El Castillo de Huarmey, situated approximately 850 kilometers from the Wari heartland on Peru’s Pacific northern coast, emerged as the largest and most important provincial center in the region between AD 800 and 1000. The presence of the Wari culture at El Castillo is undeniable, as it is expressed not only in architecture, but also in funerary practices and by high-quality artifacts. Venerating deceased ancestors was of utmost importance to the Wari. El Castillo de Huarmey itself is a testament to this pivotal element of their past culture. This enormous sepulchral archaeological site covers an area of 45 hectares. A maze of chambers and mausoleums, erected across almost the entire summit of a large rocky spur that extends outward towards the valley, acted not only as an elite necropolis but also as a center of reverence for ancestors. The enormous quantity of ceramics discovered within offering rooms and graves reflects the considerable effort devoted to crafting ceramic vessels for food and beverage consumption, thus fostering a sense of community through feasts that involved both the ancestors and the living.

Who were the Wari?

When we think of empires in the Americas, and ancient Peru in particular, we often immediately think of the Tawantinsuyu or Inca Empire. However, in recent decades, archaeological discoveries have revealed the existence of an even older empire in the Andes: the Wari Empire. Few people have heard of this culture; in fact, almost the only people familiar with the Wari are scholars studying New World archaeology. Nevertheless, this empire was profoundly significant in terms of the development of human civilization in South America. The Wari came to power in the southern highlands of Peru around AD 600. At that time, they represented the most sophisticated and cosmopolitan culture to develop in the Central Andes.

© R. Pimentel, published under CC BY-SA 4.0

The Wari expanded across virtually the entire territory we now call Peru by employing various strategies, from the use of military force to the negotiation of agreements and alliances facilitated by rituals or the exchange of gifts. The empire lasted 300 to 400 years, and then faded away for unknown reasons. During that span of time, the Andean region witnessed significant cultural advancements, including the emergence of complex urban centers and an intricate road network linking administrative centers of various sizes throughout the conquered lands.

El Castillo ceramic collection

Between 2010 and 2023, Polish and Peruvian archaeologists discovered thousands of ceramic fragments at El Castillo de Huarmey, featuring a variety of forms and elaborate decoration. Despite being predominantly made of local clay, a significant portion of the ceramic collection shows a fusion of pottery techniques and iconographic influences from different regions, resulting in hybrid creations combining elements of local, regional, and Wari ceramic traditions.

© R. Pimentel, published under CC BY-SA 4.0

One prominent ceramic group found at Castillo de Huarmey is characterized by the use of molds (generally made of fired clay) with designs on their inner surface into which damp clay was carefully pressed. This technology, rooted in a local pottery tradition, allowed skilled potters to create uniform and standardized forms.

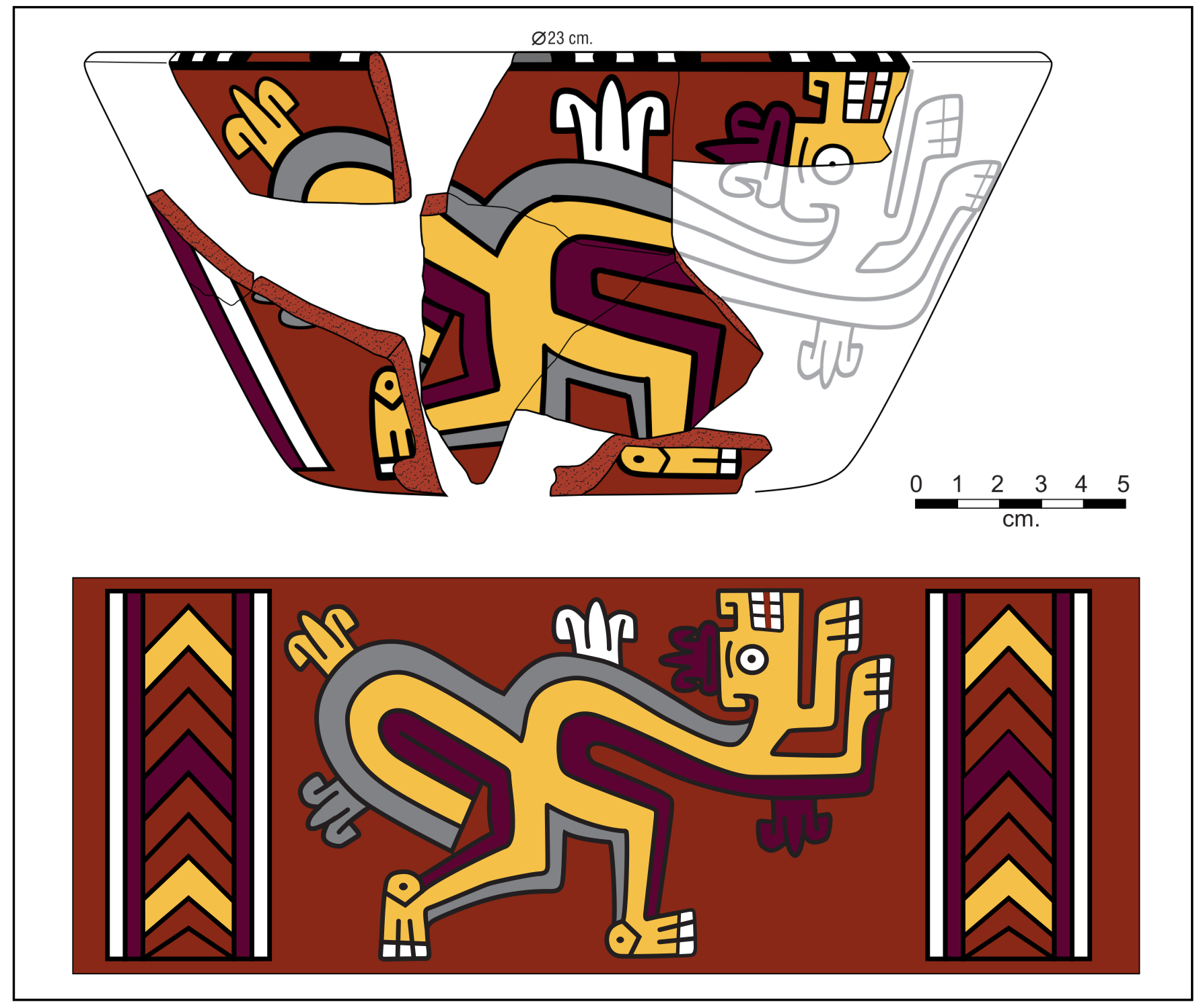

Reconstruction (above) and roll-out drawing (below) based on ceramic fragments.

© R. Pimentel, published under CC BY-SA 4.0

Another significant group comprises polychrome ceramics, showcasing the artisans’ expertise in color and designs. These ceramics are characterized by the application of colorful slips (paint-like substances that are comprised of clay) and intricate iconography, which not only reflects the Wari art motifs but also potential local adaptations or emulations. Among the various figures in this group, one is distinguished as the most significant supernatural being in Wari art, frequently shown wearing very elaborate garments, with appendages radiating around its head and holding staffs.

© M. Giersz, published under CC BY-SA 4.0

Feasting vessels

Feasting vessels were crafted with a spectrum of qualities, indicating distinctions in status among their possessors. Even though the differences might be subtle, each piece was meticulously crafted with great skill and dedication. The most opulent vessels likely belonged to Wari nobles, while simpler versions were probably utilized by local leaders of smaller communities. Wari feasting activity at El Castillo de Huarmey is manifested through the remains of festive meals consisting of camelids, seashells, fish, and a wide variety of plants, as well as various concentrations of decorated vessels in a multitude of forms and sizes. Regular and large jars were used as storage vessels for liquids, likely fermented chicha (a native alcoholic beverage made from maize). We are able to pinpoint specific substances and ingredients consumed or stored in vessels thanks to as analysis of remnants of pollen and phytoliths from the inner surface of a few certain jars has revealed.

© M. Giersz, published under CC BY-SA 4.0

The necks of some jars feature human faces with details such as eyebrows depicted by black lines, prominent noses occasionally adorned with nose rings, and ears with large orejeras. Many of these jars received special treatment prior to their placement in the mausoleums, as remains of cinnabar (mercury sulfide) were found on the modeled faces, resembling facial paint. It is likely that these traces indicate the performance of rituals before placing these vessels in the graves; similarly, the faces of individuals interred in the different mausoleums in the site had been painted with a sacred red pigment.

© W. Więckowski, published under CC BY-SA 4.0

Cooking pots are found blackened, likely resulting from contact with the fire or the proximity of fuel during firing. The bottles featuring narrow spouts are also present. They were designed for transferring liquids, which might have been initially crafted with a particular purpose in mind, possibly for a single use or for a specific offering. We can see from the tableware that bowls and cups were the preferred choice for consuming either solids or liquids respectively.

Toasting with the ancestors

The Wari and their wealthy ruling class frequently engaged in ritual consumption of chicha using highly decorated pottery vessels. About a third of the vessels discovered in the most important mausoleum were cups, otherwise a rarity in the archaeological record, hinting at their potential use for special occasions and celebrations. These cups varied in size, ranging from personal-sized to much larger ones. The largest cup discovered at El Castillo de Huarmey could hold nearly three liters of maize beer, which was likely shared among several participants, an ancient echo of a modern Andean drinking tradition.

© R. Pimentel, published under CC BY-SA 4.0

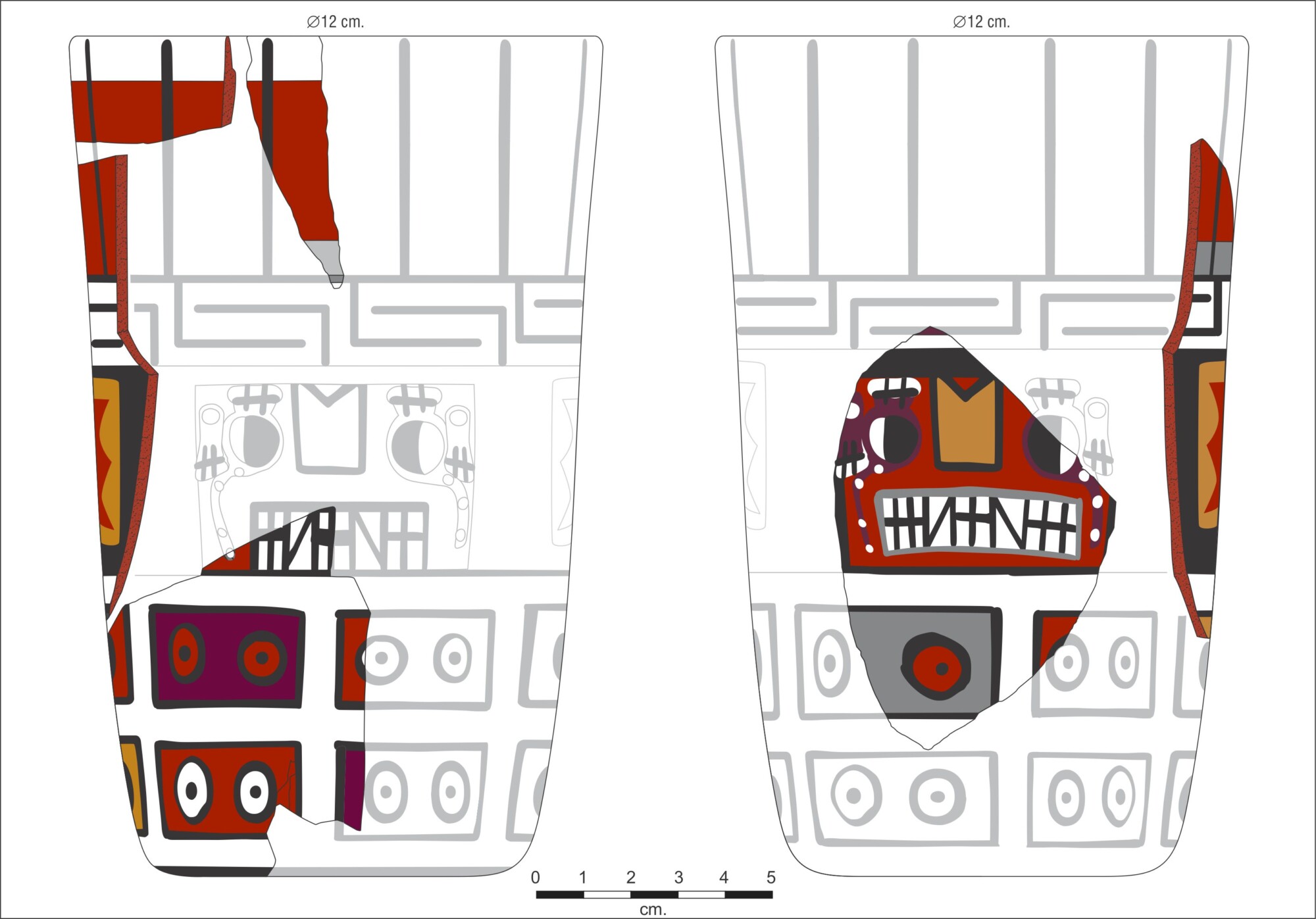

Ceremonial drinking cups unearthed at El Castillo de Huarmey exhibit elaborate decoration, depicting mythical beings or episodes that likely symbolized important actions or legendary events. Similar to the Inca keros, certain Wari cups discovered at El Castillo de Huarmey were crafted as matched pairs, possibly used for symbolic toasts with ancestors. Chicha would be offered in one cup to be “consumed” by the thirsty ancestors by pouring it onto the ground, while the officiant would drink from a matching cup. In return, the ancestors, as the life force residing in the underworld, reciprocated with water and crop fertility.

Reconstruction and drawing based on ceramic fragments

© R. Pimentel, published under CC BY-SA 4.0

From ancient times to the present, both this belief and practice persist in traditional Andean societies, where the custom of celebrating in cemeteries with deceased ancestors during annual festivities has been maintained. Beverages, food, and vessels play fundamental roles in these celebrations, where the realms of the living and the dead intertwine.

This article can be reprinted free of charge, with photos, and with the source indicated

Roberto Pimentel Nita – Peruvian archaeologist and PhD candidate in Archaeology at the Doctoral School of Humanities, University of Warsaw in Poland. His research focuses on Wari ceramic production at El Castillo de Huarmey. For eighteen consecutive years, he has been a member of two Polish-Peruvian archaeological projects on the northern coast of Peru: Valle de Culebras and El Castillo de Huarmey. Since 2010, he has co-directed excavations at El Castillo, participating in the discovery of the first intact mausoleum of the highest Wari elites. He has been awarded the Bene Merito honorary distinction by the Republic of Poland (2015) in recognition of his efforts in promoting Poland abroad.

Editor: A.B.

Proofreading: S.A.

Cover: The painted figure on this ceramic bowl depicts a feline-like creature with human-like hands and feet, an image often seen in Wari art

Reconstruction (above) and roll-out drawing (below) based on ceramic © R. Pimentel, published under CC BY-SA 4.0, ed. K.K.

This text was funded by IDUB and the project entitled “Popularizing the research of the Department of Archaeology of the Americas at the Faculty of Archaeology” from Inicjatywa Doskonałości – Uczelnia Badawcza programme.