Although the archaeological site of the Castillo de Huarmey is mainly known for discoveries connected with the presence of the Wari culture in this region (mausoleums and burials associated with elites of this pre-Inca empire), both earlier and more recent features can be found within its area. A cemetery which could be even a thousand years older than the famous Mausoleum was unearthed in the close proximity to the site.

DISCLAIMER: This article contains the photographs of human remains

A small platform of an irregular, slightly oval shape, situated among farmlands somewhat northwest of the main area of the site, is one of such places. Due to its appearance – there is no vegetation on its beige-brown surface, which is clearly visible against the green colour of the surrounding fields – it was called pankeke (pancake). The platform was built by humans and humans (quite recently) tried to destroy it. One of the farmers from its vicinity wanted to expand the area of his field and he breached an edge of the structure, revealing walls constructed of crushed stone. This raised interest among the members of the archaeological team exploring the Castillo, which led to two seasons of excavations of the platform. Results of these excavations were really surprising.

© M.Giersz, licensed under CC BY 4.0

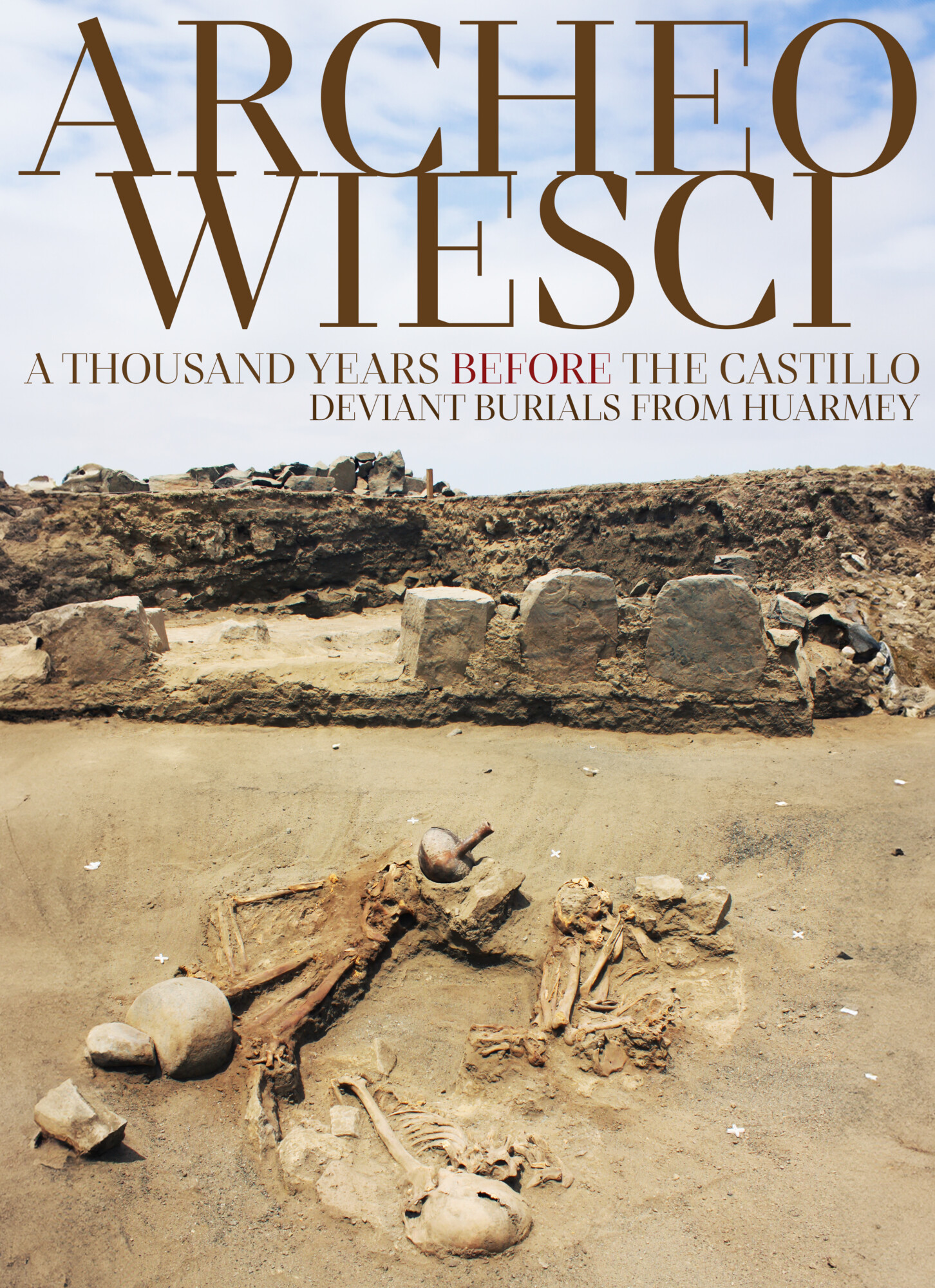

It turned out that the area was exploited already in the Early Horizon (that is, between 800 and 200 BC). Most likely the local people established their cemetery there. Altogether 19 graves were discovered, with 22 people buried in them. The burials were not typical ones. Most of all, there were rather few items of grave goods – just a few very simple beads and fragments of pottery. Only two burials seemed different from the rest in this regard. One contained a very primitive anthropomorphic pottery figurine. Another one was a group burial – a very young child was buried at the lowest level, and then, slightly above, a woman and two men. The older man must have been someone important since he was equipped with a stirrup spout vessel (typical ceramic style of the Early Horizon), a stone mortar with pestle and a vessel made of a sea mussel shell with red pigment in it.

© M.Giersz, licensed under CC BY 4.0

Most of the dead were buried in single graves. Their bodies were deposited in shallow pits dug in the sand. Remains of six adults and three juvenile people were buried in very contorted positions, usually lying on the side and covered with a layer of clay mixed with stones. Remains of children were deposited in various positions, which made it appear as if their bodies were just thrown into shallow pits and covered with soil. This type of burial was quite typical in the Early Horizon and is well-known from many sites in northern Peru.

Four graves attracted the attention of the archaeologists. These features were different from the rest because of the treatment of the dead buried there, and the treatment took various forms.

One of the graves, unearthed back in 2010, accommodated remains of an adult man, whose body was aligned in a peculiar manner during the burial. Normally, a body laid on the side should come with strongly bent arms and legs, drawn towards the trunk, just like in other graves. In this case, however, the body rested on the side, while the strongly straightened legs held with his arms were aligned so that the feet were positioned close to his face. As a result, the dead seems to be performing an acrobatic feat.

© R.Pimentel Nita, licensed under CC BY 4.0

Remains of a child aged about 7 years were found in another of the atypical graves, again buried in a curious manner. Namely, in order to put the body in the ground, a relatively deep but very narrow pit was dug, then a big shell of a sea mussel (Concholepas concholepas) was placed on the bottom together with big fragments of both pelvic bones of a woman on its sides. In addition to that, a fragment of a scapula of an adult person was placed under the shell. Then the body of the child was “pushed” into the pit so that the head should rest on the shell and between the pelvic bones. The arms and legs were aligned to rest strongly bent and drawn to the trunk. Why should so much effort be exerted to arrange the grave of this particular child while other ones were just randomly “thrown” into the pits, even with their faces down?

© R.Pimentel Nita, under licence CC BY 4.0

Another grave contained remains of a younger adolescent. Again, the body was positioned in a strange manner. Above all, it seems the corpse was cut in two and only its upper part was placed in the grave. This part was positioned face down and the alignment of the hands and arms suggests they were tied up behind the child’s back. Why was it so? Who was the child? It is extremely interesting that the child suffered from several diseases and a number of pathologies. Firstly, the skull shows very advanced changes called cribra orbitalia. They are often associated with acute anaemia (caused by various factors – genetic ones or deficiency of iron or vitamins), which might have been manifested during his or her lifetime in form of various “indispositions”, sometimes even a coma. Apart from that, the child’s spine was deformed. One of the lower thoracic vertebrae was characterized by malformation of the lateral part of the vertebral body, which led to severe scoliosis and possibly excessive kyphosis. In other words, the child had a bad posture, uneven shoulders, distorted shape of the trunk and even a growing hump in the middle part of the back. Was the child buried in a such a strange way because of such appearance?

The last “strange” burial accommodated remains of an adult, again positioned in an atypical way. Above all, the skeleton was incomplete – there was no head in the grave, bones of one arm and legs were missing, although the feet bones were complete. The body, or rather its fragments were arranged as follows: the feet were placed next to each other on the bottom of the pit, then a strongly bent trunk (preserved from the neck to the pelvis) with one arm was put atop. Two quite big stones were placed in the expected location of the skull. Why was the body buried fragmented? What happened to the missing parts of the skeleton?

© M.Giersz, under licence CC BY 4.0

These four burials obviously display a significant diversion from “typical” corpse depositions known from Early Horizon cemeteries. It seems they were atypical burials, or so-called deviant burials. In this context it is normally understood that the burial form or style often depended (or might have depended) on the way that the dead person was perceived by the society in which they lived, or how they died and in what circumstances. It means that the fact that someone was buried in a way which diverted from the “regular” one reflected the way in which they lived, or who they were and how they died.

Applying this to the burials I describe, we could say that e.g. in the case of the second one, the 7-year-old child was buried in a grave which reflected the form and space of mother’s womb because the people who participated in the funerary ritual hoped the child would be “born” in “another life” in the same manner as he or she was born for the first time. Interestingly, the Sican Lord was buried in a similar way.

© W.Więckowski, under licence CC BY 4.0

When we interpret the burial of the adolescent, the third of the described graves, we could guess that the atypical form of the burial was connected with his/her physical appearance. We also know that in many pre-Hispanic cultures people with visible body defects were treated in a special way, as individuals “chosen” or “indicated” by gods. For instance, among the Incas (although it is indeed a very distant parallel), a person with a hump would be regarded as a child of the god of thunder Tunupa and predisposed to serve as a seer.

The disarticulated body of the man from the last atypical grave could be interpreted in many ways – as a body of “dismembered” human sacrifice, someone who was killed in a battle, or a body of someone who died far away from the planned burial location and their (incomplete) remains were transported to the resting place.

The adult buried in the first atypical grave might have been an acrobat. Some figurines (or usually figurine-shaped vessels) in the iconography of pre-Hispanic cultures represent acrobats performing similar feats.

© M.Giersz, under licence CC BY 4.0

The site of the Castillo de Huarmey is a constant source of surprise to us. It delivers exceptional finds, which feed our imagination and contribute to a better understanding of pre-Hispanic cultures, both preceding the Wari empire and those which came much, much later, of which I will tell you in another post.

You can read more about the discoveries and their interpretation in this paper:

Więckowski, Wiesław, Miłosz Giersz, and Roberto Pimentel Nita “The Hunchback, the Contortionist, the Man with the Stolen Identity, and the One Who Will Be Born in the Afterlife: Pre-Hispanic Deviant Burials from Huarmey Valley, Peru”, w: Tracy K. Betsinger, Amy B. Scott, and Anastasia Tsaliki (eds), The Odd, the Unusual, and the Strange: Bioarchaeological Explorations of Atypical Burials, Gainesville, FL, 2020, str. 152-169.

https://doi.org/10.5744/florida/9781683401032.003.0008

This article can be re-printed with photographs free of charge provided that the source is cited

Wiesław Więckowski – professor affiliated with the Chair of Archaeology of the Americas, University of Warsaw. He research is mainly associated with the project of exploration of the Castillo de Huarmey situated on the Peruvian coast. He also takes part in archaeological missions in Israel, most recently at the cemetery of Roman military camp Legio.

Edited by: J.C, S.A.

Cover: The group grave in the course of documentation. Stone architecture of the cemetery visible in the background, © W.Więckowski, under licence CC BY 4.0, ed. K.K.

This text was funded by the project entitled “Popularyzacja badań Katedry Archeologii Ameryk na Wydziale Archeologii”, a part of Inicjatywa Doskonałości – Uczelnia Badawcza program.