I turn a tiny flint fragment in my hands. I can see that one of its sides was very accurately shaped with small percussions in order to make a triangular tool. It is slightly more than a centimetre long. I need to use a magnifying glass to see its details. Who made it? When? Was it made by the last European hunters? Why did they leave it in a cave?

Climate change twelve thousand years ago

The Pleistocene (Ice Age) finished 11700 years ago, when the great ice sheets melted down. Only 25 thousand years ago these ice sheets extended to Warsaw, Hamburg and Bristol, which means they covered a big portion of northern Europe. The slow melting of the ice sheets, described as the Late Pleistocene, was not an uninterrupted process. The cold water melting from the glaciers accumulated at their periglacial zones and spilt over to the closest ocean from time to time, cooling one part of the world or another, or diverting warm ocean currents. Still, the climate warmed steadily. The glaciers slowly melted and the cold mammoth steppe replaced the semi-open ecosystems of the tundra, covered with sparse trees, mainly pines and birches, and then gave way to forests. Initially, they were coniferous forests, like the taiga that we know from modern times. Later on, when the climate became more favourable, the first broadleaf trees appeared, and consequently, the mixed coniferous forest. A new epoch began – the Holocene.

© M. Kot, CC BY-NC-SA 4.0 licence

These changes had very obvious consequences for the last reindeer hunters, whom we call Final Palaeolithic hunters and who lived in this part of Europe. They had to either follow the reindeer herds, migrating further and further north, or stay and adapt to life in the ecosystem of the forest, very different from what they were used to. Those who opted for the latter are the protagonists of this story.

The last European hunters

And so the open space of the tundra, where it is very easy to see the game or the closest limestone rocks bearing valuable flint, or even a source of water, is gradually replaced with the dark wet forest. Very thick primeval forest, where you can barely see pieces of heaven and guess whether you can expect rain soon. You look around and only see a few closest trees. The ground is covered with thick understory. You could stumble over a piece of flint and not notice it. You can hardly know your way. Where should you get raw material to make your tools? How to get to the nearest water source? How to return without losing your way?

Survival in the closed space of the forest required a completely different lifestyle and different weapons for hunting. The forest is full of animals, but these are not great herds of reindeer, which could be hunted with the same type of points all the time. The life in the forest calls for preparation for hunting any type of game – birds, hares, roe-deer or aurochs. However, each of them is hunted in a different manner. But how to make all these types of weapons if it is almost impossible to find flint? How, being a nomad, to move to different places if discovering new areas takes much more time?

© M. Bogacki, CC BY-NC-SA 4.0 licence

All these questions appear in the minds of archaeologists. The Final Palaeolithic hunters did not respond verbally, but with their everyday activity. We can see these gradual changes in their lifestyle, diet, social structure or manner of production of tools. We track them and try to describe them. The changes are so significant that we identify a new epoch. Therefore, after 2.5 m years of stone tool production, the Old Stone Age (Palaeolithic) finishes and a new one begins: the Middle Stone Age that we call the MESOLITHIC.

Observation of these social and cultural changes taking place in Europe in the Late Pleistocene and Early Holocene is fascinating. The more so because at the same time other Final Palaeolithic hunters in the Near East – in response to climate change and its warming, resulting in a decrease in humidity and consequently in the amount of available food there – began to control herds of animals, which was the first step to their domestication. These hunters gradually became pastoralists, and the gatherers – farmers. Thus in the Near East the Palaeolithic does not end in the Mesolithic, but right away in the Neolithic, that is, the New Stone Age. Five thousand years will pass before these first farmers set off from the Near East and populate whole Europe. But throughout these millennia the last hunters and gatherers of our continent – the Mesolithic hunters – will live in the thick primeval forests covering almost whole Europe.

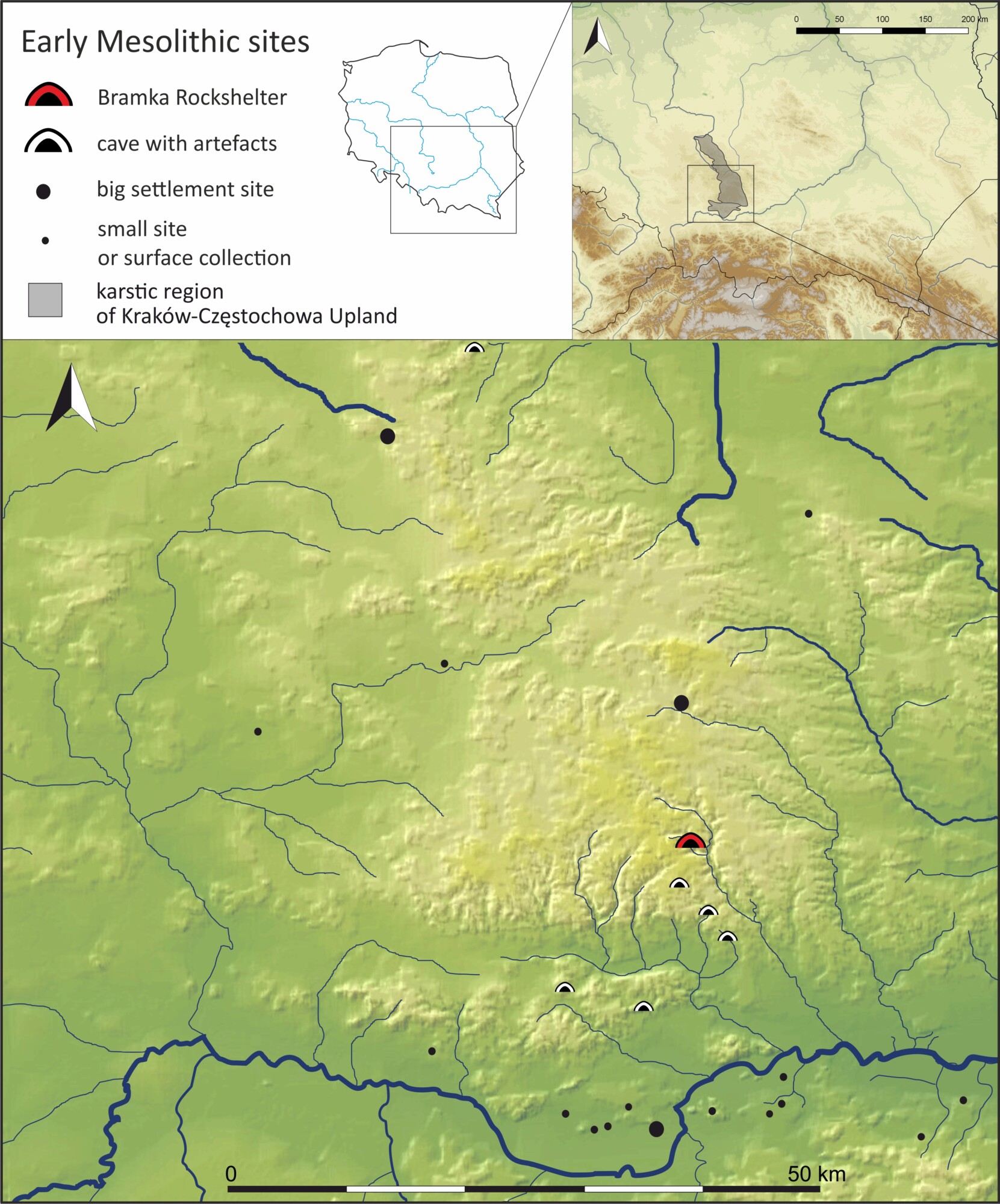

Bramka Rockshelter

A forest interspersed with countless lakes and rivers, still full of cold post-glacial waters, is their home. Lakes and rivers in this post-glacial landscape become the only areas where the eye can scan a larger space. On the lake shore you can see some sky and look around at last. Thus it is not surprising that humans preferred shores of water reservoirs for their camps. Water becomes their element anyway. They use boats (dugouts) to travel over the lakes to catch fish with nets made of plant fibre or with fish traps. We find bone hooks and harpoons at Mesolithic sites. The hunters quite likely made most of these tools of wood, but such specimens rarely survived to our times. Wood is abundant – it is easy to source it to make dugout boats, oars, or build a hut. It is not necessary to struggle with building bone shelters, like in the Pleistocene. Caves cease to be needed for camps. There are very sparse Mesolithic artefacts from caves located in the Polish territory. They are evidence for short visits, possibly during hunting trips.

© M. Kot, CC BY-NC-SA 4.0 licence

But there is an exception – Bramka Rockshelter. Its picturesque rock window, slightly more than 3 m high, together with Małe and Wrota Rockshelters located nearby, is a relic of an old cave network that collapsed long ago. Only these three small rockshelters have survived to this day, and Bramka is the biggest. Its side is situated along the steep slope of the Sąspowska Valley: this is why the remains connected with human presence throughout its history were prevented from being washed by rains down to the bottom of the valley, but instead accumulated in a small depression below the rock window and left a mark of the unique history of occupation of the site.

The research conducted by our team at this site – and before us by Professor Waldemar Chmielewski – indicates that 9700 years ago a group of hunters associated with the Early Mesolithic Komornica culture arrived at this rock shelter. At the moment it is one of the oldest relics of the Mesolithic peoples in Lesser Poland and Cracow-Częstochowa Upland. These people have just arrived in the area: there are no remains of similar settlement activity in this region. Most likely, they do not know the area, or perhaps just the opposite – they know it perfectly well. But we will look at that in a moment. They select Bramka Rockshelter for their camp. Why this site and not one of the many caves located in the valley? The shelter is situated very high, you see the whole valley from the top of the rock. Apart from that, when both entrances are shielded, it can be converted into something like a hut covering about 12 m2.

© Archive of the Faculty of Archaeology UW, CC BY-NC-SA 4.0 licence

A long-term camp or a workshop?

The Mesolithic hunters arrive at the cave site, but not to spend the night and then move on. Such temporary camps are associated with characteristic remains: a few abandoned tools – mostly elements of repaired hunting weapons, sometimes a few flakes removed from tools made on the spot. That’s it. In this particular case, there are over 7000 Mesolithic flint artefacts, recovered from the surface of roughly a half of the site. This enormous concentration of artefacts is evidence for a very intensive exploitation of the site. But what might have been its function? This is where analysis of the artefacts could help us. If we find a lot of tools at a site, we can usually suggest a long-term camp. However, if, as in the case of Bramka Rockshelter, tools are just a minor fraction while the waist from production of tools or blanks is the majority, this is what we call a flint workshop- place devoted to tools production. This is the function that we attribute to Bramka Rockshelter. This means that the real objective of the trips that the Mesolithic hunters made to the Sąspowska Valley was probably sourcing of flint, which can be found in this region along the valley, with its greatest abundance in this particular area. The path to the cave is still practically paved with big lumps of flint. Almost all of the artefacts were made of this type of flint.

© M. Kot CC BY-NC-SA 4.0 licence

Did they come here just once, or did the rockshelter witness their successive visits to the valley to procure flint? It is difficult to answer this question. Interestingly, the Sąspowska Valley is located halfway between two big and well-researched Early Mesolithic camps from that period – Ściejowice and Glanów sites. The radiocarbon dates from Bramka Rockshhelter overlap with the earliest relics of settlement activity at Glanów and are slightly older than those from Ściejowice. Does this mean that Bramka Rockshelter is evidence for trips for flint made by a group of Mesolithic hunters living permanently in the vicinity of these sites? Or perhaps it was a regular stopover on the way communicating these two camps?

Mesolithic microlithization of tools

I look at the tiny flint triangle again. It is one of 15 found at the site. Apart from it – very few other tools. These sparse tools were discovered in association with thousands of flakes from different phases of shaping of cores and then removal of microblades. The cores from which the microblades for production of the triangles were removed are not much more than 3 cm long. Everything is so tiny. Why? Did the shortage of flint raw material and difficulties in its sourcing force the change in production of tools and this unusual microlithization of tools, characteristic of the Mesolithic? Most likely – at least partially – it was so, but with the passage of time it must have become a custom and tradition: flint in Bramka Rockshelter was abundant, but despite that, the hunters kept making only the microlithic tools. And those triangles – what was their function? They served as inserts for weapons, probably arrows. Attached at the tip, the triangle was the point, with another one or more attached at the sides to make barbs. It was an easy solution for making various types of arrows for hunting different species of game with just one type of tools. After all, Mesolithic hunters had to be flexible to adapt to the diversity of forest ecosystem.

© M. Kot CC BY-NC-SA 4.0 licence

This article can be re-printed with photographs free of charge provided that the source is cited

Author: Małgorzata Kot

This text was funded by the project entitled “From caves to public: A series of popular science articles published on the archeowieści.pl blog, showing a multidisciplinary approach in archaeology, based on the results of our researches in the Ojców Jura” from Inicjatywa Doskonałości – Uczelnia Badawcza programme. Research on the caves of the Sąspowska Valley was funded by the National Science Centre, project: SONATA BIS 2016/22/E/HS3/00486.

References:

Jaskinie Doliny Sąspowskiej. Tło przyrodnicze osadnictwa pradziejowego. Praca zbiorowa. Pod red. W. Chmielewskiego, Warszawa 1988, Prace Instytutu Archeologii UW.

Kot M., Gryczewska N., Szymanek M., Moskal del-Hoyo M., Szeliga M., Berto C., Wojenka M., Krajcarz M., Krajcarz M., Wertz K., Fedorowicz S., Jaskulska E., Pilcicka-Ciura H. (2022), Bramka Rockshelter: An Early Mesolithic cave site in Polish Jura. „Quaternary International” 610, 44-64, doi: 10.1016/j.quaint.2021.08.015

Project website: https://www.dolinasaspowska.uw.edu.pl

2 Replies to “Bramka Rockshelter – what the last European hunters did in a cave”