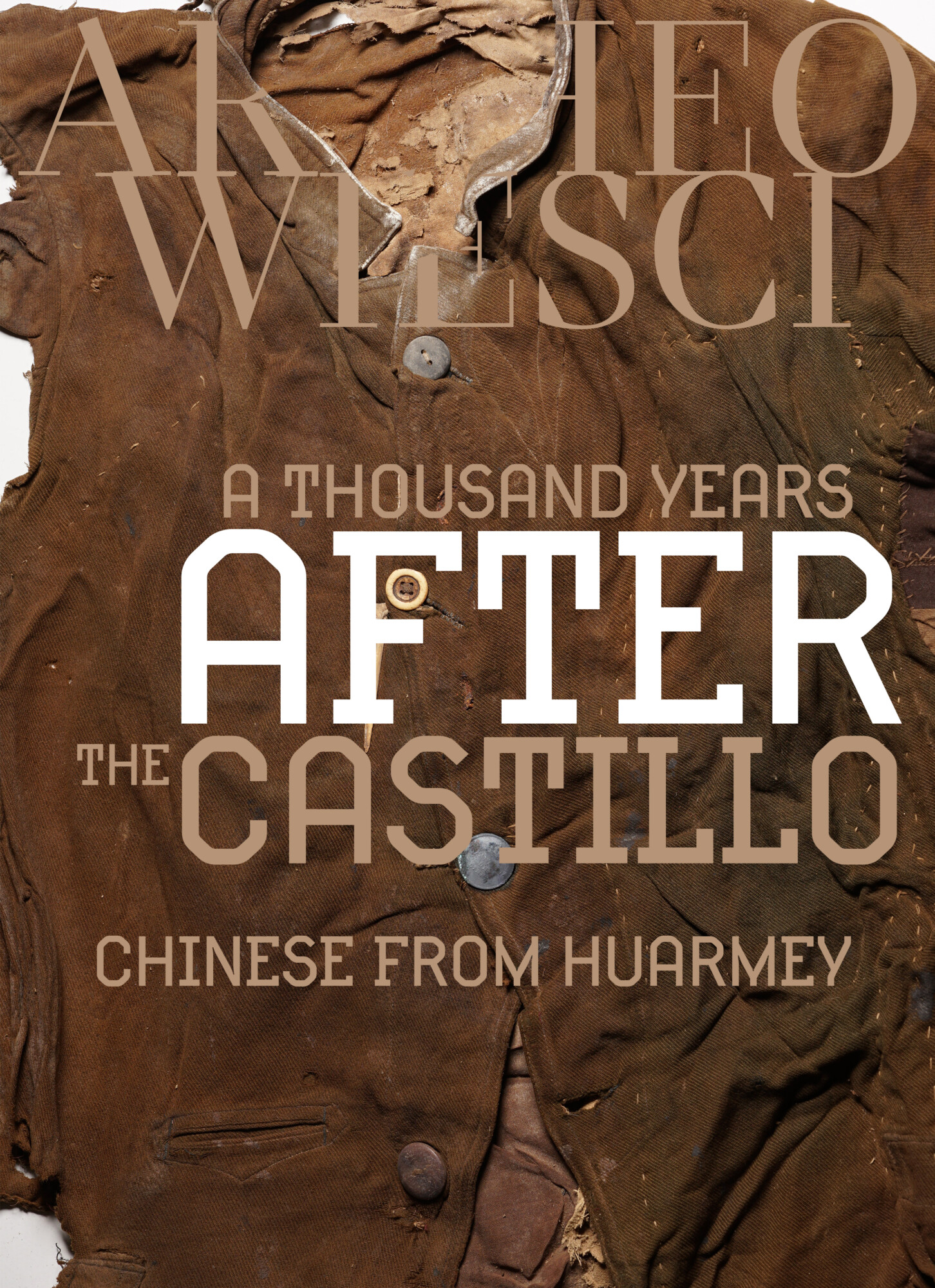

One of the most unexpected and surprising discoveries at Castillo de Huarmey site were the burials dated to the very beginning of the 20th century. They were found within palacio, which is the architectural establishment located at the foot of the hill on which the mausoleum is situated, from which the Castillo de Huarmey is best known. The whole area of this archaeological site functioned as a burial site at least since the Early Horizon (see: Tysiąc lat przed Castillo: Atypowe pochówki z Huarmey ENG!) through the Middle Horizon (these burials were associated with the presence of the Wari Empire in the area), to the Late Horizon. However, discovery of the much younger burials indicate that Castillo functioned as the funeral zone in the minds of even 20th-century residents of the Huarmey Valley. Certainly the hill and overlooking mausoleum, were strongly distinguished in the local landscape (before the great earthquake of 1970 probably it might dominate evenmore so than today), was considered as huaca, which means a “sacred place.” Similar to the platforms of the Moche Valley, or those in the area of modern Lima (e.g. Huaca Pucllana located in Miraflores district).

DISCLAIMER: THIS ARTICLE CONTAINS PHOTOS OF HUMAN REMAINS

Continue reading “Thousand years after Castillo: Chinese immigrants in Huarmey”