The Shomu-Shulaveri Neolithic culture, located in the heart of the Transcaucasian region, continues to captivate researchers. This prehistoric phenomenon, which spans the territories of Georgia, Armenia, and Azerbaijan, is distinguished by its unique local characteristics. While much research has focused on communities in Armenia and Azerbaijan, settlements in Georgia, particularly Khrami Didi Gora – the largest of them all, remain mostly unexplored. Known for their agricultural and craftsmanship skills, the people of this society also appear to have had profound spiritual beliefs, as evidenced by the small anthropomorphic figurines discovered at this archaeological site. However, what did these beliefs entail? How did rituals shape their daily life and worldview? These lingering questions continue to challenge researchers, awaiting answers that may unlock the mysteries of the people belonging to this fascinating archaeological culture.

© 2023 by Mariam Tsukhishvili, published under CC BY-NC 4.0

Unveiling the Shomu-Shulaveri Culture

The last excavation at Khrami Didi Gora, one of Georgia’s largest Neolithic sites, took place forty years ago. Now, young archaeologist Mariam Eloshvili is leading the charge to uncover new insights from this prehistoric site, breathing new life into its excavation. Khrami Didi Gora is part of the Shomu-Shulaveri culture, a significant Neolithic community that thrived along the Kura River Valley in what is now Georgia, Armenia, and Azerbaijan. Dating back to the early sixth millennium BC, the Shomu-Shulaveri culture is regarded as the most important in the Transcaucasian region. It is sometimes referred to as the Aratashen-Shulaveri-Shomu culture, a name that reflects the wide geographical span of its influence.

The first discovery of this culture was made by Ideal Narimanov at the site of Shomu Tepe in western Azerbaijan between 1958 and 1964. Soon after, archaeologists Aleksandre Dzhavakhishvili and Tariel Chubinishvili uncovered similar settlements in Georgia, namely Shulaveri Gora. These sites shared many cultural characteristics such as circular houses, stone and bone tools, ceramics, and the use of obsidian.

One of the most fascinating aspects of the Shomu-Shulaveri culture is its very origin. While some scholars point to the influence of Mesopotamia’s Hassuna and Halaf cultures, others suggest that the cultures of northern Iran and the Zagros Mountains played a key role. This is supported by similarities in stone and bone tool usage and pottery styles and burial type such as cremation (Aruchlo), yet no definitive conclusions have been reached.

© 1982 by Georgian National Museum, published under CC BY-NC 4.0

Secrets of Khrami Didi Gora

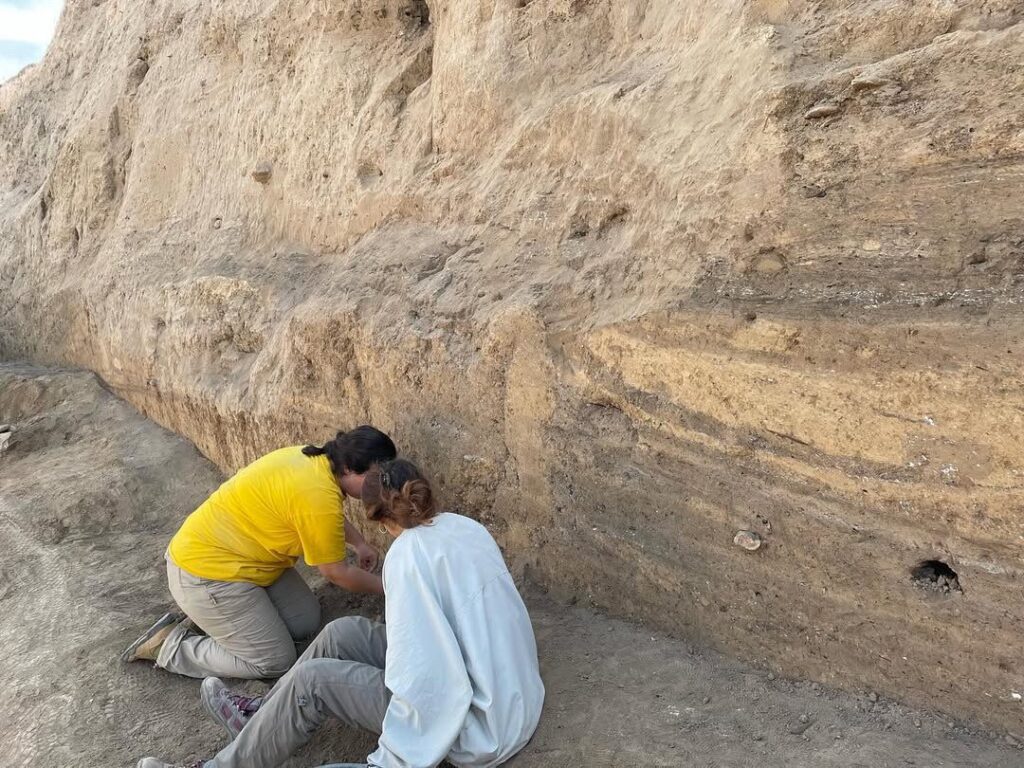

Found in Georgia’s Kura Basin, the archaeological site of Khrami Didi Gora, dated to the sixth millennium BC, is the largest Late Neolithic settlement, covering 4.5 hectares. Archaeological excavations first took place between 1972 and 1982 (Photo 1), only to be revived in 2023, opening a new chapter in its exploration (Photo 2).

The settlement consists of circular houses of varying diameters made from mud brick. Evidence from the site suggests central postholes in several buildings, indicating possible roof support structures. Architecturally, Khrami Didi Gora shares the closest similarities with Imiris Gora (Georgia) and Mentesh Tepe (Azerbaijan).

Recent excavations have yielded an abundance of remarkable objects, such as stone and bone tools, ceramic fragments, and grinding stones. While much of the recent focus has been on cleaning and preserving finds, earlier excavations uncovered a wide variety of materials—clay, stone, and bone—highlighting the settlement’s complexity.

© 2023 by Megi Vacheishvili, published under CC BY-NC 4.0

Burials from Khrami Didi Gora – a mystery still awaiting discovery

Neolithic burials are rare in the Southern Caucasus, with only four previously discovered: Aknashen in Armenia, Kamiltepe and Mentesh Tepe in Azerbaijan, and Aruchlo in Georgia. Among these, the Aruchlo burial is particularly significant as it contains cremation remains, evidence of an extremely rare practice in Transcaucasia’s Neolithic period. Although burials are a well-documented feature of this cultural sphere, Khrami Didi Gora stands out for the absence of any known graves, a mystery still awaiting discovery.

Cultural significance

The site has yielded a wide range of artifacts from both past and recent excavations. Among these are several bone tools that served various purposes, including farming, pottery-making, textile and leather production, as well as wood or stone processing. Artifacts include bone tools such as scrapers, bone prickers, chisels, fibulas, hammers, cutting-edge tools and polished implements along with other household objects, including grinding stones, stone vessels, and stone axes. Additionally, the site has produced various rough-molded ceramics with relief ornamentations, as well as fine pottery. The site also contains numerous tools made of flint and obsidian. Furthermore, a variety of anthropomorphic figurines and animal remains have been discovered, suggesting both symbolic and practical significance within the culture.

Following the clues of shark bones

Notably, the research in Khrami Didi Gora has yielded various bone tools, including those made from antler and… shark bone. The latter material, also discovered in Armenia, Azerbaijan, and Georgia, is believed to originate from the Black Sea Catran shark. However, further research is needed to confirm this identification. The discovery of shark bone is particularly intriguing, as it suggests potential trade or cultural exchanges with distant coastal regions, despite the site’s inland location. This underscores the significance of trade and interaction in the prehistoric world, indicating that these early societies were likely engaged in long-distance networks.

Ritual significance of the settlement

Archaeologists excavating Khrami Didi Gora have discovered that the site is not only notable for its socioeconomic connections, but also for its rich evidence of rituals. Several buildings and artifacts revealed relics of intriguing rituals. However, a major research question remains: what beliefs did the people hold, what ceremonial behaviors did they exactly practice, and how did religion influence their daily lives? The following key findings shed light on possible answers.

© Giorgi Javakhishvili, 2015, published under CC BY-NC 4.0

Building 30 – a key ritual structure

Building 30 stands out among other structures at the site. It has an irregular, round shape, resembling Ritual Buildings 9 and 10 at Imiris Gora in Georgia. Unique objects found here further suggest its ritual importance. Among the most significant discoveries are anthropomorphic statues – 17 of them in total – most of which are broken, but still reconstructable. These statues typically represent seated female figures, which implies their association with a fertility cult. They are even referred to as seated figures of the “Big Mother” cult. These figurines have small pointed heads with holes where eyes may have been inserted, suggesting the use of different materials for their implementation. Most of them lack hands, but feature pointed breasts and massive lower limbs that are fused together. Made of unbaked, mixed clay, these statues range in height from 4 to 6 cm. They offer valuable insights into the community’s spiritual and cultural practices.

© Giorgi Javakhishvili, 2015, published under CC BY-NC 4.0

© Giorgi Javakhishvili, 2015, published under CC BY-NC 4.0

Unique figurines from other buildings

Along with the traditional female figures, other unique figurines were found in Building 31/36, especially in Hearth 53. Among them, A well-preserved female figurine with realistic features, including rounded eyes, brows, a small mouth, a pointed head, and breasts (Photo 6). Another figurine found in the same building is damaged, with a broken body and head, but still displaying rounded eyes and mouth. This figurine also has black paint on the head and neck area and presents features that are hard to interpret in terms of presented sex. Its unusual cylindrical-conical shape, with a backward-inclined head, is unlike other figures at the site or in the surrounding region.

© Giorgi Javakhishvili, 2015, published under CC BY-NC 4.0

Additionally, another figurine, this time from Hearth 55, has a similar facial design but with a spherical body shape, that suggests the figure might be wearing clothing, as the lower limbs are not pointed. This piece is also ornamented around the neck and head area.

© Giorgi Javakhishvili, 2015, published under CC BY-NC 4.0

© Giorgi Javakhishvili, 2015, published under CC BY-NC 4.0

Other fascinating discoveries

Other intriguing finds include a female figurine with a pierced shoulder, which may have been intended for use as a hanging wall-like ornament or charm. Another small head-shaped figurine was found, but its body was broken at the neck, preventing full reconstruction. Its facial features include small holes for the mouth and eyes, and the head has a pointed tip, suggesting it may have been adorned with a hat. Traces of white paint found near the eyes and black dots may represent facial tattoos, though this remains a hypothesis.

© Giorgi Javakhishvili, 2015, published under CC BY-NC 4.0

The role of religion and spirituality

The discovery of a large number of seated female anthropomorphic figurines reinforces the theory that religion and spirituality were central to the lives of the Khrami Didi Gora community. These artifacts most likely represented fertility and divine protection, providing a deeper understanding of the prehistoric beliefs and rituals.

Building 34 – a ritual centre

Another significant building is Building 34, which measures 4 meters in diameter. At its centre is an oval-shaped clay hearth unlike the others in the area, as it shows evidence of intense fire. The eastern portion of the building bears significant fire traces, suggesting that this was not a domestic structure but was instead used for rituals. Beneath the eastern wall, pottery containing animal (pig?) bones were discovered. This building is connected to Building 33 via an interior wall. The latter also exhibits a distinct fire odour, further indicating its use for ritualistic purposes. Notably, Wall 41 in this area contains a bull head with horns on a pedestal, similar to discoveries at the Çatalhöyük archeological site, where a bull head was presumably hanged on a wall.

© 2023, Ana Davitashvili, published under licensed under CC BY-NC 4.0

Interdisciplinary challenges and ongoing research

For archaeologists working at Khrami Didi Gora, collaborating with experts from other disciplines is essential to understand the ritual context of the settlement and the broader prehistoric communities that laid the foundation for urbanization and agriculture in the South Caucasus. The ongoing research aims to provide insight into the Shulaveri-Shomu Tepe culture, a complex phenomenon that remains partially understood. Although various archeological sites related to this society have been investigated, many issues concerning their lifestyle and origins remain unanswered. Key questions still include the origins of the Shulaveri-Shomu people, their influences from the Near Eastern traditions, and the role of religion in their everyday lives.

© 2023 Mariam Eloshvili, published under licensed under CC BY-NC 4.0

More specifically, the researchers also wonder what evidence supports the presence of hierarchical societies within this culture, and how were economic and social activities organised? Were these managed by elites? Furthermore, how did the Shulaveri-Shomu Tepe people create and spread technological knowledge throughout the region, and how much did they affect surrounding cultures? What was the significance of agriculture in this society, and how did they manage crop cultivation and animal husbandry? These questions remain vital for understanding their lifestyle and the spread of their innovations to other neighboring communities.

Moving forward – challenges and prospects

While there are many opportunities for archaeological study within the Shomu-Shulaveri culture, several challenges remain. Thus, understanding the social structures, agricultural methods, and regional connections will be crucial for shedding light on its role in the development of early agricultural communities in the South Caucasus and beyond.

© 2023 Megi Vacheishvili, published under CC BY-NC 4.0

By refining the chronological framework, investigating social organisation, and considering agricultural techniques or regional interconnections, we can finally gain a clearer understanding of the Shomu-Shulaveri culture and its lasting influence on later cultures.

© 2023 Mariam Eloshvili, published under CC BY-NC 4.0

Authors:

Ana Davitashvili is a PhD student at the University of Warsaw, specializing in bioarchaeology. Her research focuses on stable isotopic analysis of human, animal bones and plant remains, with particular emphasis on understanding ancient diets and husbandry practices. Her work is centered on the Neolithic transition period, exploring how shifts in subsistence strategies may have influenced social and cultural developments.

ResearchGate: https://www.researchgate.net/profile/Ana-Davitashvili-3

Orcid: https://orcid.org/0009-0005-7903-7715

Mariam Eloshvili – PhD candidate, Ilia State University. Mariam graduated MA from University of Warsaw in 2021. From 2023, she is a PhD candidate in archaeology at Iliauni. She is interested in the Neolithisation processes of the Caucasus and the Near East. Her PhD research is focused on Khramis Didi Gora, and her main aim and question is an examination of the socio-economic and cultural aspects of the Neolithic societies. Mariam’s PhD research is supported by the Rustaveli National Foundation.

ResearchGate: https://www.researchgate.net/profile/Mariam-Eloshvili

Academia: https://iliauni.academia.edu/MariamEloshvili

Project on Facebook: https://www.facebook.com/profile.php?id=100093249527069

Project on X: https://x.com/Khrami_s_Gora

This article can be re-printed with photographs free of charge provided that the source is cited

References:

Glont, l., Javakhishvili, A., Kiguradze, T. 1975. Kvemo kartlis arkeologiuri ekspeditsiis mushaobis shedegebi (1972-1973). (Archaeological survey reports from Kvemo Kartli 1972-1973) Sakartvelos sakhelmtsipo muzeumis arkeologiuri ekspediciis shedegebi, Metsniereba IV, pp. 22-37.

Japaridze, O., Javakhishvili, A. 1971. Udzvelesi Mitsatmokmedi mosakhleobis kultura Sakartvelos teritoriebze [First agricultural societies on the territory of Georgia], SSR Georgia, pp. 37-107.

Javakhishvili, G. 2015. Adamianis Gmosakhuleba sakartvelos udzvelesi khanis plastikashi (neolitis khanidan feodaluri khanamde); [Human form in Ancient Georgian plastic art], pp. 13-41.

Menabde, M., Kiguradze, T., Kikodze, Z. 1978, Kvemo kartlis arkeologiuri ekspeditsiis mushaobis shedegebi ( 1976-1977); [Archaeological survey reports from Kvemo Kartli 1976-1977], Sakartvelos sakhelmtsipo muzeumis arkeologiuri ekspediciis shedegebi, Metsniereba VI, pp. 27-47.

Editor: A.B.

Cover: