Cremation is one of the most common types of burial rites practiced by various communities around the world. Nevertheless, the first associations that spring to mind for these practices, during which the remains of the deceased were consumed by fire, would lead us in the direction of the Vikings or the inhabitants of much of Northern Europe during the Late Bronze Age or Iron Age. In this case, however, a doctoral student at the University of Warsaw and editor of Archeowieści will tell the story of a particular area of western Mexico where, more than six centuries ago, cremation was the main funeral rite for at least a part of the Indigenous community. Burials associated with the local community of this region were recently discovered in the Middle Balsas River valley, which constitutes the border between the states of Michoacán and Guerrero. Traces of these funerary practices are the subject of a remarkably important study conducted by the author in collaboration with researchers from the Instituto Nacional de Antropología e Historia Michoacán and Universidad Nacional Autónoma de México, under the direction of Dr. José Luis Punzo Díaz.

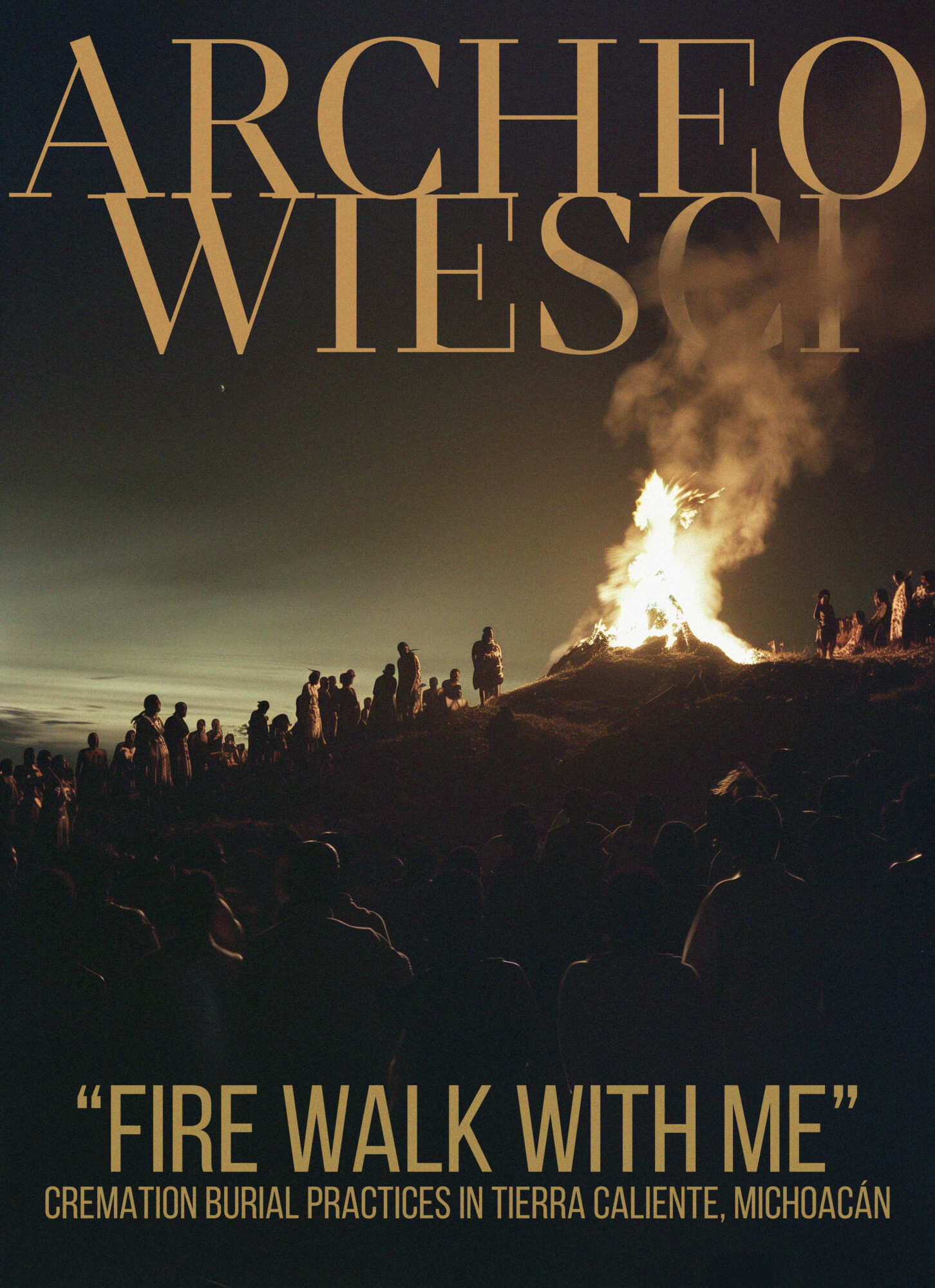

“Fire walk with me”

As a member of the editorial team of Archeowieści, so far I have had the pleasure of preparing and editing multiple popular science posts about the intriguing and fascinating studies and publications of other researchers. Here, however, I finally have an opportunity to present my own research. The area from which the burials that are the subject of the following story come is considered to be troubled and dangerous. Nonetheless, it is inhabited by societies that also express a unique level of care for and dedication towards their local heritage, both culturally and archaeologically. It was under these unusual circumstances that I came to carry out research on the curious phenomenon of the cremation of the dead from more than 600 years ago.

I would like to invite you to read the preliminary results of a study on cremation burial rites from the Balsas River Valley region, which was recently published in the journal “Ancient Mesoamerica”. Further considerations of specific behaviors during funerary rites will also be published in “Latin American Antiquity“. But perhaps I’ll cover this another time….

Michoacán: place of the fishermen

The Postclassic period, the span of time between 900 and 1530 AD, is the best-recognized pre-Columbian epoch in the western part of Mexico. However, in the case of

Michoacán, this statement is only really accurate in terms of the central part of the state. Since the beginning of the 13th century, the land of the present-day State of Michoacán was dominated by the rule of kings from the eagle dynasty (Uacusecha), who made their mark on history as the Tarascans. They ruled over a multiethnic Empire, with their capital and heart of the kingdom located at Tzintzuntzan, on the shores of lake Pátzcuaro. The famous Great Platform is probably the most recognizable and emblematic construction in the whole domain of the Tarascans. It consists of five distinctive pyramids called yácatas, each of which were dedicated to the deities protecting the kings of the Uacusecha dynasty. However, distinctive Tarascan pyramids were also erected in other important urban centers of the empire. Excavations, led by José Luis Punzo Díaz, are currently taking place in Tzintzuntzan. They will certainly bring many exciting new discoveries in the coming years that will allow us to better understand the history of this spectacular urban center.

The Tarascan are also known to have been the arch nemesis of their more famous neighbors: the Aztecs. These two societies formed the two largest Postclassical empires in Mesoamerica and were locked in a constant struggle for dominance. Possibly the most important battle was that fought at Taximaroa (now Ciudad Hidalgo). In 1478, the King of the Aztecs, Axayácatl, at the head of an army consisting of circa 32,000 warriors, raided and plundered a few of the border cities. After these short-lived and minor victories, the invaders were crushed on the outskirts of Taximaroa by a 50,000-strong Tarascan army led by King Tzitzic Pandacuare. Based on oral traditions, at least 20,000 Aztec warriors died in the battle…

© A. Budziszewski, under licence CC BY-NC-SA 4.0

The legend and legacy of the Tarascans is of great importance for many people in Michoacán today. Moreover, the most numerous Indigenous society, the Purépecha people, consider the creators of this empire to be their direct ancestors. For all the inhabitants of Michoacán, the past glory of the Uacusecha is a source of pride and a symbol of their independence and distinctiveness from the rest of the republic.

As I mentioned earlier, the western part of Mexico is still inhabited by numerous Indigenous societies, which use various languages from distinct language families. The early colonial writings about the region of Tierra Caliente and/or the Middle Balsas region mention the native societies utilizing the Nahuatl, Otomi and Matlatzinca languages. This applies to the later part of the 16th century, and the diversity of the linguistic and ethnic mosaic in the era before the Spanish conquest period may have been even more complex. According to the investigators from INAH Michoacán, the cemetery from which the burials I examined come was in use in the period even before the conquest of Tierra Caliente by the Tarascans, which most likely occurred in the second half of the 15th century. Therefore, it seems correct to conclude that in the cemeteries of Los Tamarindos the remains of their dead were deposited by members of the local, pre-Tarascan community. Naming a specific ethnos at this stage of research is impossible. And it might be unachievable…

© A. Budziszewski, under licence CC BY-NC-SA 4.0

Tierra Caliente, meaning the hot lands

© alaznegonzalez, under licence CC BY-SA 3.0

The region called Tierra Caliente extends from the border between the states of Jalisco and Michoacán, to the western part of the State of Mexico and Guerrero. This geological basin is formed by the valleys and catchment areas of two rivers, the Tepalcatepec and Balsas, and is surrounded by the mountain ranges of highland Michoacán. Due to these conditions, Tierra Caliente stands out from the rest of its neighboring lands, geologically and naturally, but also culturally. The region is characterized by low annual precipitation and high temperatures, often exceeding 40℃ and sometimes reaching as high as 50℃! Currently, Tierra Caliente makes its way to the front pages of newspapers mainly in connection with crime, especially narcotráfico. However, this part of the republic is also known for its phenomenal cuisine, which is hallmarked by the overwhelming authenticity and variety of flavors on offer. Perfectly balanced spices dominated by chili and salt enhance the grilled and dried meats drizzled with lemon juice, accompanied by homemade corn tortillas along with the obligatory bottle of Coca-Cola (or cold-chilled Corona, Pacifico, or Victoria beer). And for the most courageous, Tierra Caliente offers grilled iguana accompanied by fresh vegetables, beans, and flavorful salsa. This part of Mexico is also known for its captivating instrumental music with a distinctive sound called son calentano.

© A. Budziszewski, under licence CC BY-NC-SA 4.0

It was in this area, near the town of Huetamo, in 2015 that researchers from INAH Michoacán, led by Dr. José Luis Punzo Díaz, discovered the Los Tamarindos cemetery, which I have the pleasure of investigating.

Cremation in the heart of Tierra Caliente

A total of 42 cremation burials were discovered in an area of about 30 m². Urns with burnt human bone fragments were placed side by side on a level volcanic geological horizon characteristic of Michoacán and referred to by the term tepatete. Due to that, this burial ground has a form similar to the European urn fields, characteristic for the (nomen omen) Urnfield culture.

The burned human remains were found within the ceramic containers. Therefore, the participants of the several-hour-long ceremony, during which the bodies of the dead were transformed under the influence of fire, had to wait a few more hours. For what purpose? So that bone fragments could be collected from the remnants of the funeral pyre, without the risk of being burned by the still glowing and smoldering remains of the pyre.

Meticulous examination of the funerary urn and the analysis of the archaeological material allowed me to determine that the bodies of the deceased were decorated with seashell and, in one case, obsidian blades, as well as singular beads made of animal bone and limestone. Most of these artifacts originally formed beautiful jewelry such as necklaces, pendants, or ornaments for wrists or ankles. These kinds of grave goods are known (and better preserved) from other archaeological sites in the Middle Balsas region. Thanks to these finds, we can imagine how the body of the deceased was dressed before the cremation. Except for these pyre goods, I also found multiple copper bells deposited within the funerary urns. Metal objects were also deposited outside the burials, especially in one particular offering (?) pit, where someone had deposited copper rings, an anthropomorphic figurine, and… human molars…

Metallurgy in West Mexico

West Mexico is the birthplace and location of the most dynamic development of metallurgy in Mesoamerica. The valley of the Balsas river is especially abundant in copper ores. The aforementioned copper bells crafted in this part of Mesoamerica in the Postclassic period were a true fashion sensation. In addition, researchers have suggested they also had immense ritual significance. The sound of multiple bells could resemble the melody of rainfall or roll of thunder, and as a result they may have been used in fertility rituals… Nevertheless, these metallurgic masterpieces are not only found in nearly all corners of Mesoamerica, but they also reached as far north as the territories of the present-day states of Arizona and New Mexico!

This is no mere flight of fancy. In fact, interdisciplinary analyses have shown that these distant bells were smelted from copper ores from the Balsas River Valley! Thus, they were not fakes or copies made somewhere along the way, but original creations from West Mexico. Does this mean that among the dead buried at Los Tamarindos are also the copper masters themselves? This would be particularly hard to confirm scientifically. However, in the scant accounts dating back to the first decades after the Spanish Conquest, chroniclers from Europe visiting Tierra Caliente mention a number of myths related to local guardian deities of metallurgy. Based on that, some researchers have suggested that this could have had a ritual and religious impact on the cremation burial rites. In my opinion, definite confirmation of both hypotheses would be insanely difficult to achieve. However, in a popular science text, we can allow ourselves one or two scientific fantasies. 😉

What can burned bones possibly tell us?

Thanks to the detailed analysis of the bones, I was able to determine that both children and adults, of both biological sexes, were cremated. The youngest cremated individual died between the age of one and two! Just determining how many of the dead were buried in a cremation burial is extremely difficult. After all, each of the thousands of bone fragments could theoretically have come from the remains of a different person. However, in the case of most child burials, it seems to me that each urn was prepared specifically for one person.

© A. Budziszewski, under licence CC BY-NC-SA 4.0

Analysis of the remains allowed me to make more observations. The structure, color, and deformation that the bones undergo as a result of the fire indicate what conditions prevailed during the cremation. I am referring in particular to the temperature of the pyre. Although we are unable to estimate it in terms of degrees Celsius, the color and brittle structure of the burnt bones indicate that the temperature of the pyre most likely did not exceed 900℃. Other circumstances during the cremation that may have had a similar impact on the remains should also be considered, such as low combustion efficiency or short burning time. The latter possibility would suggest that there may have been interference with the funeral pyre while the cremation was still in progress. Spectrometric analyses may be helpful in solving this mystery, which I hope to use in the future.

Computed tomography in the service of archaeology

Thanks to colleagues from INAH and Universidad Nacional Autónoma de México (UNAM) who scanned the urns using computed tomography, I was able to virtually look into the urns before starting the examination process. Moreover, this technology allows us to investigate the spatial distribution of the material over and over again.

In addition, it was possible to determine that the hard volcanic soil covering the funerary urns pushed the burnt bones to the very bottom of the vessel. This was due to the urns being covered with soil in the cemetery. As a result, the pressure of the earth gradually destroyed the covers and crushed the remains and grave offerings placed in the urns. Moreover, many burials were later additionally affected by tree roots, which further disturbed the original arrangement of the remains in the urns.

Fortunately, in the case of one burial belonging to an adult male, the situation was very different. The urn was damaged, but only the lower part of the vessel was broken. By securing the urn with an elastic bandage, it was possible to maintain the original arrangement of the remains in the grave. While working on this burial, I quickly noticed that the remains of the deceased had been collected from the pyre and arranged in a very precise manner. The upper part of the vessel was dominated by the bones of the skull, which gradually gave way to the bones of the lower limbs. This allows us to conclude that the remains from the pyre were collected consistently —- starting with the head and ending with the legs (or vice versa) — and that the body was placed in an upright position. Otherwise, the mourners would not have been able to collect and “reconstruct” the deceased in such an accurate manner as I observed several hundred years after the burial.

© A. Budziszewski, udner licence CC BY-NC-SA 4.0

To be continued…

In the coming months, I hope to present the results of further analysis and shed light on other aspects of this fascinating burial rite. For more scientific details about my research on cremation burials in the central Balsas River valley, please see my article published in the “Ancient Mesoamerica” journal.

This article can be reprinted free of charge, with photos, and with the source indicated

Author: Adam Budziszewski

Proofreading: S.A.

More literature about Michoacán, Tierra Caliente, and Los Tamarindos:

Alcalá J. (2019) [ca. 1541] La Relación de Michoacán, El Colegio de Michoacán.

Beekman C.S. (2010) Recent Research in Western Mexican Archaeology, „Journal of Archaeological Research”, 18 (1), 41–109. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10814-009-9034-x

Borbolla D.F. (1948) Arqueologia Tarasca, (w:) 4ta Reunión de Mesa Redonda: El Occidente de México, Museo Nacional de Historia, Sociedad Mexicana de Antropología, 29–33.

Brand D.D. (1943) Recent Archaeologic and Geographic Investigations in the Basin of the Rio Balsas, Guerrero and Michoacan, (w:) 27a Congreso Internacional de Americanistas, t. 1, 140–147.

Budziszewski A. (2023) A preliminary bioarchaeological study of the funerary urns from Los Tamarindos, Tierra Caliente, in Michoacan, Mexico, „Ancient Mesoamerica”, 1–20. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0956536123000184

Gastelum-Strozzi A., Peláez-Ballestas I., Cue Castro A., Rodriguez P., Dena E., López Trujano R. & Punzo-Díaz J.L. (2019) Non-invasive Morphological Studies of a Tomographic Dataset of Funerary Urns from the Middle Balsas Region in Michoacán, Mexico, „Journal of Archaeological Science: Reports 28. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jasrep.2019.102053

González y González L. (2001) Introducción: La Tierra Caliente, (w:) J.E. Zarate Hernandez (red.) La Tierra Caliente de Michoacan, El Colegio de Michoacán. https://www.biblio.com/book/tierra-caliente-michoacan-zarate-hernandez-jose/d/1015546029

Hosler D. (1994) The Sounds and Colors of Power: The Sacred Metallurgical Technology of Ancient West Mexico, MIT Press.

Lister R.H. (1947) Archaeology of the Middle Rio Balsas Basin, Mexico, „American Antiquity” 13 (1), 67–78.

Lumholtz C. (1903) Unknown Mexico: A Record of Five Years’ Exploration Among the Tribes of the Western Sierra Madre, Rio Grande Press.

Meighan C.W. (1974) Prehistory of West Mexico, „Science” 184 (4143), 1254–1261

Plancarte F. (1893) Archeologic Explorations in Michoacan, Mexico, „American Anthropologist” 6 (1), 79–84

Pollard H.P. (1993) Taríacuri’s legacy: The prehispanic Tarascan state, University of Oklahoma Press.

Pollard H.P. (1997) Recent research in West Mexican archaeology, „Journal of Archaeological Research” 5 (4), 345–384. https://doi.org/10.1007/BF02229257

Punzo Díaz J.L., Ibarra Ávila E.T., Zarco Navarro J. & Castañón Suárez, M.A. (2020) Revisiting the Archaeology of the Huetamo Area, Southeastern Michoacán, Mexico, (w:) J.D. Englehardt (red.), Ancient West Mexico, University Press of Florida, 103-130

Williams E. (2020) Ancient West Mexico in the Mesoamerican Ecumene, Archaeopress Publishing Ltd. https://doi.org/10.2307/j.ctvwh8fmq

Cover: Illustration generated in Midjourney, edited by K.K.