Despite substantial evidence on the short-term effects of adverse climate shocks, our understanding of their long-term impact is limited. To address such a key issue, research has focused on ancient societies because of their limited economic complexity and their unparalleled experience of environmental and institutional change. Notably, ‘Collapse Archaeology’ literature has reported statistical evidence consistent with the mantra that severe droughts trigger institutional crises. This view, however, has recently been challenged by literature summarized in the paper Climate Change and State Evolution by Giacomo Benati and Carmine Guerriero.

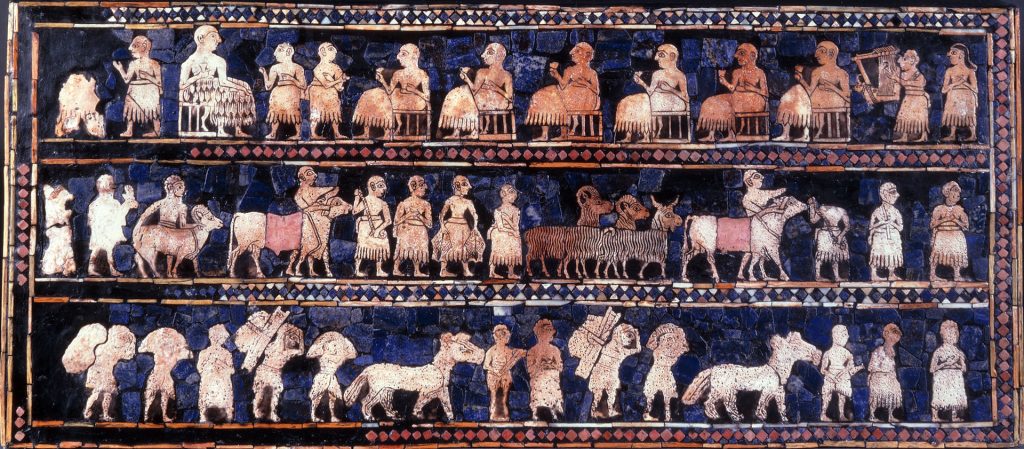

© G. Benati

Climate change and the elites

Using more detailed data on 44 major Bronze Age Mesopotamian polities and an empirical strategy designed by making use of state-of-the-art econometric theories of state formation, yields two novel results. First, severe droughts encouraged the elites to grant strong political and property rights to the non-elites in order to woo the latter. A sufficient proportion of the returns from joint investments would be shared via public good provision, thereby fostering a culture of cooperation. Second, a more favorable climate allowed the elites to elicit cooperation under less inclusive political regimes, a weaker culture of cooperation and, possibly, incomplete property rights for the farmers.

Climate change in state evolution

This second empirical result is consistent with the evolution of the earliest recorded forms of state institutions in Bronze Age Mesopotamia. The increasingly cold and dry climate at the end of the Urban Revolution period (3800-3300 BCE) threatened consumption and thereby enhanced the importance of irrigation infrastructures. The consequent need for labor-organization promoted a shift of decision-making power from the landholding groups to the temples. Exploiting this new role, religious leaders obtained, over the Late Uruk period (3300-3100 BCE), command over public good provision and proposed a culture of cooperation in the provision of consumption risk-sharing activities: storing agricultural output, supplying grain in times of famine, regulating interest rates, and organizing craft activities.

Further evidence is provided by the droughts at the onset of the Early Dynastic period (3100-2550 BCE), when declining agricultural yields encouraged the temples to share their power with emerging palatial elites. These elites exchanged tenure-for-service agreements for employment in public building projects and conscription. Conscripted workers gained political power and benefitted from alternative means of consumption risk-sharing: victuals, garments, access to irrigation, and draft animal power in peacetime, in addition to military spoils. The formation of a conscripted army became the preferred public good for the non-elites.

Third, the more favorable climate of the pre-Sargonic period (2550-2350 BCE) curbed the elites’ need to entice the non-elites, expediating the evolution of royal dynasties into supreme executive bodies. Also, the harsher climate of both the Akkadian and Old Babylonian periods (2350-1750 BCE), facilitated the emergence of long-distance exchange as an alternative to farming, and prompted the elites to begin sharing their power with the merchant guilds to produce trade-related public goods. Finally, over the entire Bronze Age, adverse climate shocks were never so fierce as to impede all cooperation.

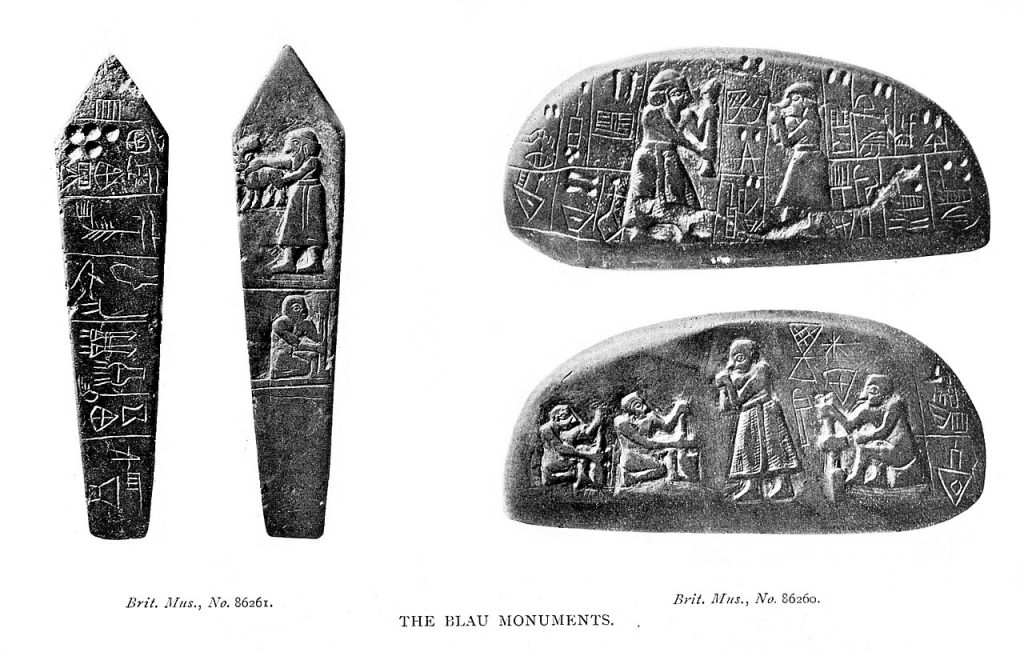

L.W. King, A history of Sumer and Akkad : an account of the early races of Babylonia from prehistoric times to the foundation of the Babylonian monarchy, 1910, Public Domain

Policy implications

Two principal policy implications emerge from our research. First, severe droughts depress the economy in the short term, but over the medium to long term they foster cooperation between the elites and non-elites which would otherwise have been unachievable. Cooperation is facilitated by encouraging the participation of elites and non-elites in joint investments, which strengthens property rights. Analysis, based on ancient history, provides a framework which can be used to assess the success of current responses to the Covid pandemic.

Second, provided the political-economic environment generates a sufficiently large output for the population to share, less inclusive political regimes can nonetheless incentivize joint investments, especially if the non-elite appreciate the benefits of cooperation.

Conclusions

To conclude: our findings support the proper combination of natural and social sciences when evaluating the total effect of major climate shocks. Such an approach requires detailed and historically rigorous data on regional climate change, institutions, economic outcomes, and convincing theoretical models if we are to increase the credibility of empirical tests.

More detail can be found in the paper Climate Change and State Evolution by Giacomo Benati and Carmine Guerrio.

This study stems from projects conducted at the University of Bologna and funded through both the AlmaIdea 2017 and the Montalcini 2015 programs. We are grateful for the participation of Federico Zaina (Polytechnic University of Milan) and Laura Righi (FSCIRE) in these projects.

This article may be freely reprinted without photographs, with reference to the source

Authors:

Giacomo Benati is a postdoctoral fellow at the Faculty of Economics and Social Sciences, Eberhard Karls University Tübingen. His research targets the origins and development of political institutions in the ancient world through an interdisciplinary approach combining history, archaeology, and quantitative methods. He has taken part in archaeological fieldwork and cultural heritage enhancement initiatives in Italy, Turkey, and Iraq and has published in top journals in the field of archaeology, Mesopotamian studies, and institutional economics.

Carmine Guerriero is “Rita Levi-Montalcini” Associate Professor of Economics at the University of Bologna and Editor-in-Chief of the Cambridge-based Elements in Law, Economics and Politics. His chair has been established thanks to a 3.4 million euro 2016 Rita Levi-Montalcini grant from MUR. His main contributions concern the understanding of the determinants and impact of regulatory, legal, and political institutions and have been published in top economics, law, political science, and multidisciplinary journals.

Editor: J.M.C

Proofreading: Stephanie Aulsebrook