The recent volume of Bioarchaeology of the Near East contains three regular papers and eight short fieldwork reports, with a broad range of topics. Nina Maaranen and colleagues from the ERC Hyksos Enigma project present research on dental non-metric traits at Avaris, the Hyksos capital city, compared to other samples from Egypt. Their results indicate that the people of Avaris were of different ancestry than Egyptians, supporting the hypothesis that a large-scale migration from the Levant to the eastern Nile delta occurred during the Second Intermediate Period.

Berdysyčran-depe – a new site of the Oxus civilisation in the Tedjen alluvial fan

© B. Kaim

Berdysyčran-depe, a hitherto wholly unknown and inconspicuous site located in Turkmenistan in the ancient Tedjen River (Hari Rud) alluvial fan, turned out to have hidden remains of the Oxus civilisation.

Just two days after the publication of the results, the news about the discovery by Polish archaeologists was described by the N+1 portal. Soon it was quoted across various services popularising science and internet forums. That prompted us to write about this discovery on the Archeowieści portal.

Continue reading “Berdysyčran-depe – a new site of the Oxus civilisation in the Tedjen alluvial fan”

How long did women in the ancient Near East breastfeed?

The length of the period of breastfeeding depends on many factors, both individual and cultural or environmental ones. In human societies that have no access to easily digested food alternatives (this refers to foragers in particular) this period is usually longer, while in farming communities, where infants are fed with porridge or yoghurt, it can be shortened. This implies demographic consequences: a mother who breastfeeds her child for a shorter time can have more children, therefore, the breastfeeding period influences the birth rate.

© Osama Shukir Muhammed Amin FRCP(Glasg)

published under CC BY-SA 4.0, via Wikimedia Commons

Continue reading “How long did women in the ancient Near East breastfeed?”

Bi(bli)oArch: Bibliographic database for human bioarchaeological studies in the Eastern Mediterranean and Middle East

Scholars from the Cyprus Institute, Nicosia, have prepared a bibliographic database for human bioarchaeological studies in the Eastern Mediterranean and Middle East (EMME), chronologically covering skeletal assemblages from prehistory to early modern times.

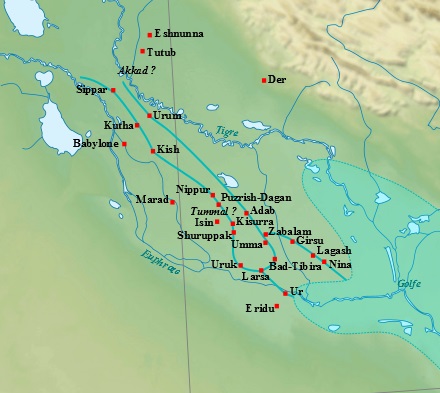

1739 BC – year when the Sumerian civilization collapsed

Sumerians are known as the founders of the urban civilization that dominated in southern Mesopotamia in the 4th and 3rd millennia BC. They developed a network of irrigation channels that made it possible to cultivate cereals in desert areas of the Lower Euphrates, introduced an ideographic script, initially pictographic and then simplified to the form of cuneiform characters impressed in wet clay, built the biggest cities in the world at that time, with monumental temples and enormous palaces.

Near_East_topographic_map-blank.svg: Sémhur(published under CC BY-SA 3.0, via Wikimedia Commons)

Continue reading “1739 BC – year when the Sumerian civilization collapsed”

Rapid change of climate did not cause the fall of the Akkadian Empire

The latest issue of Antiquity published a paper presenting results of biochemical analyses of human bones from a few sites situated in north-eastern Syria, and showing on this basis that in the 22nd century BC, when the Akkadian Empire was declining, there was no change in the local economy which could be a response to a long-term drought, and even if there was a temporary climate change, the local human societies survived it in a good condition.

© F. Romero, France – Paris – Musée du Louvre, published under CC BY 2.0, via Wikimedia Commons

Continue reading “Rapid change of climate did not cause the fall of the Akkadian Empire”

Climate change and state evolution

Despite substantial evidence on the short-term effects of adverse climate shocks, our understanding of their long-term impact is limited. To address such a key issue, research has focused on ancient societies because of their limited economic complexity and their unparalleled experience of environmental and institutional change. Notably, ‘Collapse Archaeology’ literature has reported statistical evidence consistent with the mantra that severe droughts trigger institutional crises. This view, however, has recently been challenged by literature summarized in the paper Climate Change and State Evolution by Giacomo Benati and Carmine Guerriero.

© G. Benati

[INTERVIEW] Rolling in the deep – emerald mines in the desert

Some time ago we wrote about the ancient port of Berenike on the Red Sea coast. This time we had an opportunity to talk with dr Joan Oller Guzmán from Universitat Autònoma de Barcelona, who in 2020 and 2021 conducted an archaeological survey in the Mons Smaragdus region of the Egyptian Eastern Desert. This region was known in Antiquity as the only source of emeralds within the borders of the Roman Empire!

We invite you venture further into this article, where dr. Guzmán tells us about exploring underground galleries and what they have found in the dungeons deep.

© J. O. Guzman

Continue reading “[INTERVIEW] Rolling in the deep – emerald mines in the desert”

Animal dung as a strategic resource in the kingdom of Mari

Kings of Mari controlled an important trade route in the valley of the Euphrates River in the 3rd and early 2nd millennium BCE. Although their country was situated in an area with unfavourable conditions for agriculture, the economy of the kingdom of Mari could support a big population. The key to understanding this paradox is animal dung.

The kingdom of Mari was the most powerful country of north Mesopotamia in the 3rd and early 2nd millennium BC. Its power is reflected both by the size of its capital (modern archaeological site of Tell Hariri), which occupied an area of more than 60 hectares – more than Cracow in the 13th century – and by the fact that six of its rulers were included in the Sumerian King List, that is a record of the dynasties that were regarded as those holding superior power in Sumer. The dynasty from Mari was the only dynasty from north Mesopotamia on this list.

Photo: Herbert Frank

(Published under CC BY 2.0, via Wikimedia Commons)

Continue reading “Animal dung as a strategic resource in the kingdom of Mari”

Conference “Poles in the Near East”

The fifth edition of the “Poles in the Near East” conference begins tomorrow. During the meeting, over 50 researchers will talk about the results of archaeological and conservation work in the area from the eastern Mediterranean, including Cyprus, through the Levant, Asia Minor, Mesopotamia, Iran, the Arabian Peninsula, to the Caucasus and Central Asia.