , with the potential to shift central assumptions in the ancient Mediterranean world, not only opening up new lines of inquiry in my field of early Christianity — so full of sources on incarceration — but also ancient Judaism, classics, early Islam, and medieval Europe.

You can hear more about ancient prisons during an open lecture by Dr Matthew Larsen this Friday (8.03.2024) at 13:15, Faculty of Archaeology, University of Warsaw, room 2.11

This article can be reprinted free of charge, with photos, and with the source indicated

References: Lavan 2007: 121 Fortini 2022 Plutarch, Philopoemen 19–20 Themelis 2010: 122–124 Letteney and Larsen 2021 Larsen forthcoming summer 2024 Notizie degli scavi 1910: 259–60 Dadea 2006: 84–85 Scotton, Corinth 22, p. 217–18 Durkheim, Mommsen Foucault

Author:

Matthew David Larsen – Associate Professor of New Testament at the University of Copenhagen. He works on the cultural and material histories of ancient Christian communities from the first to fifth centuries, with specialization in archaeology, material culture, and carceral studies. Prior to Copenhagen, Matthew served as a faculty member at Yale University and Princeton University, where he was in the Princeton Society of Fellows. He is the author of Gospels before the Book (Oxford University Press, 2018), which won a Manfred Lautenschlaeger award, and an Italian translation of which is forthcoming (with Editrice Queriniana). His research is published in Hesperia, the Journal for the Study of Judaism, the Journal for the Study of the New Testament, the Journal of Early Christian Studies, Studies in Late Antiquity, and his scholarship has been featured in The Daily Beast, CHOICE, and Christian Century. He is currently completing two book manuscripts: a monograph on early Christians and incarceration and an interdisciplinary book overviewing the institution of incarceration in Mediterranean antiquity.

Editor: J.M.C.

Proofreading: S.A.

Cover: Illustration generated in Midjourney, edited by K.K.

Promt: man in shackles in an ancient roman prison cell