In the year 12 CE, a man named Harthotes submitted a census declaration to the local authorities in Roman Egypt. He was a 55-year-old farmer and local priest living with his elderly mother and young son in a house within the temple precinct of Theadelphia. But from other sources we knew that he also had a daughter named Tahaunes, who was about 12 years old at the time. Where was she? Not married off young, as scholars were quick to assume. The truth is more surprising: she was at work!

© W. G. Claytor CC BY-NC-SA 4.0 licence

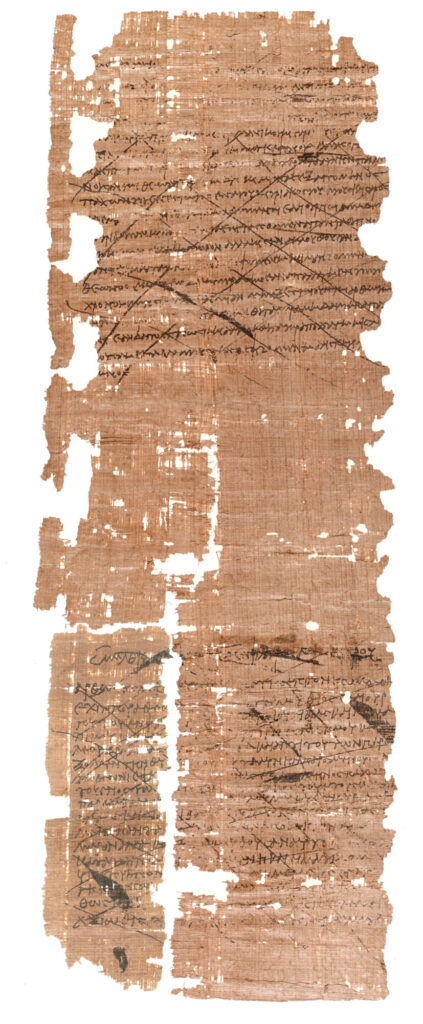

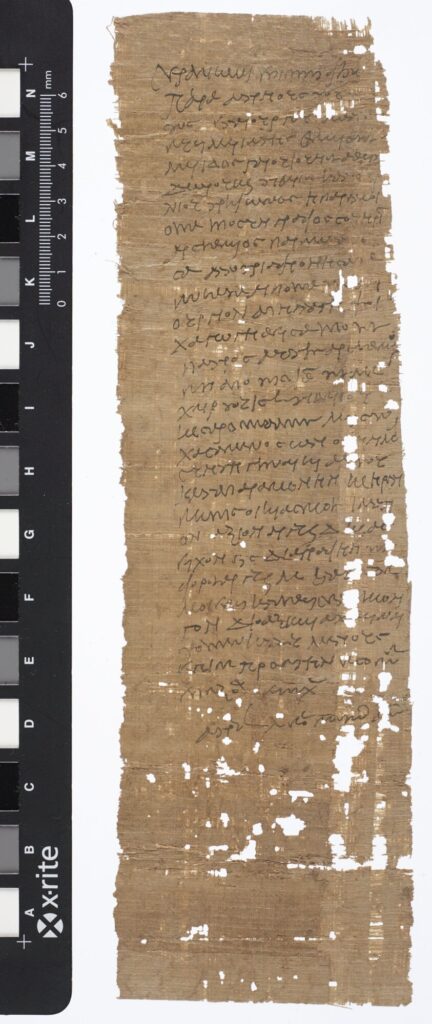

Her father had sent her out of the house to work at an oil mill in a village ten kilometers away, as we learn from two contracts preserved among the papers of Harthotes’ family. This group of papyri, about 50 in number and all in ancient Greek, was discovered clandestinely around 1920 in the ruins of the village of Theadelphia in Egypt’s Fayyum region. Today only the size of the site and a couple sturdy winepresses give a sense of its former importance, but a century ago the mudbrick housing quarters were still standing ruins. Perhaps the family’s documents were found amidst the rubbish of one of these houses, but the details of discovery are forever lost. Now dispersed over at least eight collections in Europe and the United States, the archive must be pieced together, bit by bit, in the hopes of restoring this valuable record of ancient peasant life.

Bentley Historical Library, HS11227, taken by Easton Kelsey, Spring, 1920

The main temple of the village was excavated by an Italian team in the 1930s and now serves as one of the highlights of the recently reopened Greco-Roman Museum in Alexandria. It was within the precinct of this temple that Harthotes lived with his family, but he was not a priest of the village’s main deity, Pnepheros (a form of the crocodile god Sobek), but rather of Tutu, a popular protective deity. As a priest of more minor god, Harthotes did not benefit from the privileges bestowed upon the other village priests, such as exemption from the poll tax. The annual demands of the Roman state for taxes and labor must have been a pressing concern for the family, which likely factored into Harthotes’ decision to send his young daughter out of the house to work.

© W. G. Claytor CC BY-NC-SA 4.0 licence

Working at the Press

The working arrangement was called paramone, a type of indenture common at the time. In the better-preserved contract, Harthotes received an advance payment of 80 drachmas in exchange for the labor of his daughter, who was to live and work under the roof of an oil maker for two-and-a-half years. A more fragmentary contract shows that this was the renewal of an earlier arrangement: in total, Tahaunes was at work for at least four-and-a-half years of her young life, beginning around age eight. Her employer was to feed and clothe her during her period of service, and Harthotes faced a fine of one drachma every day she was absent and stood liable for any misdeeds of his daughter, such as theft. Eighty drachmas was a significant sum, enough to feed the family for a few months or cover two years of Harthotes’ poll tax.

Image courtesy of the University of Michigan Library Digital Collections and the Columbia University Rare Book & Manuscript Library.

Tahaunes had to perform general service to her employer—she was a housekeeper of sorts—but also a particular task related to oil production denoted by the term paremballein, “to insert.” Archaeological evidence and modern ethnology help us better understand the particular task in question.

© W. G. Claytor CC BY-NC-SA 4.0 licence

After the harvest of fresh olives, there were two main steps to the production of oil, milling the olives into a paste, then pressing the paste to release the oil. To prepare for pressing, the paste needed to be placed into frails, a special type of basket called fiscinae by Roman agronomic writers and sphragides in Greek. The insertion of this paste into the frails, a messy, but delicate task well suited for small hands, is the step most suitably conveyed by the term paremballein. But of course Tahaunes may have assisted in other stages of oil production, such as the wearisome task of cleaning the mills and presses.

© W. G. Claytor CC BY-NC-SA 4.0 licence

Women and girls commonly performed such work, as we learn from a series of papyri outside the archive. They were called paremballousai, “(olive) feeders,” after their primary task. One contract stipulates that a woman is to be paid the same rate as the other paremballousai of the village.Another document, a petition from a village just down the canal from Theadelphia, tells us of a young paremballousa who was accused of running away from the mill with 40 drachmas and a cloak at the encouragement of her father. Theft and breach of contract! At least that was the view of the employer. The girl and her father must’ve thought otherwise: perhaps they considered the money and clothing due to them according to the terms of their agreement (Harthotes and Tahaunes would likely have agreed!). Together these documents offer remarkable insight into how girls and young women participated in the economy of Roman Egypt.

Image provided by The John Rylands Research Institute and Library, The University of Manchester

Gendered Labor

Ethnographic studies tell us that olive cultivation and oil production were often gendered operations divided along culturally specific lines. In the Kabyle culture of northern Algeria, for instance, women and girls have long performed key roles in the collection of olives and pressing process. An early 20th-century postcard illustrates the various roles of olive pressing in Kabylia, including a seated child who seems to have completed the task of filling the frails, although we must keep in mind that this staged photograph is a product of the colonial gaze that may have distorted actual practice. Nevertheless, the paremballousai of Roman Egypt clearly find a parallel in colonial Algeria. Reading across cultures can prove mutually enlightening, despite the wide span of time separating us from Tahaunes’ Egypt.

Image courtesy of https://www.mediastorehouse.co.uk/

Yet at least one contextual difference stands out between the work of Tahaunes and the girls and women of Kabylia. In Algeria, the work was performed within the family unit or what can be called the invisible economy of women’s work, which went “unnoticed, uncounted, and unacknowledged,” according to anthropologist Elizabeth Fernea. But the case of Tahaunes and Harthotes presents a very visible disposal of a daughter’s labor. Harthotes made this arrangement before a public notary, and it could have been no great secret back in Theadelphia that his daughter had been indentured to work for a man in another village. The labor of Tahaunes and many other female oil workers in Roman Egypt was done outside the family unit and under written contract, that is, it was very much part of the formal and acknowledged economy.

Kelsey Museum Archives 5.1576

Coming Home from the Mill

The case of Tahaunes, the girl at the oil mill, thus presents the possibility of making broad connections between the work of women and children across cultures, but also forces us to think carefully about specific contexts. Fortunately the papyri have preserved some of this context, allowing us to trace Tahaunes’ story within a multi-generational family archive. The family was in fact no stranger to indentured labor. Tahaunes’ uncle (Harthotes’ brother), for instance, had also been sent out of the house to work for four years. Importantly, we know that he came home, and so did Tahaunes, who married her cousin and had children of her own. Later, when Tahaunes was a grown woman, she accepted a loan of money secured by indentured labor, presumably performed by one of her sons. The family had thus come full circle.

© W. G. Claytor CC BY-NC-SA 4.0 licence

Such is the cyclicity of peasant life. Few could dream of the meteoric rise of the Makthar Harvester, who went from peasant to magistrate in late Roman North Africa, and fewer could accomplish it. No doubt Tahaunes and Harthotes were at least relieved when she finally came back from the olive press.

This article can be re-printed with photographs free of charge provided that the source is cited

Acknowledgements

This post was prepared in the context of the research project “Egyptian Peasants under Roman Rule: The Archive of Harthotes” financed by National Science Centre of Poland: Polonez BIS 1 grant (2021/43/P/HS3/00651). The research has been co-funded by Poland’s National Science Centre and the European Union’s Horizon 2020 Research and Innovation program under the Marie Skłodowska-Curie grant agreement no. 945339. Thanks are due to Tomasz Waliszewski for insight into the archaeology of oil production and to all my friends and colleagues in Egypt, including inspector Ahmed Hassan, who accompanied us during the recent International Winter School in the Papyrology and Archaeology of the Fayyum, funded by the IDUB program of the University of Warsaw and hosted by the Polish Centre of Mediterranean Archaeology, Cairo.

Author

W. Graham Claytor is a papyrologist and ancient historian at the University of Warsaw who specializes in family archives and notarial institutions in Greco-Roman Egypt.

Proofreading: S.A.

Editor: J.C.

Cover: ed. K.K.