“It was a paper envelope with bones inside” – remembers one professor when we ask him about child bones from Bramka Rockshelter. “It was somewhere among documents in professor Chmielewski’s office”. The office was closed after his death. I hold the documentation in hands, but the envelope is missing. This is how the story began.

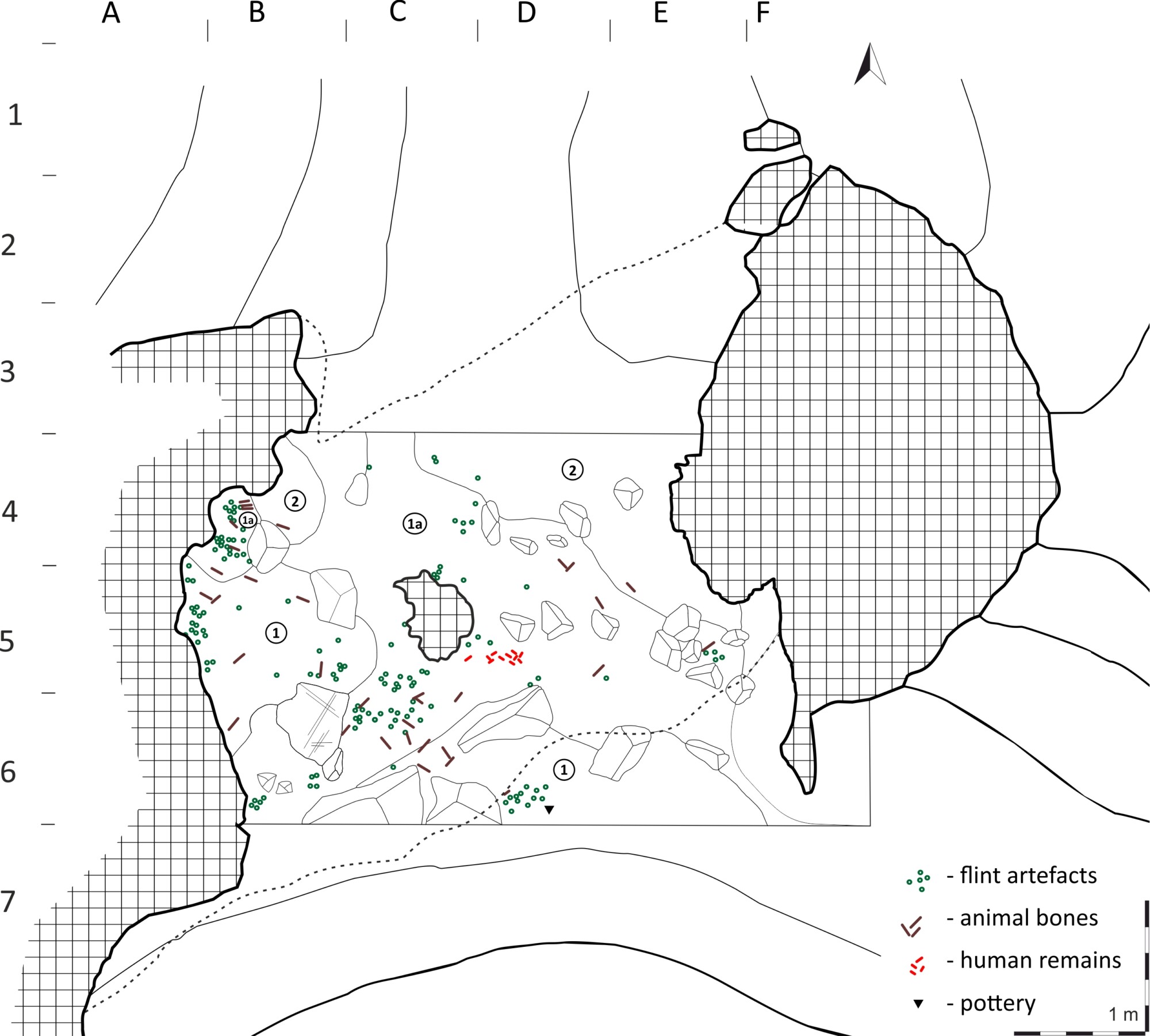

It is 1973. Professor Chmielewski finds a small concentration of light human bones in the trench in the centre of Bramka Rockshelter, which I wrote about in one of the older texts. The anthropologist professor Karol Piasecki established after preliminary examination that the bones belonged to a child that was between 0 and 6 years old at the time of death. The remains were found in a layer which contained Mesolithic artefacts. Consequently, professor Chmielewski assumed that it was a burial from this period. Not a trifle! That would be the first burial associated with Mesolithic hunters from 8700 years ago discovered in a cave. Isolated finds of this kind are known from the territory of modern Germany and Italy.

This is where things get complicated. The bones were placed in a paper envelope and then they were probably left among other cave materials studied by professor Chmielewski for several decades. Neither the burial, nor the whole Mesolithic material from the rockshelter was published. Nevertheless, the professor mentions in a book of geological and palaeontological analyses of the materials from Sąspowska Valley caves that he came across a Mesolithic child burial in Bramka Rockshelter. This means the discovery was known in scientific circles in 1988, but only from a brief note. After the professor’s death the office was closed, and the documentation, together with books and many documents, was transported to the new location of the Institute of Archaeology.

© M. Kot on the basis of field documentation from 1970 and 1973 excavations, CC BY-NC-SA 4.0 licence

In 2017 we launched the project of analysis of materials collected by the professor and began from a search for all the artefacts and field documentation. Bramka Rockshelter was a site for which both some of the documentation and some materials were missing from the start. We asked about them and looked in all boxes again. Eventually, we managed to find almost complete documentation of the studies of the site. We only failed to find the site record and the paper envelope with the child bones. Those employees who still remembered the professor’s office described the envelope and its contents in detail. We even found the preliminary analysis of the bones conducted by professor Piasecki. However, the bones were still missing.

Equipped with this information, I began research at the site in Bramka Rockshelter in 2017. After talks to the geologist, professor Madeyska, who worked with professor Chmielewski, we decided that it would be most reasonable to start with floatation of the heap of soil excavated during the previous studies. The work turned out to be more difficult than we thought since the rockshelter is situated about 50 m above the bottom of the valley, on a steep slope. It seemed total madness to carry several hundred bags of soil down the slope. Fortunately, the students from the University of Kharkiv who worked with us at that time thought that the bags could be moved down along ropes tied high onto trees. As the valley slopes are covered by a thick beech forest, we needed to use three independent zip line systems. Each bag was packed into a bucket near the Rockshelter. Then it slid down the rope and was re-packed twice into buckets tied between other trees, finally landing on the bottom of the Sąspowska Valley. Then the soil was subjected to standard flotation procedure on sieves, drying and next we used tweezers to collect any objects of interest. In this way, we found 6000 Mesolithic artefacts and many small, fragmented, partially burned bones.

All the bones were then sent to a bioarchaeologist from our Faculty, Dr Elżbieta Jaskulska, who examined them and collected human bones. This assemblage contained a bone of a child who was 2 years old at the time of death at most. It was the shaft of one of the metatarsal bones. I was speechless when I saw the report of anthropological analysis. I hurried to look for the old report of the bone analysis of the burial conducted by professor Piasecki. The age of the individual was relevant. Did we then find a bone from the lost child burial? Even if not, it was a bone of a child from that site. We did not wait long to find out: we compiled a 3D-model of the bone and sent it to Oxford for radiocarbon dating. The results arrived a few months later. The chronology of the bone was not established at 9700 years as we expected due to the Mesolithic artefacts from the site, but at 2700 years.

© M. Bogacki, CC BY-NC-SA 4.0 licence

I pondered over the report, wondering how it was possible: 2700 years. This a time when the modern territory of Poland was occupied by societies associated with the Lusatian culture, Late Bronze Age and Early Iron Age. We unearthed almost no artefacts of the Lusatian culture at the site. Caves contain quite a lot of Lusatian artefacts, but we are not aware of any that would contain human remains. We have no evidence for exploitation of caves for funerary purposes by the Lusatian culture. Most interestingly, the Lusatian culture societies initially buried their dead in graves. However, they also cremated the deceased and placed the burned remains in urns, quite often covered with bowls, sometimes equipped with a few more vessels. The burial from Bramka Rockshelter falls to the late phase of this culture, when unburned human bodies were buried extremely rarely. This raises a question: how come there was a burial of a young child up to 2 years old without any marks of cremation? Should it be associated with the Lusatian culture settlement situated nearby, at the Ojców Castle? Why was the child buried in a rockshelter? While no Lusatian cemetery that would correspond with the settlement at the castle has ever been discovered, exploitation of caves for such purposes is not a known routine of that period of prehistory. Our team searched through thousands of publications and we did not find any comparable case!

All these questions remained unanswered until we received results of other radio-carbon analyses of human bones from other caves located in the Sąspowska Valley. Our project involved analysis of all human remains that we would find. We wanted to establish their chronology and check whether the caves were used as burial ground throughout the prehistory, or only in selected periods. A year after we got the results of radio-carbon dating of the child bone from Bramka Rockshelter we also received results for two calcanei unearthed in Zbójecka Cave by Ferdinand von Roemer in the 19th century. These dates again indicated the Lusatian culture, but this time they belonged to two adult individuals. And again, there were no cremation marks. The remains were buried in the cave unburned.

© M. Jakubczak, CC BY-NC-SA 4.0 licence

It all was getting really interesting since Roemer, like other earlier researchers of Zbójecka Cave, reported that many human remains were discovered inside. Unfortunately, the two calcanei are the only items that have survived to our times, and they remained unnoticed among the numerous collection of bear bones that Roemer gathered. They were re-discovered by professor Adrian Marciszak in the course of inventory control at the University of Wrocław and were made known more widely thanks to our chronology analysis.

Public domain

Right now we suppose that this is an earlier unknown and not researched phenomenon of exploitation of caves for funerary purposes by societies of the Lusatian culture. Nevertheless, many questions remain unanswered. Why cremation, so characteristic of this period, was not carried out in the case of these bones? Do these bones come from regular burials of the local people inhabiting the settlement in Ojców, or perhaps of migrating individuals who buried their dead in the cave because there was no other choice? If so, why weren’t these individuals equipped with grave goods? And eventually: can we expect relics of similar practices in other caves, remains that we failed to notice because of displacement and mixing of artefacts and bones found in the highest layers of cave sediments?

Just one bone of a small child, and so many new research questions. This is the beauty of our work!

This article can be re-printed with photographs free of charge provided that the source is cited

Authors:

Małgorzata Kot

Grzegorz Czajka, MA – archeologist of the Bronze Age and Early Iron Age. His research interests include pottery industry and the phenomenon of cave exploitation in the territory of modern Poland by pre-historic societies. Apart from his work, he is fascinated by numismatics, especially Polish coinage from the rule of the Vasa dynasty. He is currently working on his doctoral dissertation and studying at the Doctoral School of Humanities of the University of Warsaw.

This text was funded by the project entitled “From caves to public: A series of popular science articles published on the archeowieści.pl blog, showing a multidisciplinary approach in archaeology, based on the results of our researches in the Ojców Jura” from Inicjatywa Doskonałości – Uczelnia Badawcza programme. Research on the caves of the Sąspowska Valley was funded by the National Science Centre, project: SONATA BIS 2016/22/E/HS3/00486.

References:

Chmielewski W. (ed.) (1988) Jaskinie Doliny Sąspowskiej. Tło przyrodnicze osadnictwa pradziejowego. Warszawa, Prace Instytutu Archeologii UW.

Kot M., Czajka G., Jaskulska E., Szeliga M., Kontny B., Marciszak A., Mazur M., Wojenka M. (2021) Exceptional sepulchral use of caves in Lusatian culture: new evidence from the Sąspówka Valley in the Polish Jura, „Archeologicke Rozhledy” 73, 200–227, doi: 10.35686/AR.2021.7

Olszyński M. (1871) Wycieczka do grot Ojcowskich, „Kłosy” 13, 381–382.

Römer F. (1883) Die Knochenhöhlen von Ojcow in Polen, „Palaeontographica” 29, 193–233.

Römer F. (1884) The Bone Caves of Ojców (Poland). London: Spottiswoode and Co.

Project website: https://www.dolinasaspowska.uw.edu.pl