The earliest large cities emerged in northern Mesopotamia during the Late Chalcolithic (c. 4200 – 2900 BCE). It was a time of transformation from local village-based social structures to big cities with hierarchical societies, more sophisticated division of labour and development of central authorities towards early states. The process of urbanization is well indicated by the rapid increase in settlement size, which at Tell Brak reached more than 120 hectares in mid-4th millennium BCE. It was however not clear whether this process was due to local population growth or migration and absorption of people from different areas. A recent bioarchaeological study published in the Journal of Anthropological Archaeology offered a new line of evidence, suggesting that the Late Chalcolithic urban growth was supported by migration. Much like today, people migrated into the city and settled in neighborhoods based around their shared migratory origins. These neighborhoods remained distinct communities that did not begin to integrate for multiple generations.

© Bertramz, published under CC BY 3.0, via Wikimedia

In a modern setting, the word urban makes us think of concrete jungles with sporadic green spaces, public transport, an abundance of 24/7 services and busy people looking for wifi. At first it might seem there is little left in common with ancient urban settlements, but the social processes that occur in both modern and ancient cities are not only comparable but relevant for the wider study of urbanization. As we move to an unprecedented era of human existence, with more than 55% of modern populations (and growing) residing in towns and cities, the past may help shape the future.

Public domain

The most universal feature clearly observable in all urban environments, past or present, are neighborhoods; they can either be pre-designed (managed from the top-down) or they can form organically (bottom-up) as the settlement grows. In either case, they form units within the larger settlement where social interactions take place and help alleviate the stress created by the increased interactions, referred to as energized crowding in social studies.

In Mesopotamia, home of the earliest large urban settlements, a great deal of variability has been noted in urban social organization. Abundant historical sources provide evidence of the establishment of special quarters for newcomers to cities across the region in the 3rd and 2nd millennium BCE, but how old was this practice? Can it be traced back to the beginning of urbanization as well, beyond our written records? In the absence of textual sources, archaeologists have instead studied neighborhoods by comparing architecture, infrastructure and material culture.

© A. Sołtysiak, CC BY-SA 4.0 licence

Tell Brak, located in the Syrian Khabur basin, is one of the best-known early urban sites with monumental architecture, long-distance trade networks and specialized craft production. At its apex, Brak covered over 120 hectares where the pre-existing and newly formed communities grew via migration from the surrounding satellite mounds towards the central mound, with migrants forming migrant communities or ‘neighborhoods’ in their new home. Excavations at Tell Brak have also uncovered human skeletal remains from multiple contexts, dating from the beginning of the Late Chalcolithic, the earliest phases of the local urbanization process, to the Early Bronze Age (c. 2900-2100 BCE). These gaves provided archaeologists an opportunity to study the remains of the very people who lived in these neighborhoods.

© A. Sołtysiak, CC BY-SA 4.0 licence

More and more, ancient DNA (aDNA) analysis has been utilized in the study of past populations, however this requires sample destruction and good preservation. Instead, visually observable features of the skeleton (phenotypic expressions) can be used as proxies for genetic data. Traits with high heritability rates become more common when people produce offspring with members of the same community. By measuring the frequency of multiple traits, it is possible to estimate the biological closeness of people not just within and between settlements, but also regionally or globally. Non-metric dental traits are one of the best features for estimating biological distance from appearance alone. These are hereditary features of teeth, visible to the naked eye, which can be systematically recorded. Because of their high (98%) mineral content, teeth are generally well-represented in archaeological contexts. The dental data was recorded using the Arizona State University Dental Anthropology System (ASUDAS) and then analyzed using various statistical techniques, such as Euclidean distances, Gower coefficients and Mean Measure of Divergence, explained in detail in Maaranen et al (2022).

© A. Sołtysiak, CC BY-SA 4.0 licence

Analysis of the teeth from Tell Brak supports the archaeological findings. Site archaeology suggests that the early Late Chalcolithic population growth was driven by immigration from nearby communities, which depopulated the surrounding region in a 4 km radius. When these people settled in Tell Brak, they did so in the same communities (i.e., villages), reflecting a phenomenon observed in modern cities as well, like the contemporary Chinatown in Los Angeles or the many ethnic communities that sprang up in New York City during the early twentieth century. These findings indicate that the development of migrant neighborhoods is likely as old as the process of urbanization itself.

© A. Sołtysiak, CC BY-SA 4.0 licence

The separation of the Late Chalcolithic groups at Tell Brak and the later similarity between the Late Chalcolithic and Early Bronze Age offers insights into the broader evolution of cities. Tell Brak, like many early Mesopotamian cities, was mostly organic in formation growing through inward migration toward the city and its satellite mounds. In the end of the 5th millennium BCE extensive structural changes took place as both religious and secular buildings were erected on the main mound, while middens and industry shifted to the surrounding mounds. The rapid growth of the city likely influenced these changes that suggest a more centralized governance and culture. While the formation of migration-based neighborhoods may have started organically, it is possible they became part of a more centralized system with increased integration to alleviate the pressures caused by the rapid population growth.

© A. Sołtysiak, CC BY-SA 4.0 licence

After its initial migration wave, there were no major disruptions in the population structure of Tell Brak in the Late Chalcolithic. Even the emergence of the Southern Mesopotamian Uruk culture in the mid-4th millennium BCE did not cause notable changes; They controlled a vast trade network with colonies across Western Asia from southern Anatolia to Iran. Despite this, the Tell Brak population remained stable with some segments of the Late Chalcolithic population continuing to reside there until at least the end of the 3rd millennium BCE. With time, the Tell Brak neighborhoods (satellite mounds) became integrated with the communities in the larger mound which is evidenced by the decreasing differences between dental trait variation in the different sub-samples.

Authors:

Nina Maaranen is a Finnish archaeologist specialised in human osteology and the eastern Mediterranean, particularly the Levantine region during the Bronze Age. She is currently affiliated with the Archaeology departments at the University of Sheffield (teaching technician and collections curator) and Bournemouth University (visiting research fellow).

Jessica Walker is a bioarcheologist and Assistant Professor at the Northeast College of Health Sciences in New York, USA. She has worked on projects examining human skeletal remains and explored questions related to archaeological populations in the Near East, Southern Urals, and throughout the United States. Currently, she teaches courses in human anatomy and pathophysiology.

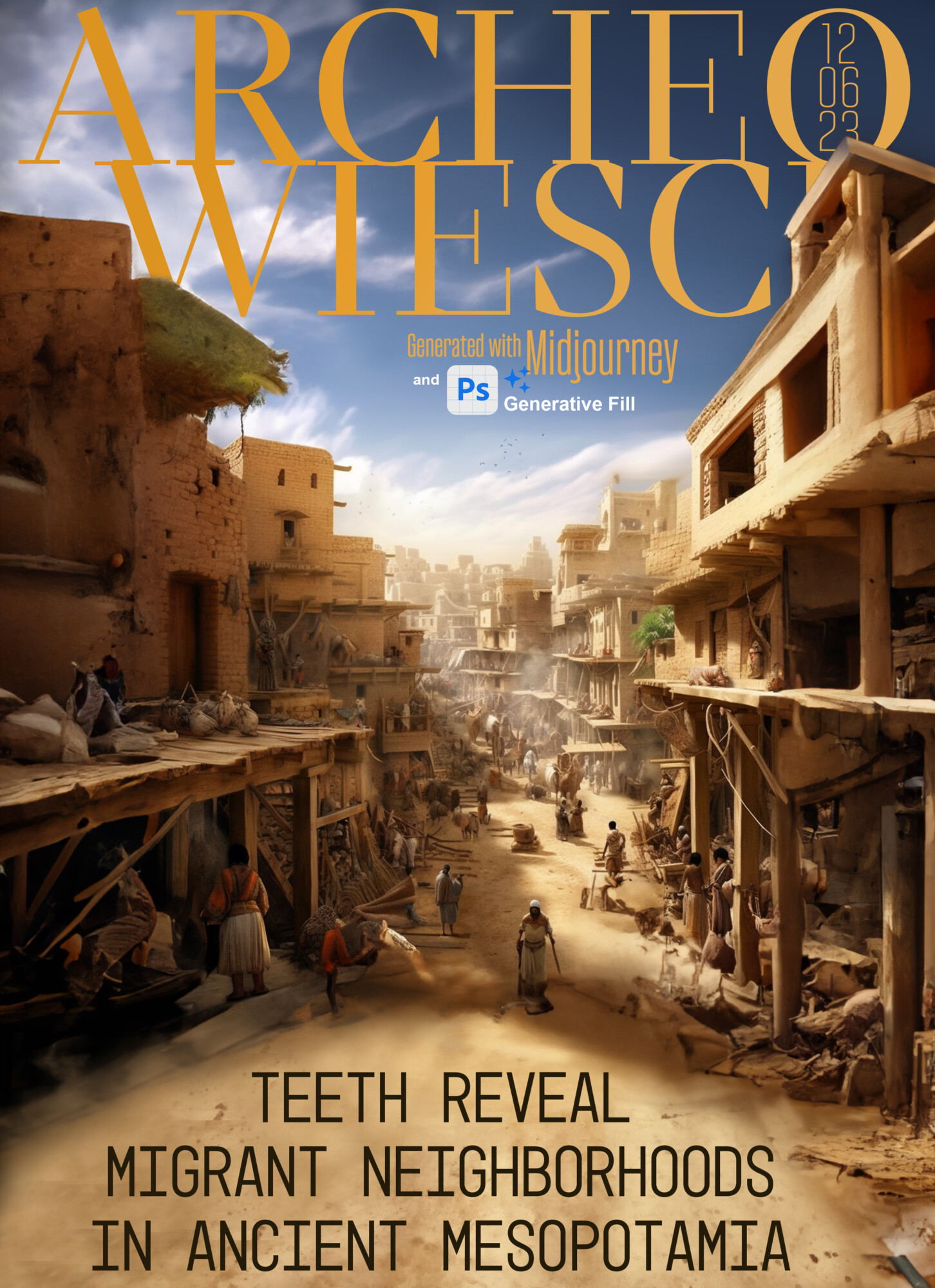

Cover: Illustration generated in Midjourney with the use of PS Generative Fill, edit Archeowiesci

Promt: generate inside look of city life in a ancient city Tell Brak from 3000 B.C.E period

It sounds logical that the lion’s share of the city growth relied on immigration from the surroundings and that the newcomers would settle in the neighborhoods formed by people of the same origin. It is unclear why villagers would abandon their natural habitat and move to conglomerates. If for the sake of security, then how to explain that the pristine cities were unfortified. If for the sake of economic security, what were the benefits?