You thought only cavemen lived in caves? What about a 19th-century potter?

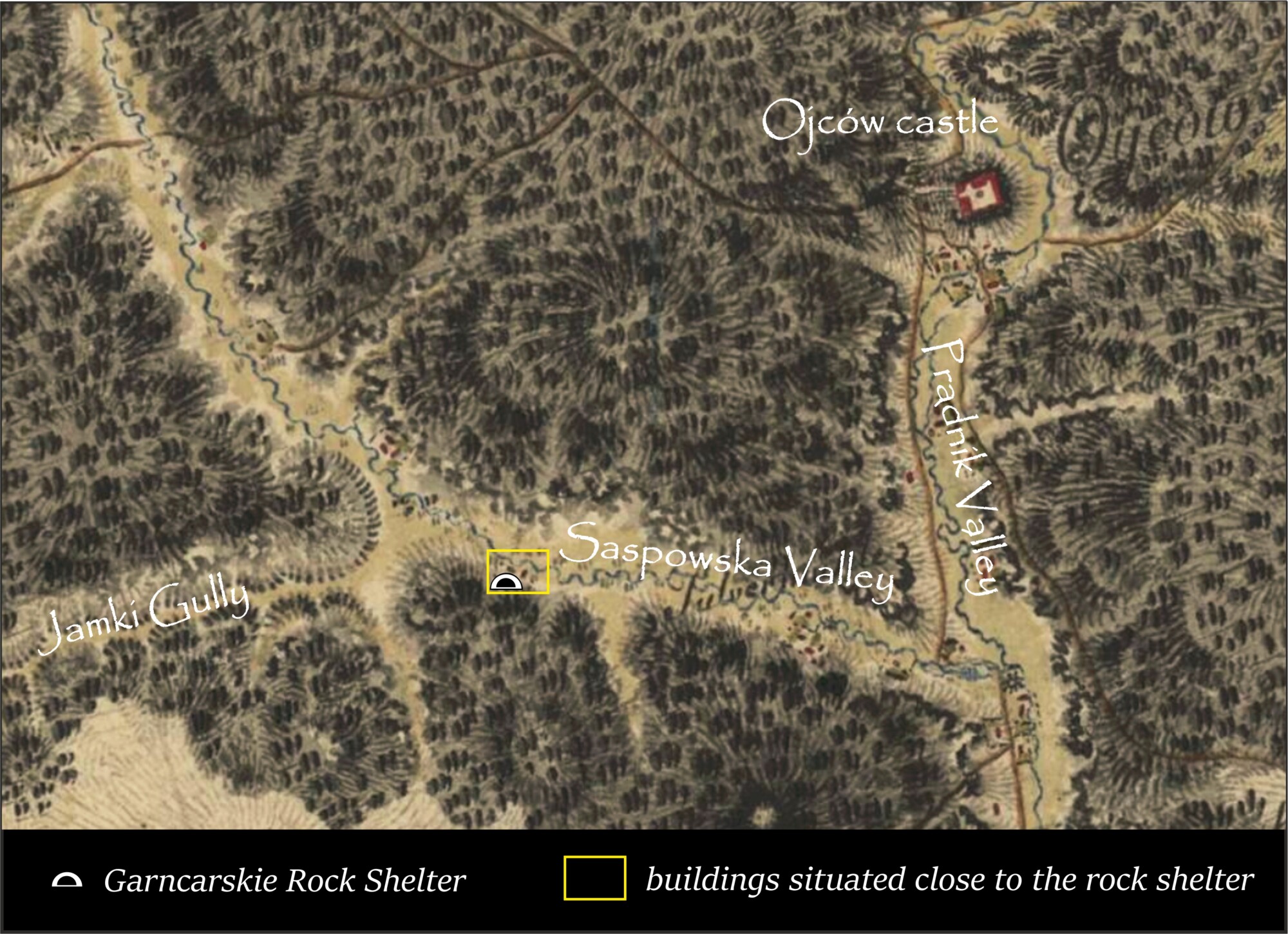

Today, the people who take a walk in the Sąspowska Valley in the heart of Ojców National Park find it difficult to believe that just 100-200 years ago there were more than ten farms scattered on both sides of the Sąspówka stream that wound on the bottom of the valley. One of the households was situated near the outlet of Jamki Gully, directly below vertical rocks that are more than 20 m high. This household is marked on a map of Western Galicia, drawn in 1801-1804 by the Austrian colonel Anton Mayer von Heldensfeld after the annexation of this territory by Austria-Hungary. There were three or four small structures on the right bank of the stream.

The rock is slightly concave in this place and it forms a relatively spacious shelter. On one side there is a slit in the rock that resembles a vertical chimney, which is not insignificant for our story.

Here, on this rock, I shall build my workshop!

Were all the successive inhabitants of this household potters? We don’t know that. But we know that in the 19th century (most likely in the second half) there lived a potter, who organized his workshop in the rock shelter situated at the back of his house. He built a kiln for firing pottery there. He did not do it in a random place, but directly below the natural slit in the rock. The smoke would be released through this slit like through a chimney. The rocks shield the kiln on three sides, shutting off wind. This means the place is sheltered, which is essential for the firing of pottery, since rapid changes in temperature might damage the fired vessels.

©M. Bogacki, na licencji CC BY-NC-SA 4.0

The potter can quietly make and dry his vessels, as well as undertake the long task of firing, lasting 10 to 15 hours. He uses a fast-turning potter’s wheel and before firing he covers the vessels with glaze to reduce liquid penetration and make their appearance attractive. Depending on the chemical composition, the glaze turns greenish, yellowish or brown during the firing. Some vessels break or become deformed during this process. These vessels are thrown away to the earthen floor near the kiln.

How do we know that? Exclusively from archaeological excavations.

Strange discoveries made by Professor Chmielewski

Professor Waldemar Chmielewski shows up at this rockshelter in 1962. He excavates a small trench below one of its walls. He wants to check whether he could find older Pleistocene sediments (from the glacial period) at sites located so low. He does not find any.

However, he comes across a system of pits. One – situated directly next to the wall of the shelter – is filled with ash. The other, apart from charcoals and ash, contains a considerable amount of daub, that is, irregular lumps of clay, as well as many fragments of pottery. He collects them conscientiously, packs in boxes and takes to archaeological storerooms at the University of Warsaw. He never publishes his results.

Storerooms at the University of Warsaw 60 years later

We reach out for these boxes as part of our work in the project of compilation of the Professor’s findings. The vessels discovered then definitely came from the 19th century, which is indicated by the characteristic shaping of their mouths, the composition of the clay body, as well as the yellow and particularly the brown glaze. These types of glaze are very characteristic of the late modern period pottery in Lesser Poland.

We discover isolated fragments of similar modern period pottery almost at each site. Humans have always found caves interesting. It is not different in the modern period, but humans go to caves rather seldom. Sometimes they make a fire there or, less often, set up a temporary camp. In this case, the situation is different. Intrigued, we begin to analyse the work of Professor Chmielewski.

Current research

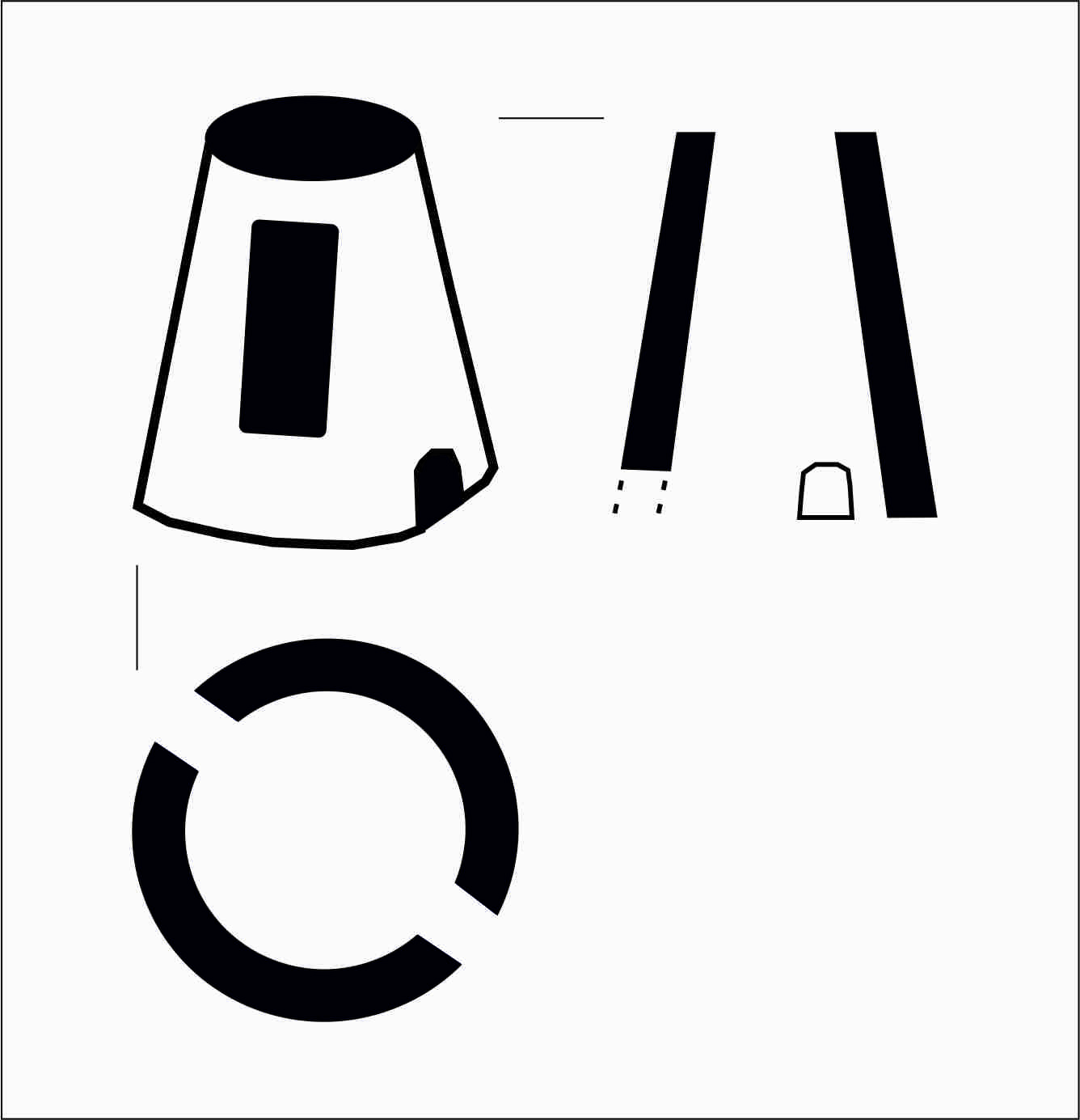

We read the documentation, with the drawings of the walls and maps of the trench. We analyse the pottery. The two communicating chambers are relics of the firing kiln. This is indicated by their shapes and remains of daub. When the kiln ceased to be used, its walls collapsed and filled the chamber with fragments of smashed fired clay, professionally described as daub..

The excavated trench did not contain the whole kiln, but only its fragment. We draw the kiln on the basis of the outlines of the pits and try to reconstruct the part that has not been explored. We only have a partial contour of the kiln at its base. We browse ethnographic literature in search for pottery kilns of parallel shapes, including those resembling our case. Eventually, we find a kiln structure that matches the drawing of the pits.

It’s a simple kiln

The shape of the kiln was a vertical cylinder of a diameter exceeding one metre. The walls of similar pottery kilns built of clay reach 2.5 to 3 m of height and were slightly inclined towards the centre. The wood was loaded during the firing process through two holes situated at the ground level. Most likely there was one more hole at a height of approx. 1 m above the ground, which was used to place the fired vessels in the kiln and then take them out.

Pottery in Jamki Gully

The potter threw simple vessel forms, mainly pots, which were generally used locally. These vessels were not particularly carefully made or intricately decorated. A few specimens were made of white clay, which is interesting due to the fact that we have not found a source of such clay in this area.

We can assume that the kiln did not stand in an open field, and that the potter constructed a wall around the rockshelter and built a type of shed attached to the rocks. So far, we have not discovered direct evidence for that, but we are aware of isolated relics of similar types of structures around caves dating to that period. For instance, a man shielded the entrance and organized a dwelling area inside Krowia Cave, near Cracow Gate in the 18th century. Some small rockshelters are still used as sheds or storerooms. In the village of Sąspów, located near the source of the Sąspówka stream (3 km up the stream), one of the Neolithic archaeological sites is situated in a rockshelter, which today is used as a storeroom.

The time is important

It was not easy at all to establish when the pottery workshop functioned at the site. Similar pottery was made from the late 18th century to the early 20th century. The map drawn by von Heldensfeld tells us that unidentified structures in the proximity of the site already existed at the beginning of the 19th century. However, a map from 1907 does not show these structures. Additionally, one of the first archaeologists to explore this area, Stanisław Czarnowski, paid a visit to this site and found no remains of the pottery kiln or houses located nearby. He only made a note in 1910 that a few old fruit trees grew near the site and the local people remembered that a potter had lived in this area earlier. When we combine this documentation with the results of pottery analysis, we can safely conclude that the pottery workshop functioned at the site in the 19th century, most likely in the second half.

Today there is no trace of the potter’s household and workshop. An astute observer might only discern a strongly cracked and shattered rock. This is where the heat belching from the potter’s kiln moved – it overheated the rock and lead to cracking. There is also the name – Garncarskie (Potter’s) Rock Shelter in Garncarskie Rocks.

This article can be re-printed with photographs free of charge provided that the source is cited

Authors: Małgorzata Kot and Michał Wojenka

Dr Michał Wojenka – an archaeologist dealing with the Middle Ages and the modern period. He is fascinated by Early and Late Medieval defensive structures in the territory of modern Lesser Poland. The issues associated with exploitation of cave sites in the Middle Ages is another subject of his research interest. He works as an Associate Professor at the Department of Medieval and Modern Period Archaeology of the Institute of Archaeology of the Jagiellonian University.

This text was funded by project entitled “From caves to public: A series of popular science articles published on the archeowieści.pl blog, showing a multidisciplinary approach in archaeology, based on the results of our researches in the Ojców Jura” from Inicjatywa Doskonałości – Uczelnia Badawcza programme. Research on the caves of the Sąspowska Valley was funded by the National Science Centre, project: SONATA BIS 2016/22/E/HS3/00486.

References:

Czarnowski S.J. (1907) Dolina Prądnika, Pieskowa Skała, Ojców, Kraków. Ojców: Franciszek Sekuła.

Czarnowski S.J. (1911) Jaskinie okolic Krakowa i Ojcowa i ich zabytki przeddziejowe. Warszawa; Kraków: Wydawnictwo S.J. Czarnowskiego i Sp.

Reinfuss R. (1960) Piece do wypału naczyń w polskim garncarstwie ludowym. „Etnografia Polska” 3, 329-350.

Wojenka M., Kot M. (2019) Ergonomic as a Tool for Fire Structures Reconstruction. Case Study of a Kiln Located in the Garncarskie Rock Shelter in Polish Jura Chain. [in:] Gheorghiu D. (ed.) Architectures of Fire. Processes, Space and Agency in Pyrotechnologies, Oxford: Archaeopress, 81–95.

Project website: https://www.dolinasaspowska.uw.edu.pl