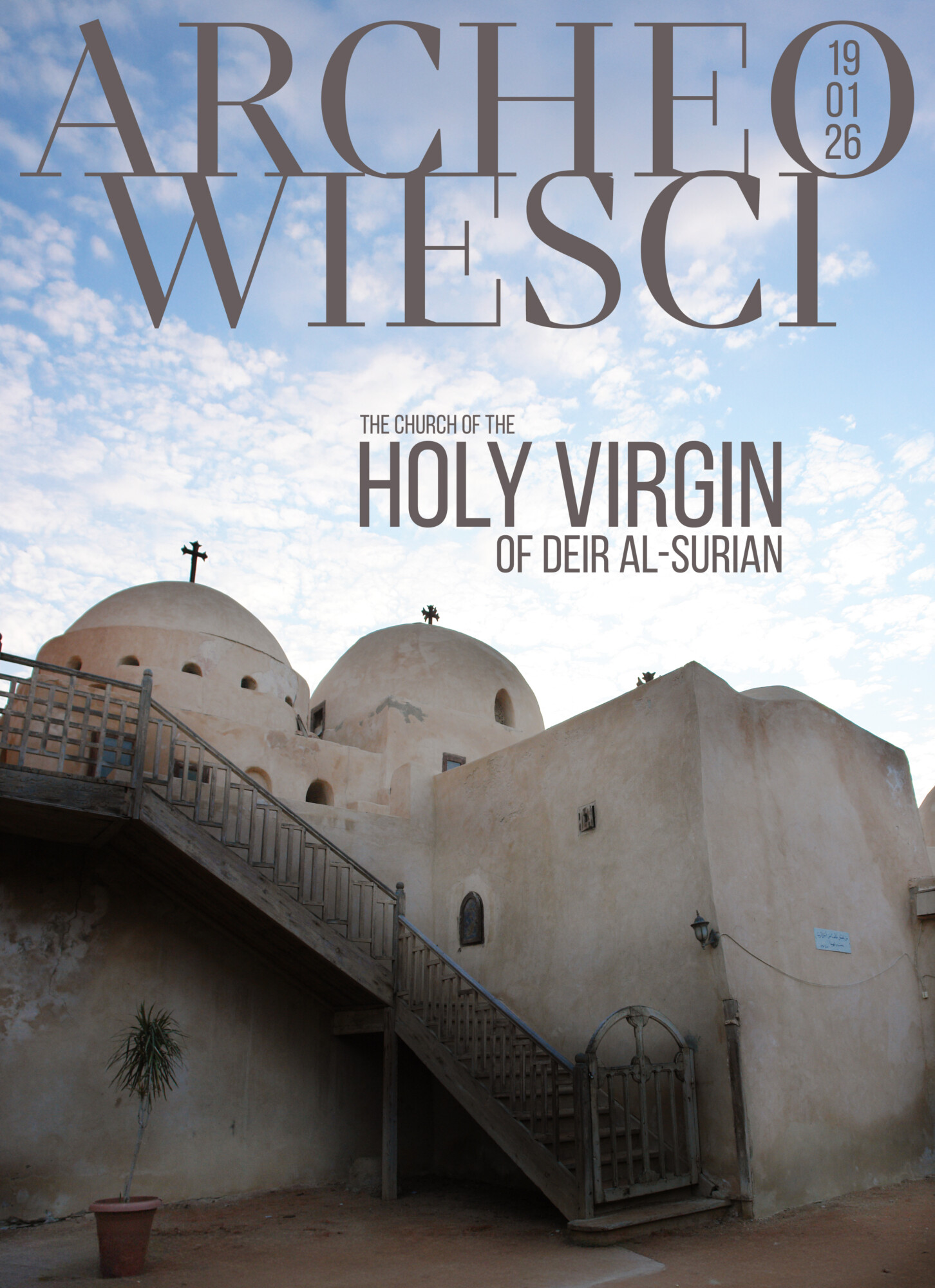

Deir al-Surian is located in the geological depression of Wadi al-Natrun, west of the Nile delta, a region known as Sketis in Late Antiquity. Its church, dedicated to the Holy Virgin, has been in continual use since its construction in the 7th century AD. Between the 9th and 16th centuries, a mixed Syriac-Coptic community celebrated in the church, and its architecture, paintings and inscriptions testify to the cultural exchange between the two groups.

Deir al-Surian is located in the geological depression of Wadi al-Natrun, west of the Nile delta, a region known as Sketis in Late Antiquity. Its church, dedicated to the Holy Virgin, has been in continual use since its construction in the 7th century AD. Between the 9th and 16th centuries, a mixed Syriac-Coptic community celebrated in the church, and its architecture, paintings and inscriptions testify to the cultural exchange between the two groups.

Coptic Origins

Deir al-Surian belongs to the oldest still-inhabited monasteries in Egypt (and thus in the world) and is located in an area where the history of monasticism started. The monastery was founded at the beginning of the 6th century, when a theological conflict over the corruptibility of the body of Christ divided the community of nearby Deir Anba Bishoi, and a group of monks who considered themselves orthodox moved out and founded a new monastery under the name of the Monastery of the Holy Virgin of Anba Bishoi.

© Deir al-Surian Conservation Project

Syriac presence

Until the end of the 8th century the monastery was inhabited by Coptic monks. Sketis attracted not only visitors from abroad, but also monks from other regions, such as Nubia, Ethiopia, and Palestine, who settled here and either started their own monastic communities or joined Coptic monasteries. Possibly already by the end of the 8th century monks from Syria were present in the Monastery of the Holy Virgin of Anba Bishoi. Around AD 800, the monastery was seriously damaged by a Bedouin raid. Soon after that, according to inscriptions found in the church, the damage was repaired and the monastery expanded through the joint efforts of Syrian and Coptic monks. From that time onwards, until the 16th century, a community of Syrian monks has lived here in cohabitation with Coptic monks, and this was the origin of the unofficial name of the monastery (Deir al-Surian means Monastery of the Syrians). During this period, the monastery amassed exceptional wealth and was an important crossroads for Coptic and Syriac Christian cultures. Especially under the abbacy of Moses of Nisibis (first half of the 10th century), the monastery flourished to an unprecedented extent. He commissioned major renovations to the church and added a large number of manuscripts to the library, making it the largest collection of Syriac manuscripts in the Middle East at that time. This collection is now scattered between the British Library, the Vatican, and St. Petersburg.

© Deir al-Surian Conservation Project

The paintings

The oldest and most important church in the monastery is the one dedicated to the Holy Virgin, built around the middle of the 7th century. This church still reflects the cultural wealth of the monastery in past centuries, as has been made clear by discoveries in recent decades.

In 1991, after a fire in the church, a 13th-century mural painting in the western semi-dome had to be detached and it was necessary to transfer it to an artificial substrate, in order to save it. A French-Dutch team, under the direction of professor Paul van Moorsel of Leiden University, took charge of this rescue campaign. During this operation an older, underlying painting was exposed. This discovery was the trigger for further investigations. Since 1995, when work in the church was resumed under the supervision of doctor Karel Innemée (Leiden University and currently the Department of Archaeology of Egypt and Nubia, Faculty of Archaeology, University of Warsaw), four different layers of decoration, dating from between the 7th and the 13th centuries, have been identified. In the 18th century these paintings were covered by plaster during a renovation of the interior. Not only these paintings, but also numerous inscriptions found on the walls and architectural details of the church are of great historical and art-historical importance for our knowledge of Christian culture in Egypt and Syria. A number of paintings, especially between the 9th and 13th centuries, were commissioned by Syrian monks, and the large number of inscriptions on the walls, sometimes associated with these paintings, are a treasure trove of information concerning the relations between Wadi al-Natrun and the region of Mosul and Tikrit, the region of origin of many of the Syrian monks at that time (now in modern Iraq, but part of the Syrian region in the 7th –16th centuries). In fact, the paintings from the church are the oldest surviving paintings by Syro-Palestine workshops; the oldest surviving examples from the territories of modern Syria and Lebanon are dated no earlier than the 11th century.

© Deir al-Surian Conservation Project

The long history of the building and its renovations has left the church with a complicated stratification of plaster and mural paintings. So far it has taught us much about how the church must have looked through the consecutive stages of its existence. In the second half of the 7th century, soon after the building was completed, the first preliminary decoration was applied to its interior walls. It mostly consisted of decorative patterns and crosses in cheap pigments: red and yellow ochre. Soon, however, parts of these paintings were whitewashed, and a more monumental series of paintings were executed. At first, a dado-zone was painted throughout the church, a decorative zone of up to two meters high, as an imitation of marble panelling. On the higher parts of the walls and columns, representations of saints were painted, probably over a span of years during the course of the 8th century. At a certain point in the 8th century, the four semi-domes of the church were decorated with a sequence of paintings that show the main events in the life of Christ in which the Virgin is also prominently present. It starts with the Annunciation in the western semi-dome; the adoration of shepherds and magi (Epiphany) is at the northern end of the khurus, while in the now lost apse there was the Ascension. The last scene of the series, most probably Pentecost, is still hidden under a later painting at the southern end of the khurus.

In the 9th century a number of paintings were added to the interior. The most significant of these is a series that commemorates one of the Syriac abbots of the monastery, Maqari. His son and successor Yuhannon commissioned these paintings, which turned the eastern end of the southern side-aisle into a commemorative chapel.

© Deir al-Surian Conservation Project

The 10th century saw the addition of monumental paintings in the khurus and the sanctuary, commissioned by abbot Moses of Nisibis. The two domes in this area were decorated with an elaborate programme of themes from the Old and New Testaments, according to a schedule that must have been designed by the abbot himself. A remarkable aspect of these ‘Syriac’ paintings is that they contain various Coptic inscriptions and were executed in harmony with the earlier Coptic paintings, illustrating the fruitful coexistence of Coptic and Syriac monks in the community.

During the total renovation of the church in the 13th century, all earlier paintings were covered and the interior was fully repainted. Apart from the paintings in the three surviving semi-domes, little is known about the total iconographical programme of this phase, since most of the 13th-century plaster was removed again in the 18th century, when the church was renovated once more.

© Deir al-Surian Conservation Project

Texts

Apart from mural paintings, the removal of the 18th-century plaster has also yielded numerous texts, some written in ink, others painted on the walls as an official part of the paintings or added by visitors. A great variety are preserved, ranging from simple graffiti by visitors to elaborate commemorative texts. So far texts have been found in Coptic, Syriac, Greek, Armenian and Arabic. The special importance of these texts lies in the fact that they help to date the paintings and the layers of plaster on which they were applied, as well as contributing to our knowledge of the history of the monastery, its inhabitants and its visitors. Some of the names of monks that were found on the walls also occur in manuscripts from the monastery’s library, many of which are now in the British Library. Combining information from these sources is an important aid to writing the monastery’s history.

This article can be re-printed with photographs free of charge provided that the source is cited

Bibliography

Website of Deir al-Surian Conservation Project http://deiralsurian.uw.edu.pl

K.C. Innemée, Dayr al-Suryan: 2023 Update of New Discoveries. https://ccdl.claremont.edu/digital/collection/cce/id/2185/

K.C. Innemée, ‘The newly discovered paintings in the dome over the sanctuary in Deir al-Surian’, Byzantinische Zeitschrift 116-1 (2023), 53-76.

K.C. Innemée, ‘The Church of the Holy Virgin in Deir al-Surian – new insights in its architecture’ Bulletin de la Société d’Archéologie Copte 60 (2021) [2024], 151-166.

K.C. Innemée, G. Ochała and L. Van Rompay, ‘Pages of a Chronicle on the Wall: Texts, paintings, and chronology in Deir al-Surian’ in Hugoye, Journal of Syriac Studies 26 (2024), 331-374.

K.C. Innemée, L. Van Rompay and D. Zielińska, ‘The Church of the Virgin in Deir al-Surian (Wadi al-Natrun): Architecture, Art, and History between Coptic and Syriac Christianity’ in E. Bolman, S.F. Johnson and J. Tannous (eds), Worlds of Byzantinium, Cambridge University Press 2024, 280-323.

Author: Karel Innemée

Editor: A.B.

English proofreading by Stephanie Aulsebrook

This text was funded by the project entitled “Promotional campaign for Faculty of Archaeology UW’s research in the Nile Valley”, a part of the Inicjatywa Doskonałości – Uczelnia Badawcza program.